At one point in Mike Nichols’ smart, surprisingly enjoyable Charlie Wilson’s War, the freewheeling, fun-loving Representative Charles Wilson (Tom Hanks), he of the Texas 2nd Congressional District, tells his schlubby, foul-mouthed partner at the CIA, Gust Avrakotos (Philip Seymour Hoffman), “You ain’t James Bond.” Deadpans Avrakotos, “You ain’t Thomas Jefferson, so let’s call it even.” True, Bond and Jefferson they’re not, but that’s actually part of the appeal of Nichols’ lively little film. A strangely optimistic, almost Capraesque movie about the covert proxy war in Afghanistan (and, ultimately, the inadvertent role played by the U.S. in fostering the Taliban), Charlie Wilson’s War — adapted by The West Wing‘s Aaron Sorkin from the book by the late George Crile — is no grim, sober-minded edutainment. Moving at a brisk clip and maintaining a light touch — too light, some might argue — throughout, the movie instead depicts how a few (relatively) ordinary, committed people can change the world…provided one of them is sitting on the House Defense Subcommittee, and has stacked up a sizable amount of chits.

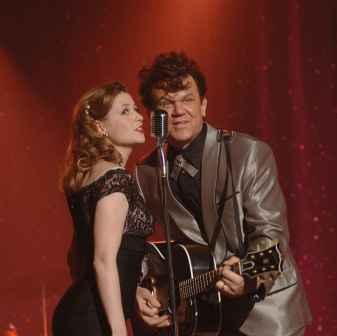

When — after a quick flash-forward setup — we first meet Congressman Charlie Wilson (Tom Hanks, eschewing the Pvt. Ryan earnestness for his more sardonic Bachelor Party/Volunteers side), he’s lounging in a Vegas hot tub with a coke-snorting television producer, a Playboy bunny, and two strippers. In short, he seems like a out-and-out cad. But there’s something endearing and even statesmanlike about his piqued interest in a 60 Minutes report, playing in the corner, on the mujahideen in Afghanistan. (Maybe it’s the Dan Rather Texas connection.) Delving further into the issue back in Washington, Wilson — exercising the power of his crucial committee position — singlehandedly doubles U.S. funding of the mujahideen from $5 million to $10 million. This by-all-accounts token gesture draws the attention of the wealthy Houston socialite Joanne Herring (Julia Roberts, solid), a woman with money, connections, and a fervent commitment to anticommunism, and she sends Wilson off to Pakistan to meet with President Zia-ul-Haq about the situation in neighboring Afghanistan. There, Wilson is moved to the cause by the sight of a dismal refugee camp, and soon enough, he’s enlisted an important ally in Avrakotos, a profane Langley veteran (Hoffman, showing yet another side after Before the Devil and The Savages this year, and nearly running away with the movie.) Together, these three — Wilson, Herring, Avrakotos (John Rambo’s unique contributions to the cause of Afghan freedom are sadly overlooked — set in motion a scheme not only to increase funding radically for the war but to funnel Soviet weaponry owned by Israel and Egypt to the freedom fighters there. Of course, some delicate diplomacy is required, and, in any case, giving Afghan youths an arsenal of helicopter-slaying RPGs doesn’t seem like such a great an idea in retrospect…

While nodding to the dismal events that follow American intervention in the region, Charlie Wilson’s War hardly dwells on the blowback, or on anything — a few refugee camp horror stories and a Pavel Lychnikoff cameo notwithstanding — that might interrupt its tone of hearty, back-slapping jocularity. (Supporting turns by Amy Adams, Emily Blunt, Ned Beatty, Denis O’Hare, John Slattery, and Peter Gerety help speed things along in a comfortable groove.) And yet, however feel-good, Wilson ultimately feels more ripped from the headlines than even the filmmakers could’ve guessed. Some lawmakers have trouble distinguishing between Pakistan and Afghanistan at one point, and Herring begins an introduction of Pakistan’s President by saying, “Zia did not kill Bhutto.” (Leavening the chill that follows this now-eerie moment, Rudy Giuliani and John Murtha also come up at various times as punchlines.)

But, its timeliness and prescience aside, what I found most impressive about Charlie Wilson’s War is how aptly it portrays the feel of Washington. This was somewhat surprising to me as, while I liked Sorkin’s The West Wing decently enough as a TV drama and admired its general idealism about politics, the show always felt rather fake to me. But, be it due to Crile or Sorkin or Nichols, Wilson conveys a lot of the telling details of life inside the Beltway quite well — the hallway horse-trading and neverending quid pro quos, the simultaneous meetings, the bland, institutional cafeterias; the bevy of youngish staffers (and inordinately pretty administrative assistants) on Capitol Hill, the deals crafted over dinner or drinks, the conference calls, the memory holes, myopic thinking, and CYA behavior. Outside of The Wire‘s nuanced take on the compromises of Baltimore city politics, it’s hard to think of a more on-target recent portrayal of the (non-campaigning) political process. Sadly, for Congressman Wilson as for today’s legislators, fiddling with the internal dynamics of far-flung nations we barely understand for short-term gain is All in the Game. Still, as Charlie Wilson’s War proves, don’t let it ever be said that nothing gets done in Washington.