On my sister‘s advice, I went to go see Ballets Russes yesterday evening at the Film Forum, and she was right: It’s a stunning film, one that I’d even recommend to people who have little-to-no interest in ballet. Like the best documentaries — and this is the best I’ve seen in some time — Ballets Russes transcends its immediate topic to capture larger and more ephemeral truths. The movie not only brings to life a bygone era in the arts and helps to explain the current popularity of ballet in the US and around the world — it also powerfully reflects on both the inexorable passing of time and the timelessness of dance, its magical capacity to wash away years and overcome human frailty. Like a perfectly executed ensemble piece, Ballets Russes can take your breath away.

On my sister‘s advice, I went to go see Ballets Russes yesterday evening at the Film Forum, and she was right: It’s a stunning film, one that I’d even recommend to people who have little-to-no interest in ballet. Like the best documentaries — and this is the best I’ve seen in some time — Ballets Russes transcends its immediate topic to capture larger and more ephemeral truths. The movie not only brings to life a bygone era in the arts and helps to explain the current popularity of ballet in the US and around the world — it also powerfully reflects on both the inexorable passing of time and the timelessness of dance, its magical capacity to wash away years and overcome human frailty. Like a perfectly executed ensemble piece, Ballets Russes can take your breath away.

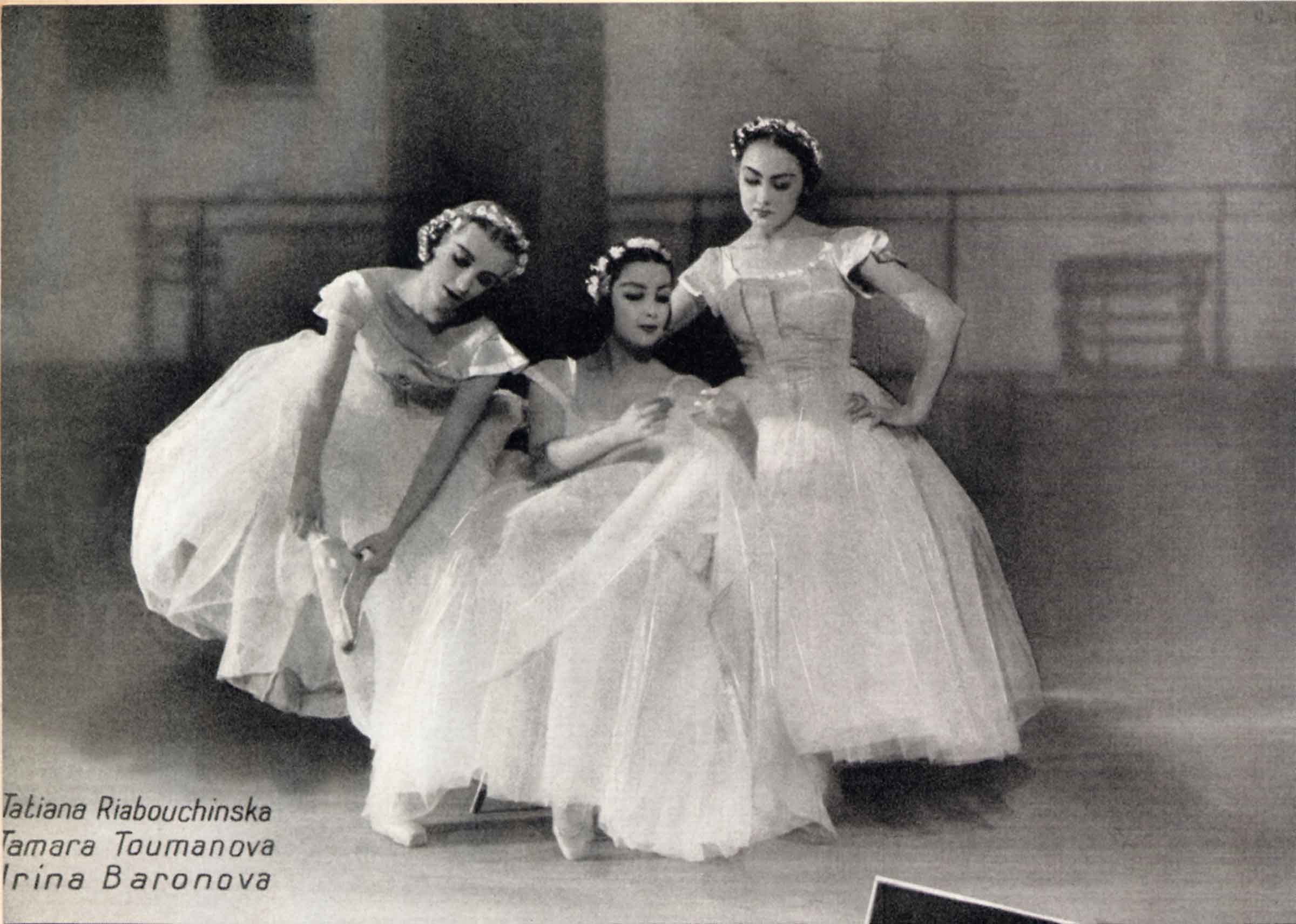

After a brief introduction to the dancers of the Ballets Russes, who reconvene in New Orleans in 2000, the documentary shifts to 1929, with the death of renowned ballet impresario Serge Diaghilev and the formation of the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo, a successor company to Diaghilev’s famed troupe. Briefly artistic-directed by a young George Balanchine (who’ll show up again in the story, after a stint training elephants at the circus) and headlined by a trio of newly-discovered Russian “baby ballerinas,” the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo soon splits into rival companies — one headed by dancer-choreographer Leonide Massine, the other manned by financial backer Colonel Wassily de Basil. After wrangling over ballerinas and staffing their respective companies with ringers from other ensembles, the two Ballets Russes duel over London audiences and US contracts, until the exigencies of World War II force both to travel West. There, they attempt to stave off financial collapse by spreading the ballet meme (via steam train and Hollywood song-and-dance) across the New World.

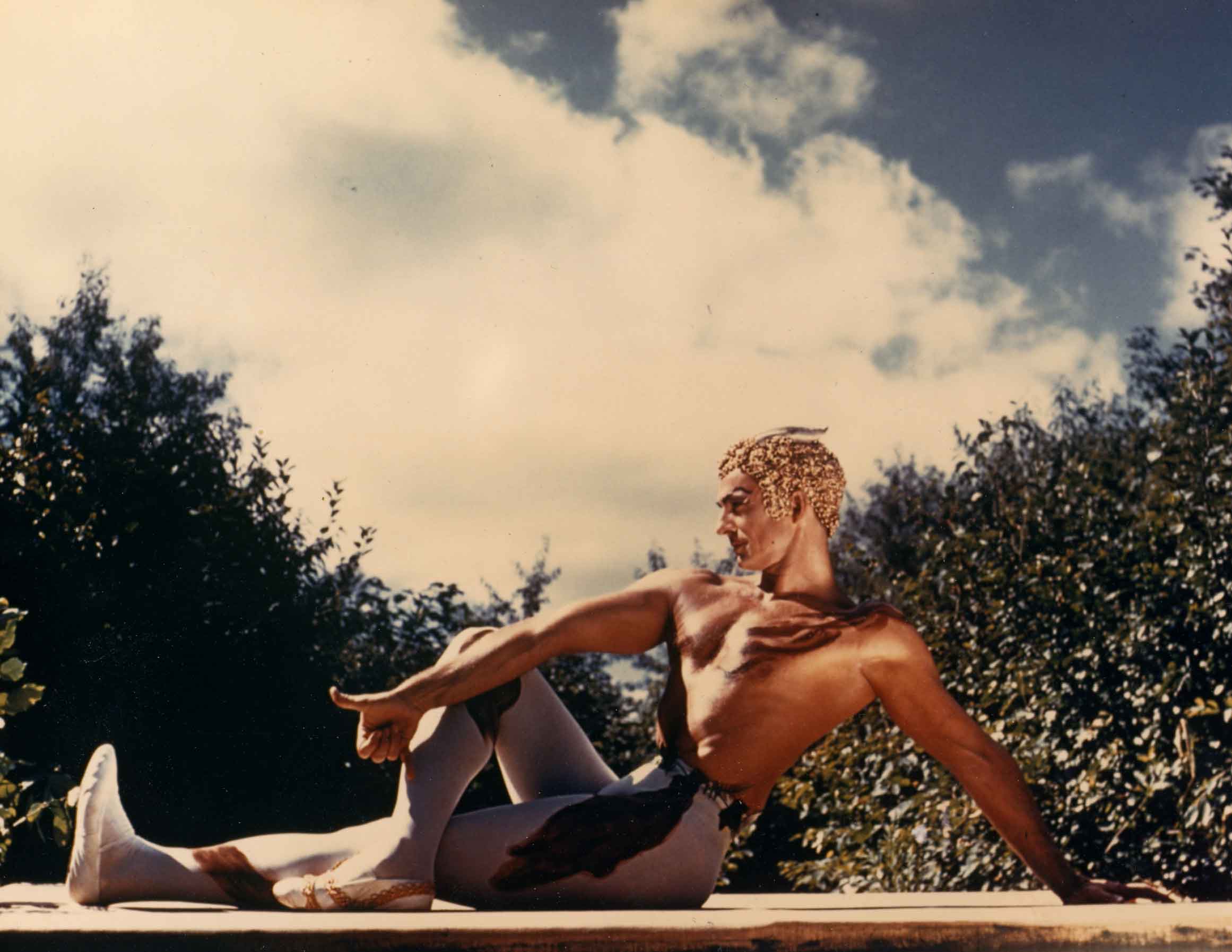

The story of the Ballets Russes is told not only through an impressive amount of archival dance footage (which loses none of its forcefulness despite the occasional grainy stock), but also via interviews with the surviving dancers of the rival troupes, and herein lies the documentary’s considerable dramatic heft. Every single one of the many interviewees — which include Alicia Markova, Maria Tallchief, and Frederic Franklin (who still appears in ABT’s “Swan Lake” well into his nineties) — comes off as a vivacious, multifaceted personality with tales to tell, and it’s extraordinary to watch them shake off the years when speaking of their experiences or dancing. Former ballerina (and coquettish heartbreaker) Nathalie Krassovska — who, like several of the participants, passed away since the film was finished — lights up like a little girl when she shows off her dance studio. Later, she and George Zoritch (in his prime at right, now an eighty-something gym rat in Tuscon, AZ) attempt a pas de deux from Giselle, and, although it’s clearly a physical struggle, it’s endearing to watch them rejoice in their old, shared language.

And the same goes for many other participants in the film, who have spread across the globe in a ballet diaspora since the collapse of the company in 1962. Aged, wizened faces break into impish grins when an old memory surfaces, and, when these former stars show off a dance flourish to their students, it’s exhilarating to see their enthusiasm, and the flashes of grace that accompany it. In all honesty, I’d like to have heard more about the original Ballet Russes here (Diaghilev’s outfit), and the film loses focus somewhat in the fifties and sixties. (More of a general sense of history would’ve been nice, too — The Depression isn’t mentioned, Hitler and WWII seem to show up out of the blue, and, other than a fascinating aside involving black dancer Raven Wilkinson’s travails with the KKK during one of the Ballet Russes’ southern swings, there’s very little outside context here.) Nevertheless, Ballets Russes is an amazing documentary and an impressive testament to the idea that, while dancers come and go, the dance is forever, and to embrace it as a calling is a life well lived.