Five armies, seventh Doctor? The cast for Peter Jackson’s The Hobbit fills out further with Sylvester McCoy (Radagast the Brown), Ken Stott (Balin), Mikael Persbrandt (Beorn), Ryan Gage (Drogo Baggins), Jed Brophy (Nori), William Kircher (Bifur), and, back for more, Cate Blanchett as Galadriel. [Earlier casting here.] Very glad to see this moving along.

Category: Cinema

Danse Macabre.

Well, I was rooting for Darren Aronofosky’s Black Swan. I generally think well of Aronofsky even if The Wrestler notwithstanding, he has a penchant for operatic self-indulgence. (In the Best of the Decade list I put together a year ago, The Fountain, The Wrestler, and Requiem for a Dream clocked in at #77, #35, and #30 respectively.)

And, at least in general terms, the subject matter of Black Swan hits close to home, given that my sis is a professional ballerina who’s well-versed in the Odette/Odile role(s). (Although, as far as I tell, she hasn’t gone off-the-wall, certifiably bugnuts crazy…yet. Gill’s thoughts on Black Swan are here.) All that being said, Aronofsky’s attempted Cronenberg variation on Tchaikovsky here doesn’t really work. The movie is arousing a good bit of passion and controversy at the moment — some critics love it, some hate it, there may even be an age divide — but, for the most part I just found it overwrought and silly.

Black Swan begins auspiciously with the prologue of the ballet from which it’s riffing: Young dancer Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman) dreams she’s on stage performing the opening “transformation sequence” of Swan Lake, when Odette first encounters the villainous sorcerer Von Rothbart. (Here and throughout, Portman doesn’t really have the ballet chops to pull off the dancing, but, to my layperson’s eye, the workarounds seemed decently convincing. And she’s actually quite good otherwise.) But outside of the Dreaming, Nina is still just a lower-level dancer (presumably a soloist) in her Lincoln Center-based company, living with her (s)mother (Barbara Hershey) in a too-small New York apartment.

But opportunity knocks for Nina when the company director (Vincent Cassel, seemingly playing himself) tires of his veteran principal (Winona Ryder) and decides to recast Swan Lake from the ground up. (And for some reason, he only seems to be picking one cast.) Nina seems like a perfect fit to dance the willowy, innocent Odette, the White Swan. But can she handle the Black Swan half of the equation: the alluring temptress Odile? In fact, there’s a carefree, sensuous new corps member — with swan wing tattoos, no less (Mila Kunis) — that seems born to play that role. So if Nina wants to live her dream and dance the lead in this new Swan Lake, she has to cut loose from her perfectionist moorings and embrace her dark side. Which, unfortunately for her, brings on the Madness…the Madness, splitting in half…

Thus ensues a series of increasingly nightmarish vignettes, in which Nina — already fragile and anorexic on her best days — succumbs to teh crazy: Mirrors start acting funny, a stress rash grows worse and worse, and soon she’s ripping long strips of flesh off her fingers at the cuticle. (I wasn’t kidding when I said this was a Cronenberg variation, although the “all-in-a-day’s-work” body horrors of The Wrestler also come to mind.) Unfortunately, while Black Swan pretends to be a psychological horror movie, most of the scares here are really just of the jump-scare or gross-out variety. And, other then an ecstasy-fueled nightclub scene that recalls the druggy cinematic syntax of Requiem (and that eventually devolves into a ludicrous “sapphic succubus” tryst that seems like something out of Showgirls), Black Swan spends too much of its run dancing dangerously on the precipice of boring.

The thing is: If we know the lead character is going bonkers, and that’s made pretty clear from jump street, these endless nightmare sequences have very little dramatic weight to them. Something bad happened, somebody got killed? Eh, she’s probably just imagining it. What might’ve made Black Swan more interesting is to emphasize not how she’s going mad, but why. But, in that department, Aronofsky mostly just burdens Nina with trite Freudian baggage — an overbearing mother and a sexy crush on “father” (a.k.a. Cassel) — that was hoary and cliched even in Tchiakovsky’s day.

And so it’s hard to sympathize with Nina because neither her character nor her plight is at all convincing. So she has to somehow play both an innocent AND a seductress? ZOMG how will she ever manage? Well, I dunno, how about…acting? Sure, there are cases where Method types will lose themselves too much in a part. (Heath Ledger’s travails with the Joker come to mind.) But, perhaps due to familiarity with ballet folk, playing the white and black swans just doesn’t seem like an insanity-inducing event to me. (Although, now that I think about it, I guess a psychotic break after portraying evil twins might explain the late career path of the Shat.)

In the Financial Times, dance critic Apollinaire Scherr makes a key and telling point: In emphasizing the psychological rigors of the Black Swan role, Aronofsky sorta missed the point of the ballet. “Sure, there is a good maiden and a sly vixen in Swan Lake, but, like the ballet’s dopey prince, Aronofsky gets them mixed up. The virtuous woman has a self to lose; the schemer merely fakes it. Odile the Black Swan is easy to understand…what you see is what you get…Odette – part swan, whole queen, once simply a woman – is complex: wild but also majestic, animal yet gentle.”

In other words, the White Swan is the character with actual depth, while the Black Swan is basically all sizzle and flash, the prince falling for a pretty face. In that, the movie Black Swan is much like its namesake. I suppose it works decently well as a cheesy midnight movie for goth girls and the like. But in terms of anything approaching tragic or psychological depth, Black Swan misses the mark wildly. Its pleasures and pains barely scratch the surface.

Cackling into the Night.

“‘The idea is to use these fragments of cut scenes and use CGI to have The Joker appear one last time,’ a source explained. ‘Chris wants some continuity between movies and for the franchise to pay tribute to Heath and his portrayal of the Joker.‘”

Take for what it worth, but a New Zealand paper is reporting that Chris Nolan will give Heath Ledger’s Joker one final bow at some point in The Dark Knight Rises. “‘It would only be a fleeting moment in the movie and would only be included with the full consent of Heath’s family,’ the source added.” Perhaps an after-the-final-credits flourish? Update: Or not. “‘That’s all wrong,’ said the writer-director.“

The Clown and the Ringmaster.

“‘I am serious,’ Nielsen replies. ‘And don’t call me Shirley.’ The line was probably his most famous — and a perfect distillation of his career.” First dramatic, then comic actor Leslie Nielsen, 1926-2010. (See also Matt Zoller Seitz’s appreciation.)

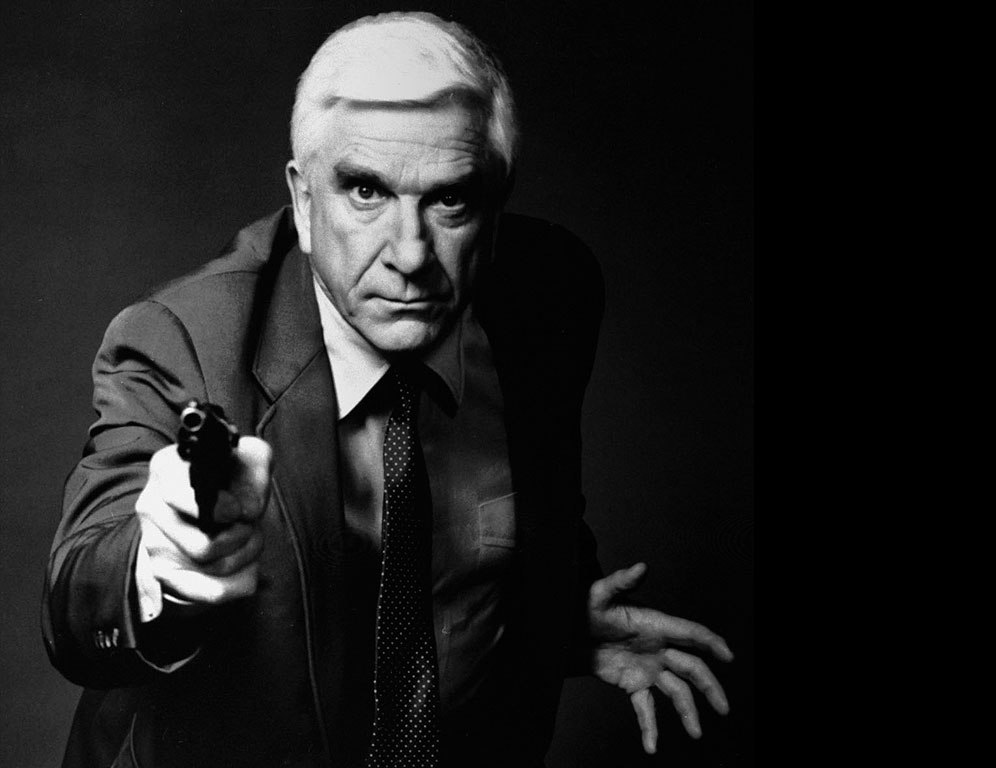

“I’d say he was probably the most successful versatile director in Hollywood. He could do just about anything really well, from science fiction to cult thrillers to domestic dramas to westerns to romantic comedies.” To, of course, Star Wars films. Director Irvin Kershner, 1923-2010. (The great Kershner pic above via Quint at AICN.)

Nowhere is Safe.

When reading the seventh and final Harry Potter tome in 2007, my sense was it felt more like a scriptment than a novel, and, tho’ often clunky as a book, it would probably work better as a movie a few years down the road. And, hey, I was right! (At least so far.) Even though it’s only half the story, and the leisurely camping half at that, David Yates’ Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix Part I is easily one of the best films in the series — perhaps the best, if you prefer your Potter relentlessly dark. (I know Cuaron’s Azkhaban has a following, but for me the real competition is Mike Newell’s Goblet of Fire.)

A hardy veteran of Dumbledore’s army at this point — this is his third Potter film in a row after Order of the Phoenix and the Half-Blood Prince — Yates has taken the often-unwieldy wanderings of the first half of Hallows and fashioned a lean, tense, and gripping fugitive story out of them. Better yet, he’s brought a much more palpable sense of danger and darkness to the proceedings. When I read the book, I missed Hogwarts most of the time and wondered why our heroes had to spend so much time camping. Here, the lack of Hogwarts goes unnoticed, and it’s abundantly clear why Harry, Ron, and Hermione spend so much time on the lam — They’re totally under the gun…er, wand.

That may be the part that rankles some of the youngest viewers out there, or their parents — From the creepier-than-usual Warner Brothers card on, the gloom here is unrelenting, and almost sadistic. Hallows begins with a Great Eye — that of the Minster of Magic (Bill Nighy), who’s making a Churchillian attempt to rally the wizarding world against the encroaching forces of Voldemort. (Good luck with that.) The Dark Lord (Ralph Fiennes), meanwhile, is entertaining his Death Eater shock-troops with a banquet at the Malfoys — one punctuated by the torture and eventual murder of Hogwarts’ Professor of Muggle Studies. She dies pleading for clemency from her former colleague, Severus Snape. (Clearly, she was new to academe.)

The Big Three are no happier. Harry (Daniel Radcliffe) is packing up and hiding the Dursleys somewhere safe from harm — It’s gotten so bad that he’s even nostalgic about his old room under the stairs. Hermione (Emma Watson) has resorted to wiping her Muggle parents’ minds of her existence. And Ron (Rupert Grint)…well, ok, like his older brothers, Ron is still a bit of a goof (at least until his arm almost gets ripped off in a freak disapparating accident later on.) And this, Ron’s injury notwithstanding, is all before Mad-Eye Moody (Brendan Gleeson) shows up at 4 Privet Drive with an army of returning cast members — or, as anyone who’s read the book knows, cannon fodder.

Granted, these supporting characters aren’t exactly Redshirts — we know most of them from the first six movies. Still, here is one of the situations where, to my mind, the movie rubs up against the limitations of the source material. There’s a line in Red Letter Media’s worthy evisceration of The Phantom Menace where the narrator makes the very valid point: “Qui-Gon Jinn and Obi-Wan Kenobi should have been combined into one character named…Obi-Wan Kenobi.” The same goes for the Potterverse.

By here in Book 7, several thousand pages into the tale of young Mr. Potter, the story is now totally crufted over with narrative stuff. Dozens of characters are running around already, and yet Hallows seems to pile on more every time our heroes get in a jam. (For example, Harry gets a tip from an old journalist friend of Dumbledores, whom we’ve never met, to go visit an old historian friend of Dumbledore’s, whom we’ve never met. Couldn’t one of these just have been Jim Broadbent’s Slughorn, from Book Six?)

We’re equally overstuffed here with magical Maguffins — Seven horcruxes and three hallows, not to mention three gifts from Dumbledore and various other wonderful toys, like Harry’s watchful mirror, Hermione’s infinite knapsack, and a steady supply of Polyjuice Potion. With so many magical items in play, the ground rules get fuzzy, and the sense of danger takes a hit. (Then again, they’re fuzzy anyway — Where can and can’t House elfs go again? And why aren’t our team using that highly convenient Room of Requirement from Book 5 to solve all of their problems?)

Still, one definite bright side of having so many populating the Potterverse is that the series continues to be a welcome full-employment program for British thespians. Bill Nighy and Rhys Ifans (as Xenophilius Lovegood, Luna’s dad) are the most prominent additions to the cast, but there are other fun faces joining the party this time, including David O’Hara (Braveheart) as Harry’s face in the Ministry, Guy Henry (Extras, Rome‘s Cassius) as Voldemort’s puppet minister, and Peter Mullan (Children of Men, Red Riding) as the Death Eater head of security.

On this front, the series is now an embarrassment of riches. When the likes of John Hurt and Miranda Richardson have all of fifteen seconds of screen time, and even the House elves are voiced by names like Simon McBurney (The Last King of Scotland, The Ghost Writer,) and Toby Jones (as Kreacher and Dobby respectively), you know you’ve got a heck of a cast on your ends. And the three kids have grown up to be no slouches in this department either. I can’t tell if they’re great actors, but they’re definitely very good at being Harry, Ron, and Hermione at this point.

So, in the end and despite its narrative over-packing, Deathly Hallows is an entertaining and scary ride with some very memorable setpieces. There’s an animated sequence late in the film that’s as beautiful and entrancing as anything we’ve seen in all seven movies thus far. And I was also fond of Harry, Ron, and Hermione’s assault on the Ministry, packed as it was sly allusions to Terry Gilliam’s Brazil. (Note the big statue, the gaggle of hangers-on breezing by, and Mullan being a man consumed with paperwork.) There’s still a lot of camping here, sure, but at least this time it feels less like aimless meandering and more like an urgent necessity. Let’s hope Yates and co. can land this magical bird in as fun a fashion next July.

Story Matters on A(TV)C.

“All in all, these AMC series remind me of American movies made in the early-to-mid-’60s, when Puritanical content restrictions were starting to break down and commercial films were embracing a new frankness, but filmmakers hadn’t yet gone into the ‘anything goes’ mode that dominated the final quarter of the 20th century…[A]s mid-’60s American film demonstrated, there’s more than one way to be ‘adult.’ AMC seems to have realized this and embraced it, and it’s one of the reasons the channel is flourishing.”

Salon‘s Matt Zoller Seitz (formerly of The House Next Door), sings the praises of AMC, home to Mad Men, Breaking Bad, The Walking Dead and Rubicon. I watch all of those except Rubicon, which is still languishing on the DVR for the time being. (Now that it’s canceled, unfortunately, I may never get around to uncorking it. This was also the fate of Carnivale.) As for The Walking Dead, it’s seriously overwritten at times — the sisterly pow-wow about fishing at the top of Episode 4 was just embarrassing — but I’ll stick around through the first season at least.

Countess Dracula Sleeps.

The bats have left the bell tower. The victims have been bled, red velvet lines the black box. Actress (The Wicker Man, Doctor Who), blogger, Den of Geek columnist, and seminal Hammer horror siren Ingrid Pitt is dead, 1937-2010. “She was partly responsible for ushering in a bold and brazen era of sexually explicitly horror films in the 1970s, but that should not denigrate her abilities…All fans of Hammer and of British horror are going to miss her terribly.“

Fragments of Legacy Code.

“I kept dreaming of a world I thought I’d never see. And then, one day, I got in.” The Daft Punk guys release snippets of their upcoming Tron: Legacy score. I have a feeling there’s no way this film can live up to the hype, but these eleven minutes sound pretty darned good.

Crime of the Century.

A tale of two financial crimes: After the Savings and Loan Crisis of the late 80’s and early 90’s — a clear consequence of Reagan-era deregulation, by the way — had run its course, 1852 S&L officials were prosecuted, and 1072 of them ended up behind bars, as did over 2500 bankers for S&L-related crimes. But, when a similarly-deregulated Wall Street plunged the US economy into a much steeper recession two decades later…nobody (with the notable exception of Bernie Madoff) went to jail — In fact, it was barely even admitted by the powers-that-be that serious crimes had even occurred at all. So what happened?

That is the stark question driving Charles Ferguson’s well-laid-out prosecutorial brief Inside Job, which works to explain exactly how we ended up in the most calamitous economic straits since the 1930s. If you’ve been keeping up on current events at all, even if by comic books, stick figures, or Oliver Stone flicks, then you won’t be surprised by the frustrating tale Inside Job has to tell. But unlke the more inchoate and disorganized Casino Jack and the United States of Money earlier this year, which ultimately let its subject wriggle off the hook, Inside Job tells its sad, sordid story clearly, concisely, and well.

The central through-line of the financial crisis by now is well-known. Basically, Wall Steet banksters — relying heavily on “market innovations” (i.e. unregulated toys) like securitization, collaterized debt obligations (CDOs) and credit default swaps — spent the first decade of the 21st century engaged in a trillion-dollar orgy of avarice, criminality, and fraud. And, a few prominent casualties like Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns aside, the perpetrators of these financial misdeeds mostly walked away unscathed from the economic devastation they wrought. In fact, they’re doing better than ever.

Said banksters got away with this from start to finish mainly becauset they could, thanks to thirty years of deregulation and an absolute bipartisan chokehold on the political process. So, when the bill came due in 2008, these masters of the free market just got the Fed to socialize their losses, thus handing the damage over to the American taxpayer by way of Secretary of the Treasury Hank Paulson (former Chairman and CEO of Goldman Sachs) and his successor, Tim Geithner (no stranger to Wall Street himself.)

As I said recently, my thoughts on the relative necessity of TARP have shifted a good deal since 2008, but, surprisingly, Ferguson doesn’t really get into that debate here. Inside Job is more broad in its focus: It aims instead to show how Wall Street has systematically corrupted both our political process and our economics departments over the course of decades, and nobody is safe from its wrath. Sure, it was probably a tremendously bad idea to let an Ayn Rand acolyte like Alan Greenspan call the shots for the American economy for so long, but he’s just the tip of the iceberg. There are other fish to fry.

After all, it is President Clinton and his financial lieutenants, Robert Rubin and Larry Summers, who preside over the death of Glass-Steagall, the original sin that precipitates all the later shenanigans. It is also they who work to keep prescient regulators like Brooksley Born from sounding the alarm. And, after the house of cards has collapsed in 2008, and President Obama steps up to the plate promising “change we can believe in,” who does he pull out of the bullpen to lead us but…the irrepressibly porcine Larry Summers and Tim Geithner, the Chair of the New York Fed? Meet the new boss, same as the old boss. (But remember, folks, Obama is really an anti-business socialist.)

What goes for the US government goes for the academy as well. As Ferguson shows, Milton Friedman aficionadoes and Reagan/Bush policy guys like Marty Feldstein of Harvard and Glenn Hubbard of Columbia, who now find themselves atop prestigious Ivy League economics departments, are all too happy to give an academic imprimatur to bad bankster behavior, as long as they see a piece of the cut. (Nobody gets it worse than Columbia prof and former Fed governor Frederic Mishkin, who appears here to have walked into a battle of wits completely unarmed.)

In the meantime, Ferguson fleshes out the documentary with related vignettes on the financial crisis and those who brought us low — some work, some don’t. The movie begins with the cautionary tale of Iceland, about as pure a real-time case study into the abysmal failures of deregulation as you can ask for. (If that doesn’t do ya, try Ireland.) But the film ends as badly as it starts well, with an overheated monologue about the way forward, cut to swelling music and images of the Statue of Liberty — a cliche that serves to dissipate much of the pent-up anger of the last 90 minutes. (Perhaps Inside Job should’ve used the lightning strike.)

What’s more, at times Ferguson seems to try too hard to frame guilty men, and never more so than when he has a former psychiatrist-to-the-bankster-stars opine about cocaine abuse and prostitution all over the Street. Sure, it’s unsavory, and I see the ultimate point here — that these petty crimes could’ve been used to flip the lower-level traders if anyone had had tried to bring a RICO case against these jokers. But this sort of bad behavior, however frat-tastically douchey, is extraneous to the real crime at hand, and it seems really out of place when you’re using fallen crusader Elliot Spitzer as a witness for the prosecution.)

Still, overall, Inside Job is a very solid documentary that manages to capture its elusive quarry, and in a better world it would result in more serious consequences for the banksters who put us in this mess. Make no mistake — this is a crime story. As Massachusetts rep Michael Capuano observes in the trailer, and as Woody Guthrie put it many moons ago, “some rob you with a six-gun, and some with a fountain pen.” Thing is, when Pretty Boy Floyd or John Dillinger robbed banks back in the day, they got shot. When the banks rob you…well, that’s apparently another thing entirely.

Groundhog Train.

In the trailer bin of late, Amtrak rider Jake Gyllenhaal is stuck in a moment he can’t get out of in our first look at Duncan Jones’ Source Code, also with Michelle Monaghan, Vera Farmiga, and Jeffrey Wright. Looks a bit too much like Tony Scott’s Deja Vu for my taste, but Jones has already earned the price of admission for this one with Moon.