To his credit, Steven Soderbergh is relentlesssly experimental. When he’s at the top of his game (Out of Sight, Traffic, The Limey), few directors are better at telling stories that move with purpose and imagination, and even some of his resolutely mainstream projects (Erin Brockovich, Ocean’s 11, Ocean’s 12) –which might have been staid and forgettable in someone else’s hands — have verve and originality to spare. But, even for a guy as talented as Soderbergh, you keep taking swings, and eventually you’re going to whiff a few. (Full Frontal and Kafka come to mind — I haven’t seen Schizopolis or Bubble, but have heard they might be in this category too.) Alas, Stephen Soderbergh’s period noir, The Good German, is in this latter camp. Written with a 21st century sophistication about sex and language but filmed in the manner of a 1940s war flick — back projections, ancient credits, garish score, and all — German basically comes across as a two-hour gimmick, one that sadly outlasts its welcome by the second reel. George Clooney and Cate Blanchett do what they can (and both look great in B&W), but, surprisingly, the film just never engages — it feels flat and uninvolving from start to finish. In sum, as with the Solaris remake, Soderbergh and Clooney’s errant stab at big-think sci-fi, The Good German feels fundamentally misconceived.

Berlin, 1945. The war in Europe is over, and, divided into four sectors by the victorious Allies, Germany’s capital is now a sordid morass of blackened buildings and anything-goes. Venturing into the urban decay is former resident Jake Geismer (Clooney), now a TNR correspondent sent to cover the Potsdam Conference (which in its own way feels as improbable as Ocean buddy Matt Damon playing a 45-year-old in The Good Shepherd.) But, not ten minutes back in town, Geismer’s wallet is stolen by his too-friendly-by-half army driver (Tobey Maguire, laughably miscast), who, as it so happens, is a well-connected black marketeer, a despicable lout, and the current boyfriend and pimp of Geismer’s old flame, Lena Brandt (Blanchett). After a body shows up at Potsdam, and after that old flame is rekindled, Geismer finds himself tracking down a story that may or may not involve hidden war crimes, atomic secrets, Russian n’er do wells, German scientists, his old prosecutor buddy (Leland Orser), and of course, Lena, a girl who — like so many residents in her fallen city — has faced unspeakable horrors and kept them under wraps.

All well and good…who doesn’t enjoy a seamy noir? But, The Good German is curiously inert, and never gets off the tarmac. The plot ends up being byzantine in its mechanics, as a decent detective story should be, but German never arouses enough interest to makes the many twists and turns feel earned. Tobey Maguire doesn’t help — A decent actor with the right material (say, as Peter Parker), he’s so woefully bad here that it kills the movie from the start. (Also, a random quibble: Maguire also beats up Clooney at one point, as Clooney’s Geisberg is of the Tom Reagan school of noir heroes: he gets his ass kicked a lot. But, unless this is Golden Age Spiderman or something, it makes very little sense here.) But equally jarring is the disparity between the script and the look in The Good German: The period recreation, however clever at times, ends up distracting from rather than enhancing the tale being told. In all honesty, it just doesn’t work.

If The Good German does offer any distinct pleasures, they’re mostly in the margins. Deadwood‘s Robin Weigert (a.k.a. Calamity Jane) plays pretty far from type — the blunt-spokenness notwithstanding — as Lena’s brash, hooker roommate. And, even despite the general failure here, Soderbergh still has a great eye, and the black-and-white cinematography does pay occasional dividends (despite many of the outdoor scenes having a grainy, washed-out look to them.) Speaking of which, I’d be remiss if I didn’t note that the highlight of The Good German for me was Soderbergh’s framing of Cate Blanchett as a classic screen siren. True, her femme fatale accent occasionally lapses into something more like Natasha from Rocky and Bullwinkle than Garbo or Dietrich. But, a beautiful woman under any circumstances, Blanchett often looks breathtaking here, what with all the period accoutrements and chiaroscuro lighting at her service. Careful, Jake, it’s Berlintown…and she’s going to play you for a fool, yes it’s true.

Well, I’m not very happy about being on the other end of the review spectrum for this film, which was one I’d been really looking forward to. But, I must confess, I’m somewhat mystified by the

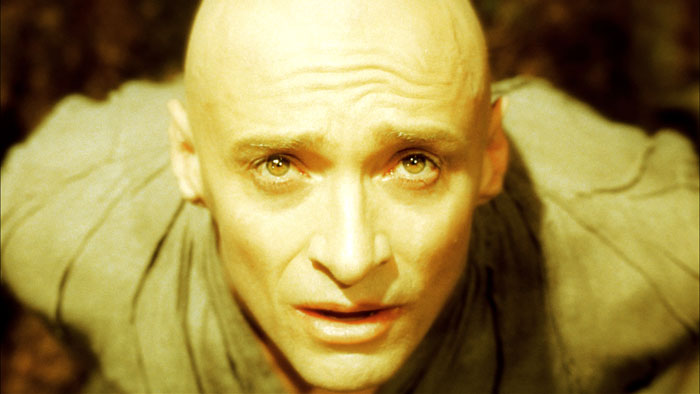

Well, I’m not very happy about being on the other end of the review spectrum for this film, which was one I’d been really looking forward to. But, I must confess, I’m somewhat mystified by the  So, here’s the setup: Once upon a time — 1944, to be exact — there was a young girl on the verge of adolescence named Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) who was forced to accompany her sickly, pregnant mother (Ariadna Gil) into the Spanish countryside, and to live with her wicked (Fascist) stepfather (Sergi Lopez of

So, here’s the setup: Once upon a time — 1944, to be exact — there was a young girl on the verge of adolescence named Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) who was forced to accompany her sickly, pregnant mother (Ariadna Gil) into the Spanish countryside, and to live with her wicked (Fascist) stepfather (Sergi Lopez of  But do they collide? Perhaps I missed some vital subtext, but I found Ofelia’s dreamworld adventures — other than the “Girl, you’ll be a Woman soon” flourishes, like the bloody book — to be generally remote both from her problems at home and from the Republican-Fascist feud, other than that all three narrative strands grow increasingly grisly and grotesque. And, while certain scenes definitely linger in the senses like eerie reminiscences of a fever dream, most notably the Wraith’s Table, they don’t really serve the larger story in any way I could fathom. (Also, why does Ofelia suddenly decide to go all Augustus Gloop in that scene anyway? Dream logic, I guess, but it seemed out of character.) Throw in a few second-act torture scenes that are more off-putting than they are resonant or even necessary, and Labyrinth starts to wear thin well before the end. In sum, Pan‘s a decent film that’s worth seeing if you’re in the mood for it, but it’s by no means the genre classic it’s being made out to be. Perhaps the subtitles gave it gravitas in some corners, but, to my mind, Pan’s Labyrinth gets a little lost in its own maze.

But do they collide? Perhaps I missed some vital subtext, but I found Ofelia’s dreamworld adventures — other than the “Girl, you’ll be a Woman soon” flourishes, like the bloody book — to be generally remote both from her problems at home and from the Republican-Fascist feud, other than that all three narrative strands grow increasingly grisly and grotesque. And, while certain scenes definitely linger in the senses like eerie reminiscences of a fever dream, most notably the Wraith’s Table, they don’t really serve the larger story in any way I could fathom. (Also, why does Ofelia suddenly decide to go all Augustus Gloop in that scene anyway? Dream logic, I guess, but it seemed out of character.) Throw in a few second-act torture scenes that are more off-putting than they are resonant or even necessary, and Labyrinth starts to wear thin well before the end. In sum, Pan‘s a decent film that’s worth seeing if you’re in the mood for it, but it’s by no means the genre classic it’s being made out to be. Perhaps the subtitles gave it gravitas in some corners, but, to my mind, Pan’s Labyrinth gets a little lost in its own maze.