Well, there are still a number of flicks I haven’t yet seen — David Lynch’s Inland Empire, for example, which I hope to hit up this weekend. But as the Oscar nods were announced today, and as the few remaining forlorn Christmas trees are finally being picked up off the sidewalk, now seems the last appropriate time to crank out my much belated end-of-2006 film list (originally put off to give me time to make up for my New Zealand sojourn.) To be honest, I might’ve written this list a few weeks earlier, had it not happened that I ended up seeing the best film of 2005 in mid-January of last year, thus rendering the 2005 list almost immediately obsolescent. But, we’ll get to that — As it stands, 2006 was a decent year in movies (in fact a better year in film than it was in life, the midterms notwithstanding), with a crop of memorable genre flicks and a few surprisingly worthy comebacks. And, for what it’s worth, I thought the best film released in 2006 was…

Top 20 Films of 2006

[2000/2001/2002/2003/2004/2005]

1. United 93: A movie I originally had no interest in seeing, Paul Greengrass’s harrowing docudrama of the fourth flight on September 11 captured the visceral shock of that dark day without once veering into exploitation or sentimentality (the latter the curse of Oliver Stone’s much inferior World Trade Center.) While 9/11 films of the future might offer more perspective on the origins and politics of those horrible hours, it’s hard to imagine a more gripping or humane film emerging anytime soon about the day’s immediate events. A tragic triumph, United 93 is an unforgettable piece of filmmaking.

[1.] The New World (2005): A movie which seemed to divide audiences strongly, Terence Malick’s The New World was, to my mind, a masterpiece. I found it transporting in ways films seldom are these days, and Jamestown a much richer canvas for Malick’s unique gifts than, say, Guadalcanal. As the director’s best reimagining yet of the fall of Eden, The New World marvelously captured the stark beauty and sublime strangeness of two worlds — be they empires, enemies, or lovers — colliding, before any middle ground can be established. For its languid images of Virginia woodlands as much as moments like Wes Studi awestruck by the rigid dominion over nature inherent in English gardens, The New World goes down as a much-overlooked cinematic marvel, and (sorry, Syriana) the best film of 2005.

2. Letters from Iwo Jima: Having thought less of Flags of our Fathers and the woeful Million Dollar Baby than most people, I was almost completely thrown by the dismal grandeur and relentless gloom of Eastwood’s work here. To some extent the Unforgiven of war movies, Iwo Jima is a bleakly rendered siege film that trafficks in few of the usual tropes of the genre. (Don’t worry — I suspect we’ll get those in spades in two months in 300.) Instead of glorious Alamo-style platitudes, we’re left only with the sight of young men — all avowed enemies of America, no less — swallowed up and crushed in the maelstrom of modern combat. From Ken Watanabe’s commanding performance as a captain going down with the ship to Eastwood’s melancholy score, Letters works to reveal one fundamental, haunting truth: Tyrants may be toppled, nations may be liberated, and Pvt. Ryans may be saved, but even “good wars” are ultimately Hell on earth for those expected to do the fighting.

3. Children of Men: In the weeks since I first saw this film, my irritation with the last fifteen minutes or so has diminished, and Alfonso Cuaron’s Children of Men has emerged for what it is — one of the most resonant “near-future” dystopias to come down the pike in a very long while, perhaps since (the still significantly better) Brazil. Crammed with excellent performances by Clive Owen, Michael Caine, Chiwetel Ejiofor and others, Children is perhaps a loosely-connected grab bag of contemporary anxieties and afflictions (terrorism, detainment camps, pharmaceutical ads, celebrity culture). But it’s assuredly an effective one, with some of the most memorable and naturalistic combat footage seen in several years to boot. I just wished they’d called that ship something else…

4. Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan: True, the frighteningly talented Sasha Baron Cohen spends a lot of time in this movie shooting fish in a barrel, and I wish he’d spent a little more time eviscerating subtler flaws in the American character than just knuckle-dragging racists and fratboy sexists. Still, the journeys of Borat Sagdiyev through the Bible Buckle and beyond made for far and away the funniest movie of the year. Verry nice.

5. The Prestige: I originally had this in Children of Men‘s spot, as there are few films I enjoyed as much this year as Christopher Nolan’s sinister sleight-of hand. But, even after bouncing Children up for degree of difficulty, that should take nothing away from The Prestige, a seamlessly made genre film about the rivalries and perils of turn-of-the-century prestidigitation. (There seems to be a back-and-forth between fans of this film and The Illusionist, which I sorta saw on a plane in December. Without sound (which, obviously, is no way to see a movie), Illusionist seemed like an implausible love story set to a tempo of anguished Paul Giamatti reaction shots. In any case, I prefer my magic shows dark and with a twist.) Throw in extended cameos by David Bowie and Andy Serkis — both of which help to mitigate the Johansson factor — and The Prestige was the purest cinematic treat this year for the fanboy nation. Christian Bale in particular does top-notch work here, and I’m very much looking forward to he and Nolan’s run-in with Heath Ledger’s Joker in The Dark Knight.

6. The Fountain: Darren Aronofsky’s elegiac ode to mortality and devotion was perhaps the most unfairly maligned movie of the year. (In a perfect world, roughly half of the extravagant praise going to Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth would have been lavished on this film.) Clearly a heartfelt and deeply personal labor of love, The Fountain — admittedly clunky in his first half hour — was a visually memorable tone poem that reminds us that all things — perhaps especially the most beautiful — are finite, so treasure them while you can.

7. The Queen: A movie I shied away from when it first came out, The Queen is a canny look at contemporary politics anchored by Helen Mirren’s sterling performance as the fastidious, reserved, and ever-so-slightly downcast monarch in question. (Michael Sheen’s Tony Blair is no slouch either.) In fact, The Queen is the type of movie I wish we saw more often: a small, tightly focused film about a very specific moment in recent history. Indeed, between this and United 93, 2006 proved to be a good year for smart and affecting depictions of the very recent past — let’s hope the trend continues through the rest of the oughts.

8. Inside Man: The needless Jodie Foster subplot notwithstanding, Spike Lee’s Inside Man was a fun, expertly-made crime procedural, as good in its own way as the much more heavily-touted Departed. It was also, without wearing it on its sleeve, the film Crash should have been — a savvy look at contemporary race relations that showed there are many more varied and interesting interactions between people of different ethnicities than simply “crashing” into each other. (But perhaps that’s how y’all roll over in car-culture LA.) At any rate, Inside Man is a rousing New York-centric cops-and-robbers pic in the manner of Dog Day Afternoon or The Taking of the Pelham One Two Three, and it’s definitely one of the more enjoyable movie experiences of the year.

9. Dave Chappelle’s Block Party: Speaking of enjoyable New York-centric movie experiences, Dave Chappelle and Michel Gondry’s block party last year felt like a breath of pure spring air after a long, cold, lonely winter — time to kick off the sweaters and parkas and get to groovin’ with your neighbors. With performances by some of the most innovative and inspired players in current hip-hop (Kanye, Mos Def, The Roots, The Fugees, Erykah Badu), and presided over by the impish, unsinkable Chappelle, Block Party was one of the best concert films in recent memory, and simply more fun than you can shake a stick at.

10. Casino Royale: Bond is back! Thanks to Daniel Craig’s portrayal of 007 as a blunt, glitched-up human being rather than a Casanova Superspy, and a script that eschewed the UV laser pens and time-release exploding cufflinks of Bonds past for more hard-boiled and gritty fodder, Casino Royale felt straight from the pen of Ian Fleming, and newer and more exciting than any 007 movie in decades.

11. The Departed: A very good movie brimming over with quality acting (notably Damon and Di Caprio) and support work — from Mark Wahlberg, Alec Baldwin, Vera Farmiga, Ray Winstone, and others — Scorsese’s The Departed also felt a bit too derivative of its splendid source material, Infernal Affairs, to merit the top ten. And then there’s the Jack problem: An egregiously over-the-top Nicholson chews so much scenery here that it’s a wonder there’s any of downtown Boston left standing. But, despite these flaws, The Departed is well worth seeing, and if it finally gets Scorsese his Best Director Oscar (despite Greengrass deserving it), it won’t be too much of an outrage.

[11.] Toto The Hero (1991): Also sidelined out of this top twenty on account of its release date, Jaco Von Dormael’s Toto the Hero — Terry Gilliam’s choice of screening for an IFC Movie Night early in October — is definitely one for the Netflix queue, particularly if you’re a fan of Gilliam’s oeuvre. It’s a bizarre coming-of-age/going-of-age tale that includes thoughts of envy, murder, incest, and despair, all the while remaining somehow whimsical and fantastical at its core. (And, trust me: As with Ary Borroso’s “Brazil“, you’ll be left humming Charles Trenet’s “Boum” to yourself long after the movie is over.)

12. Tristam Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story: I guess this is where I should be writing something brief and scintillating about Michael Winterbottom’s metanarrative version of Laurence Sterne’s famous novel, one which gives Steve Coogan — and the less well-known Rob Brydon — a superlative chance to work their unique brand of comedic mojo. But I’m growing distracted and Berk has that pleading “I-want-to-go-out, are-you-done-yet” look and Kevin’s still only on Number 12 of a list that, for all intent and purposes, is three weeks late and will be read by all of eight people anyway. (But don’t tell him that — In fact, I shouldn’t even talk about him behind his back.) So, perhaps we’ll come back to this later…it’s definitely a review worth writing (again), if I could just figure out how to start.

13. Miami Vice: Michael Mann’s moody reimagining of the TV show that made him famous isn’t necessarily his best work, but it was one of the more unique and absorbing movies of the summer, and one that lingers in the memory long after much of the year’s fluffier and more traditional films have evaporated. Dr. Johnson (and Hunter Thompson) once wrote that “He who makes a beast out of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man.” I guess that’s what Crockett and Tubbs are going for with the nightclubs and needle boats.

14. CSA: The Confederate States of America: I wish I were in the land of cotton…or have we been there all along? Kevin Wilmott’s alternate history of a victorious Confederate America is a savvy and hilarious send-up of history documentaries and a sharp-witted, sharp-elbowed piece of satire with truths to tell about the shadow of slavery in our past. With any luck, CSA will rise again on the DVD circuit.

15. The Science of Sleep: Not as good or as universally applicable as his Eternal Sunshine (the best film of 2004), Michel Gondry’s dreamlike, unabashedly romantic The Science of Sleep is still a worthy inquiry into matters of the (broken) heart. What is it about new love that is so intoxicating? And why do the significant others in our mind continue to haunt us so, even when they bear such little relation to the people they initially represented? Science doesn’t answer these crucial questions (how can it?), but it does acutely diagnose the condition. When it comes to relationships, Sleep suggests, all we have to do — sometimes all we can do, despite ourselves — is dream.

16. Rocky Balboa: Rocky! Rocky! Rocky! I’m as surprised as anyone that Sly’s sixth outing as Philadelphia’s prized pugilist made the top twenty. But, as formulaic as it is, Rocky Balboa delivered the goods like a Ivan Drago right cross. Ultimately not quite as enjoyable as Bond’s return to the service, Rocky Balboa still made for a commendable final round for the Italian Stallion. And, if nothing else, he went down fighting.

17. Pan’s Labyrinth: A fantasy-horror flick occurring simultaneously within a Spanish Civil War film, Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth ultimately felt to me like less than the sum of its parts. But if the plaudits it’s receiving help to mainstream other genre movies in critics’ eyes in the future, I’m all for it. It’s an ok movie, no doubt, but if you’re looking for to see one quality supernatural-historical tale of twentieth-century Spain, rent del Toro’s The Devil’s Backbone instead.

18. Little Miss Sunshine: Another film which I think is being way overpraised, Little Miss Sunshine is still a moderately enjoyable evening at the movies. It felt overscripted and television-ish to me, and I wish it was as way over yonder in the minor key as it pretends to be, but Sunshine is nevertheless a cute little IFC-style family film, and one that does have a pretty funny payoff at the end.

19. The Last King of Scotland: I just wrote on this one yesterday, so my impressions haven’t changed much. Still, Forrest Whitaker’s jovial and fearsome Idi Amin, and an almost-equally-good performance by James McAvoy as the dissolute young Scot who unwittingly becomes his minion, makes The Last King of Scotland worth seeing, if you can bear its grisly third act.

20. Thank You for Smoking: It showed flashes of promise, and it was all there on paper, in the form of Chris Buckley’s book. But Smoking, alas, never really lives up to its potential. What Smoking needed was the misanthropic jolt and sense of purpose of 2005’s Lord of War, a much more successful muckraking satire, to my mind. But Smoking, like its protagonist, just wants to be liked, and never truly commits to its agenda. Still, pleasant enough, if you don’t consider the opportunity cost.

Most Disappointing: All the King’s Men, X3: The Last Stand — Both, unfortunately, terrible.

Worth a Rental: A Scanner Darkly, Brick, Cache, Cars, Curse of the Golden Flower, Glory Road, The History Boys, Marie Antoinette, Match Point (2005), V for Vendetta, Why We Fight

Don’t Bother: Bobby, Crash (2005), The Da Vinci Code, Flags of our Fathers, The Good German, The Good Shepherd, Mission: Impossible: III, Night Watch (2004), Pirates of the Caribbean 2: Dead Men’s Chest, Poseidon, Scoop, Superman Returns, The Wicker Man, World Trade Center

Best Actor: Clive Owen, Children of Men; Forrest Whitaker, The Last King of Scotland; Ken Watanabe, Letters from Iwo Jima

Best Actress: Helen Mirren, The Queen; Q’Orianka Kilcher, The New World

Best Supporting Actor: Mark Wahlberg, The Departed; Michael Caine, Children of Men/The Prestige

Best Supporting Actress: Pam Farris, Children of Men; Vera Farmiga, The Departed; Maribel Verdu, Pan’s Labyrinth

Unseen: Apocalypto, Babel, Blood Diamond, Catch a Fire, Clerks II, The Descent, The Devil Wears Prada, Dreamgirls, Fast Food Nation, Hollywoodland, An Inconvenient Truth, Infamous, Inland Empire, Jackass Number Two, Jet Li’s Fearless, Lassie, Little Children, Notes from a Scandal, The Notorious Betty Page, A Prairie Home Companion, The Pursuit of Happyness, Running With Scissors, Sherrybaby, Shortbus, Stranger than Fiction, Tideland, Venus, Volver, Wordplay

2007: The list isn’t looking all that great, to be honest. But, perhaps we’ll find some gems in here…: 300, 3:10 To Yuma, Beowulf, Black Snake Moan, The Bourne Ultimatum, FF2, The Golden Age: Elizabeth II, The Golden Compass, Grindhouse, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Hot Fuzz, I Am Legend, Live Free or Die Hard, Ocean’s Thirteen, PotC3, The Simpsons Movie, Smokin’ Aces, Spiderman 3, Stardust, The Transformers, Zodiac.

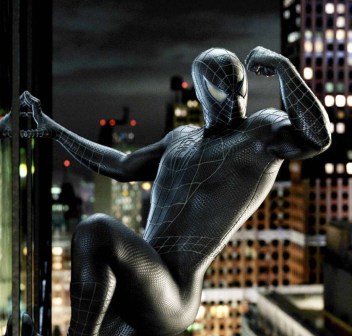

Sam Raimi’s Spiderman 3, which I saw a week ago, before this recent illness descended in earnest, is — as you likely already know — a disappointment. Both undercooked and overstuffed, it oftens feels like a Sequel-By-Numbers, the creation of a boardroom of comic-book-ignorant Sony suits who sat down and watched the splendid Spiderman 2, brainstormed for two hours about what its main selling points were, and tried to add 20% more of each to Spidey 3. The end result, as Joseph II might say, has too many notes. There occasionally seems to be a decent, heartfelt Sam Raimi Spidey foray struggling to get out in here somewhere, but it’s mostly wrapped up and powerless against the black suit of the corporate bottom line. I highly doubt this film will be the end of Spiderman, after that outrageous opening weekend take, but it does sadly suggest that it may be time for Raimi & co. to escape Spidey’s web and take a break from the franchise.

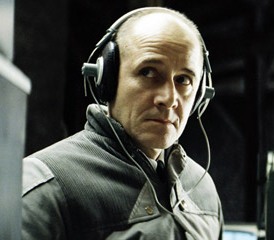

Sam Raimi’s Spiderman 3, which I saw a week ago, before this recent illness descended in earnest, is — as you likely already know — a disappointment. Both undercooked and overstuffed, it oftens feels like a Sequel-By-Numbers, the creation of a boardroom of comic-book-ignorant Sony suits who sat down and watched the splendid Spiderman 2, brainstormed for two hours about what its main selling points were, and tried to add 20% more of each to Spidey 3. The end result, as Joseph II might say, has too many notes. There occasionally seems to be a decent, heartfelt Sam Raimi Spidey foray struggling to get out in here somewhere, but it’s mostly wrapped up and powerless against the black suit of the corporate bottom line. I highly doubt this film will be the end of Spiderman, after that outrageous opening weekend take, but it does sadly suggest that it may be time for Raimi & co. to escape Spidey’s web and take a break from the franchise. In true comic-book fashion, Spiderman 3 begins basically where the last installment left off, with Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson (Tobey Maguire and Kirsten Dunst, both of whom seem bored) in love, his secret identity out to her. But, just as our friendly neighborhood webslinger begins to contemplate wedding bells in his future, a slew of supervillains rise up to disturb Spidey’s domestic peace: The Green Goblin II (James Franco, putting in his best work of the series), who’s also aware of Spidey’s identity and is out to avenge his father’s death; The Sandman (Thomas Haden Church, good with what he’s given), who’s out to find his daughter some quality affordable health care (good luck! Even fantasy has limits); and, most troubling, Venom (ultimately, Topher Grace, a likable actor that sadly doesn’t work here), an oozing alien symbiote that first draws out Spiderman’s dark side before congealing with his biggest rival at the Daily Bugle, photoshop expert Eddie Brock. Eventually, Spidey must find a way not only to beat back this rogues’ gallery before doom befalls Ms. Watson high above Manhattan, but also come to terms with his darkest impulses, grapple with his deepfelt desire to cut a rug in a jazz club, and make Mary Jane feel important and special despite her withholding secrets from Peter most of the movie for unexplainable reasons. Can he pull it off, Spider-fans?

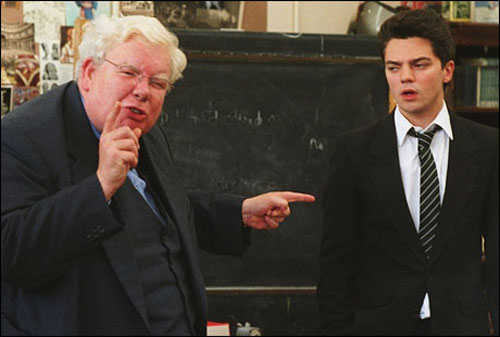

In true comic-book fashion, Spiderman 3 begins basically where the last installment left off, with Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson (Tobey Maguire and Kirsten Dunst, both of whom seem bored) in love, his secret identity out to her. But, just as our friendly neighborhood webslinger begins to contemplate wedding bells in his future, a slew of supervillains rise up to disturb Spidey’s domestic peace: The Green Goblin II (James Franco, putting in his best work of the series), who’s also aware of Spidey’s identity and is out to avenge his father’s death; The Sandman (Thomas Haden Church, good with what he’s given), who’s out to find his daughter some quality affordable health care (good luck! Even fantasy has limits); and, most troubling, Venom (ultimately, Topher Grace, a likable actor that sadly doesn’t work here), an oozing alien symbiote that first draws out Spiderman’s dark side before congealing with his biggest rival at the Daily Bugle, photoshop expert Eddie Brock. Eventually, Spidey must find a way not only to beat back this rogues’ gallery before doom befalls Ms. Watson high above Manhattan, but also come to terms with his darkest impulses, grapple with his deepfelt desire to cut a rug in a jazz club, and make Mary Jane feel important and special despite her withholding secrets from Peter most of the movie for unexplainable reasons. Can he pull it off, Spider-fans? Maybe so, but the movie sure can’t. If that litany of villains put you in mind of the later installments of the Batman franchise, Batman Forever or Batman and Robin, you’re in the right ballpark. Basically, Raimi has too many balls in the air this time around (I haven’t even mentioned Gwen Stacey, who’s also in here for some reason), and the film just can’t do justice to all of them. The Sandman in particular is given short shrift — much time is devoted to giving him a backstory, but it gets dropped halfway through and never amounts to much. Meanwhile, other important plot points, such as how Spidey’s enemies decide to gang up on him, are handled perfunctorily, apparently to make room for more wet blanket Mary Janeisms or badly-conceived comedy involving J. Jonah Jameson (J.K. Simmons). By the end of the film, when Harry Osborne’s butler becomes Basil Exposition and Spiderman runs around without a mask in front of hundreds of cameras, the carelessness taken with this installment of the franchise becomes manifest. Raimi would likely have done better to leave Venom out of this episode and saved him for the next one (and, indeed, circumstantial evidence suggests that Venom was foisted on him by Sony — Raimi wanted the Vulture.) As it is, though, Spiderman 3 is a swing-and-a-miss — not as bad as X3, mind you, but definitely the worst outing thus far in the Spidey franchise. ‘Nuff said.

Maybe so, but the movie sure can’t. If that litany of villains put you in mind of the later installments of the Batman franchise, Batman Forever or Batman and Robin, you’re in the right ballpark. Basically, Raimi has too many balls in the air this time around (I haven’t even mentioned Gwen Stacey, who’s also in here for some reason), and the film just can’t do justice to all of them. The Sandman in particular is given short shrift — much time is devoted to giving him a backstory, but it gets dropped halfway through and never amounts to much. Meanwhile, other important plot points, such as how Spidey’s enemies decide to gang up on him, are handled perfunctorily, apparently to make room for more wet blanket Mary Janeisms or badly-conceived comedy involving J. Jonah Jameson (J.K. Simmons). By the end of the film, when Harry Osborne’s butler becomes Basil Exposition and Spiderman runs around without a mask in front of hundreds of cameras, the carelessness taken with this installment of the franchise becomes manifest. Raimi would likely have done better to leave Venom out of this episode and saved him for the next one (and, indeed, circumstantial evidence suggests that Venom was foisted on him by Sony — Raimi wanted the Vulture.) As it is, though, Spiderman 3 is a swing-and-a-miss — not as bad as X3, mind you, but definitely the worst outing thus far in the Spidey franchise. ‘Nuff said.