In writing a favorable review of

The Prestige in 2006, I compared Chris Nolan’s film version of

Christopher Priest’s novel to an expertly-crafted, well-wound clock: “

a dark, clever, and elegant contraption…that suggests razor-sharp clockwork gears and threatening pulses of electrical current, all impressively encased in burnished Victorian-era mahogany.” Well, the watchmaker is at it again: Audacious, trippy, inventive, and maybe a touch too sleek in the end,

Christopher Nolan’s Inception is a psychic heist film that’s easily among the best mainstream releases of 2010. While

Toy Story 3 actually packed more of an emotional punch, this is one fun night out alright, and as smart and engaging a summer sci-fi action flick as we’ve seen since last year’s

District 9.

Now, to be clear: Like Nolan’s The Dark Knight and its obviously rushed third act, I have some definite issues with the movie, which I will get into a moment. But, also like TDK, these issues don’t really detract from the actual viewing experience as it unfolds. So, if you want to consider the last few paragraphs here as mainly nitpicking to death an otherwise entertaining and more-clever-than-we-probably-deserve summer movie experience, you’re within your rights. The upshot is: You should definitely see it yourself and come to your own conclusions — Inception is worth the ten bucks and then some.

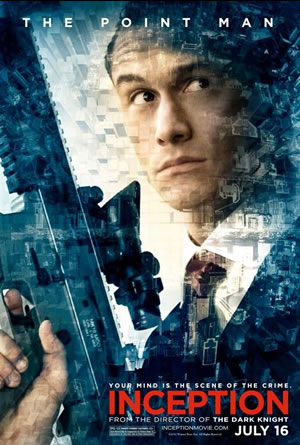

Inception was originally billed by Nolan back in 2009 as a “contemporary sci-fi actioner set within the architecture of the mind,” and, short of The Romantic’s “Talking in Your Sleep,” that’s as simple a way of describing the plot as any. Here, Leonardo Di Caprio’s Dom Cobb is a corporate security specialist who — along with his right-hand man Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt, burnishing his cool) and his “Architect” (Lukas Haas, Team Brick assemble!) — spends his days hacking important intel from people’s heads by manipulating their dreams. This futuristic process is called “Extraction,” and Dom and his team are very, very good at it, but not so good that a job doesn’t get botched now and again…partly because Cobb happens to carry along some unwieldy subconscious baggage, in the form of the often-armed, always-disarming Mal (Marion Cotillard).

On the hook with a very powerful individual (Ken Watanabe) after one of these jobs gone awry, the Dream Team are presented with a counter-offer — one that, if successful, will mean Cobb gets the diplomatic immunity he desperately desires to go home and see his kids again: Plant an idea deep in the head of a corporate rival (Cillian Murphy) and hope it will germinate — a process known as “inception.” Now, this is a more complicated affair than the business-as-usual of extraction, because, apparently, people’s brains reject memes that they perceive as coming from somewhere else. (I take it Nolan has never met a Glenn Beck viewer.)

And so, as per men-on-a-mission movies from The Magnificent 7 to Ocean’s 11, Cobb goes out to recruit a bigger, better team for this heist — including a “forger” (Tom Hardy) to play-act the needed characters in the mark’s brain, a “chemist” (Dileep Rao) to handle the tricky sedation situation, and a more enterprising Architect (Ellen Page) to build a more labyrinthine mousetrap of a dream. But even as this expanded collection of expert psychonauts prepares for the Big Score, there’s still the matter of that alluring French skeleton in Cobb’s psychic closet. And the more the new Architect — Ariadne by name — unearths the secrets within Cobb’s troubled brow, the less she wants to spend any time sharing a dreamscape with these damaged goods…

The fact that Ellen Page’s character is un-self-consciously called Ariadne should give you a sense of how occasionally clunky Inception can be in the early-to-middle-going, when Nolan’s characters are forced to explain the basic rules of the game — extraction, inception, “projections” and “totems” and the like — in expository bursts. Now, on one hand, I’m guessing most fans of science fiction generally have a high tolerance for this sort of please-explain-your-terms speechifying anyway. (Otherwise, so many sci-fi tomes couldn’t start along the lines of: “While flipping idly through the Vidquik transmids from Cathedral space, Dren Garrit settled his XLV-Class Starfarer into a cruising altitude of 26 parsecrons over Koggoth,” etc. etc.)

That being said, some of the ground-rules here do seem rather arbitrary, others seem undeveloped (what was that business with the basement opium den?), and others seem to change as the story progresses. (Most obviously, the midpoint introduction of Limbo. Speaking of which, 1) Why would Murphy’s deepest dream at the end be set in the di Caprio-Cotillard version of Limbo? and 2) how did Leo and Saito get out of their dream at the end without a clap?) But the wall-of-text exposition scenes are one of my smaller quibbles with Inception. After all, the rules are the rules — so long as they’re followed once they’re established, I don’t have too much trouble with this sort of thing. (And as an aside, wasn’t it nice of Martin Scorsese to make the Limbo-set prequel of Inception, earlier this year?)

A bigger problem, to my mind, is that, for a movie about dreams, Inception seems a little too wary not to draw outside the lines. When I brought up the watchmaker metaphor at the beginning, it’s because, at times, this feels like a Bond movie conceived and written by Dr. Manhattan — brilliant in its complexity and ingenuity alright, but maybe just a little too perfect for human purposes, and even a bit…cold. (“I would only agree that a symbolic clock is as nourishing to the intellect as photograph of oxygen to a drowning man.“) FWIW, and for whatever reason, I found the (m)Orpheus and Eurydice side of the story much more emotionally resonant than Cobb’s rather hackneyed quest to see his kids’ faces again. (I mean, c’mon now, really?)

What do I mean by “too perfect”? Well, I tend to find my dreams both more innocuous and more flat-out-bizarre than anything going on in Inception. Like, I don’t really tend to dream that I’m an extra in In Her Majesty’s Secret Service. I tend to dream I’m at work in my cubicle, except my old kitchen is attached, and I have on blue facepaint and Berkeley‘s there, only he’s wearing an Abe Lincoln stovepipe hat, and my co-workers are trying to feed him a talking goldfish but I think that’s a bad idea, and Elvis Costello and Ray Davies are in the corner doing a mean cover of “Waterloo Sunset,” except it sounds more like Lady Gaga and it’s way too long for a 3-minute speech anyway… (Freudians and Jungians stand down. I just made this example up, and has nothing to do with my real dreams…as far as you know.)

The point being, dreams, even or especially the throwaway ones, are usually weird. But the Bondian vignettes in Inception just seem like video game levels to me. (Level I: Grand Theft Auto, Level 2: The Matrix, Level 3: Modern Warfare 2.) This relative aridness of Nolan’s Dreaming is compounded by the generic thug baddies all about — I don’t know about you, but I kinda think some of my dream projections would have super-powers or really scary reptile fangs or something — and by the fact that Nolan goes out of his way to explain every single thing about these dreamscapes, to the point where the actual ragged, twisted-pretzel logic of dreaming gets lost in the shuffle.

One of the bravura sequences in the film (also referenced heavily in the trailers and in my anticipatory post, so not a huge spoiler) is @hitRECordjoe‘s Matrix-y solo mission in the gravity-free hotel. And, yet, there’s a very specific story reason why JGL is floating around here. A cool story reason, to be sure, and the way different dreamworlds overlap with snap-into-place logical precision is one of the more satisfying aspects of the film. But, in dreams, does everything really have to have a reason? Shouldn’t he just be able to float, like, when he wants to, or just because he is?

Again, don’t get me wrong — I know much of the back-half of this post is my leveling fanboy complaints towards an intelligent, well-realized, and very fun summer movie. I enjoyed myself quite a bit during Inception, and I’ll very likely see it again. Still, like any number of dreams, both the movie’s logic and its captivating power do look a little more threadbare upon reflection after the fact. Twas a good dream, but a dream nonetheless.