To be honest, for some reason or another, I don’t really feel the inclination to write the usual three-paragraph review for Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, so I’ll just leave it at this: It’s really funny. Yes, several of the best moments — the “war of terror” speech, the “Not” joke, etc. — are in the ads, but, really, those only scratch the surface of the madness here. (As an aside, why is it that people seem to laugh hardest at jokes they’ve already heard? Must be an inclusiveness thing. I saw the movie on Friday afternoon with a packed audience, so it’s not like these were folks who hadn’t caught the trailer 1000 times.) At any rate, unless you’re offended by ridiculously over-the-top anti-semitism or have a problem with truly grotesque displays of male nudity, you should find it verrry nice. (But leave the gypsys at home.)

Category: Reviews

Flagging Fathers.

As its conceit, the film follows the six soldiers pictured in the famous photograph of the Iwo Jima flag-raising, of which only three made it out alive: John “Doc” Bradley (Ryan Phillipe, better than usual), Rene Gagnon (Jesse Bradford), and Ira Hayes (Adam Beach, also very good). As it turns out, surviving hell on earth was only the first of their trials: Once the federal agitprop powers-that-be figure out what a spectacular image they’ve stumbled upon, these three soldiers — who in fact were putting up the second flag of the day — are forced into a whirlwind publicity tour across the United States to drum up support for war bonds. For Gagnon (and his ridiculously golddiggerish fiancee), this is an unexpected stroke of luck. For Bradley, this is grist for several artfully timed flashbacks of the actual battle. And for Hayes, a Pima Indian forced to confront not only the twin demons of racism and alcoholism but also his own feelings of guilt and inadequacy on the road, the war bond schmooze train seems like it might just be worse than the battlefield… (There’s also a framing device involving Bradley’s son (the author of the book) interviewing the participants in the story, but it’s basically Greatest Generation filler.)

Between the battle itself and the opportunity for trenchant social criticism offered by the war bond tour, this may sound like it has all the makings for a quality film. And, to their credit, the players all acquit themselves decently, with lots of good character actors (say, Robert Patrick, Harve Presnell, and look for Luther of The Warriors (David Patrick Kelly) in a cameo as Harry Truman) around to leaven the likes of grunts Paul Walker and Jamie Bell. That being said, virtually every character in Flags comes across as shallow and inert: From start to finish, Bradley’s a polite, well-meaning cipher, Gagnon a boyish opportunist, and Hayes a weepy drunk, and they’re the well-rounded ones. Moreover, as Ed Gonzalez of The House Next Door aptly put it, “the stink of Crash hovers over Flags of Our Fathers.” Cheap, reflexive sentiment is the order of the day here, and even scenes that should be powerful — say, Hayes being refused service at a white-only bar, or America learning of the death of FDR over the radio — are ruined by Haggis’s usual brand of in-your-face hokum, baldly sentimentalized and applied as a paste. By the time we’re forced to sit through some deathbed histrionics about daddys and heroes — a scene which would seem to undermine the film’s earlier emphasis on not valorizing war simply for its own sake — I’d pretty much completely checked out of the film. In short, Flags of our Fathers means well, I suppose…but it’s far too saccharine here to do its subject justice, and is basically a long-winded, ill-conceived bore.

Absolutely Sweet Marie.

In my generally positive review of Lost in Translation a few years back, I complained that “this story could only have been written by deeply privileged people.” Well, Sofia Coppola’s newest film, Marie Antoinette, makes Lost in Translation seem like a working-class anthem. To be honest, I find my thoughts dwelling on Marie Antoinette in the few days since I saw it, and I’m liking it better in retrospect than I did while actually watching the movie. Still, Coppola’s film seems narrowly conceived to a fault. It conveys both the life-on-Mars quality of Versailles and the innocent decadence of privileged youth decently well (even if Antoinette was almost 35 by the time of the Revolution), but, in my humble opinion, the movie needed a lot more politics and a lot less in the way of shoes and pastries. As it is, despite all the wallowing in material delights, Marie Antoinette displays little in the way of a narrative arc, and, to my mind, it felt both unfinished and unsatisfying.

In my generally positive review of Lost in Translation a few years back, I complained that “this story could only have been written by deeply privileged people.” Well, Sofia Coppola’s newest film, Marie Antoinette, makes Lost in Translation seem like a working-class anthem. To be honest, I find my thoughts dwelling on Marie Antoinette in the few days since I saw it, and I’m liking it better in retrospect than I did while actually watching the movie. Still, Coppola’s film seems narrowly conceived to a fault. It conveys both the life-on-Mars quality of Versailles and the innocent decadence of privileged youth decently well (even if Antoinette was almost 35 by the time of the Revolution), but, in my humble opinion, the movie needed a lot more politics and a lot less in the way of shoes and pastries. As it is, despite all the wallowing in material delights, Marie Antoinette displays little in the way of a narrative arc, and, to my mind, it felt both unfinished and unsatisfying.

As the film begins, mirthful 14-year-old free spirit Marie Antoinette (Kirsten Dunst) has just been married off by her mother, the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria (Marianne Faithful), to the pudgy, young, and introverted dauphin of France, Louis XIV (Jason Schwartzman). And so we spend the first forty minutes of the film following young Marie’s introduction to the cauldron of social intrigue that is Versailles, where she is shuffled to and fro by her grim handler, the Comtesse de Noailles (Judy Davis, looking like the Borg Queen), and becomes the target of a whispering campaign due to her still-unconsummated marriage (a plot point that doesn’t work at all, given how far Dunst and Schwartzman are from 14 and 15 respectively.) At any rate, eventually Marie makes a few friends — most notably the Duchesse de Polignac (Rose Byrne) — and a few enemies, such as Madame Du Barry (Asia Argento), courtesan to Louis XV (Rip Torn). And she picks up several bad habits, including but not limited to gambling, shopping, all-night festivities, and the Count Axel von Fersen (Jamie Dornan), most of which are scored — usually pretty effectively — to post-punk or new wave tracks by Gang of Four (“Natural’s Not in It”), New Order (“Ceremony”), The Cure (“Plainsong”), and others.

Of course, as we all know, the party can’t last forever, and Marie Antoinette’s reveries have a particularly nasty end. But the Revolution only takes up about fifteen minutes of the film here, and in fact is basically sidestepped (which feels a bit like making a movie about the Titanic and skipping the iceberg, but ah well.) Obviously, it was Coppola’s artistic decision not to wallow in the horrors that beset Antoinette’s final years, but that same lack of focus about anything other than good times at Versailles mars the rest of the film. Contrary to the figure portrayed here, Antoinette was engaged in the political issues facing her kingdom, particularly late in her reign. But, here’s she seems just a poor-little-rich-party-girl until the merde hits the fan in a big way in 1789. (There are a few scenes involving the French decision to aid the American Revolutionaries, I guess, but they seem unconnected to everything else going on and are in effect shoehorned in.)

Of course, as we all know, the party can’t last forever, and Marie Antoinette’s reveries have a particularly nasty end. But the Revolution only takes up about fifteen minutes of the film here, and in fact is basically sidestepped (which feels a bit like making a movie about the Titanic and skipping the iceberg, but ah well.) Obviously, it was Coppola’s artistic decision not to wallow in the horrors that beset Antoinette’s final years, but that same lack of focus about anything other than good times at Versailles mars the rest of the film. Contrary to the figure portrayed here, Antoinette was engaged in the political issues facing her kingdom, particularly late in her reign. But, here’s she seems just a poor-little-rich-party-girl until the merde hits the fan in a big way in 1789. (There are a few scenes involving the French decision to aid the American Revolutionaries, I guess, but they seem unconnected to everything else going on and are in effect shoehorned in.)

Which isn’t to say Marie Antoinette isn’t completely without merit. At times, it — much like The Virgin Suicides, Coppola’s first film — fashions out of the Antoinette story a haunting mediation on the doomed and fleeting transience of youth. (The New Order helps.) And there are several good performances in and around the margins, including Steve Coogan (always threatening to Tristam Shandy at any moment) as the Comte de Mercy-Argenteau and Danny Huston as Emperor Joseph II of Austria (although I do wish he’d thrown in a “hm-hm” to pay homage to Jeffrey Jones.) But, ultimately, this film is just too thin a take on Antoinette’s story to sustain interest over two hours. There’s barely any there there. Even subplots that should be in Coppola’s wheelhouse, given her choice of themes here, seem underdeveloped (most notably Antoinette’s rivalry with Du Barry — It happens, but doesn’t really amount to anything.) And, while the last few shots are undeniably haunting, they can’t justify the long and circuitous route it took to get there. I don’t have a problem with a sympathetic take on Marie Antoinette, per se, but it would’ve been nice to have seen a more fully-developed one.

Magic Most Sinister.

Are you watching closely? I’m having a harder time than usual thinking of what to say about Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige, not only because I think it’s a film best seen cold, with as little information going in as possible, but also because, having read the book by Christopher Priest, my experience with the film was very different from that of most folks. As Michael Caine’s ingenieur Cutter notes at one point, successful magic is all about confusion and misdirection — if you know how it’s done, even a complex and fantastic magic trick can seem blatantly obvious from the get-go. So my time with The Prestige was roughly akin to seeing The Sixth Sense and knowing Bruce Willis is a ghost from the first reel. That being said, while I can’t vouch for how well Nolan conceals his own prestiges from the audience here, I found the movie a dark, clever, and elegant contraption, one that suggests razor-sharp clockwork gears and threatening pulses of electrical current, all impressively encased in burnished Victorian-era mahogany. If you’re a fan of Nolan’s previous work, or of sinister mind-benders in general, The Prestige is a must-see film. Either way, it’s among the top offerings of 2006 thus far.

Are you watching closely? I’m having a harder time than usual thinking of what to say about Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige, not only because I think it’s a film best seen cold, with as little information going in as possible, but also because, having read the book by Christopher Priest, my experience with the film was very different from that of most folks. As Michael Caine’s ingenieur Cutter notes at one point, successful magic is all about confusion and misdirection — if you know how it’s done, even a complex and fantastic magic trick can seem blatantly obvious from the get-go. So my time with The Prestige was roughly akin to seeing The Sixth Sense and knowing Bruce Willis is a ghost from the first reel. That being said, while I can’t vouch for how well Nolan conceals his own prestiges from the audience here, I found the movie a dark, clever, and elegant contraption, one that suggests razor-sharp clockwork gears and threatening pulses of electrical current, all impressively encased in burnished Victorian-era mahogany. If you’re a fan of Nolan’s previous work, or of sinister mind-benders in general, The Prestige is a must-see film. Either way, it’s among the top offerings of 2006 thus far.

So, what’s the pledge? Slumming aristocrat Robert Angier (Hugh Jackman) and working-class upstart Alfred Borden (Christian Bale, particularly good) both serve as magician’s assistants to a by-the-numbers prestidigitator (Ricky Jay) — they’re audience plants — and both harbor aspirations of taking their own act on the road. But after an on-stage tragedy involving Angier’s escapist wife (Piper Perabo), a wedge is driven between these two would-be men of magick, fomenting a lifelong rivalry that turns increasingly brutal and obsessive. This becomes particularly so after Borden, the more talented illusionist, comes up with a nifty trick — The Transported Man — that Angier, the more impressive showman, can’t seem to match, even with the aid of his longtime ingenieur, Cutter (Caine). Eventually, Angier is compelled to travel to faraway Colorado Springs to pay visit to a wizard of a different order, Nikola Tesla (David Bowie), and perhaps enlist him (and his Igor-by-way-of-Brooklyn assistant, (Andy Serkis)) in unraveling Borden’s secret. (As apparently required by law this year, Scarlett Johansson also factors in the tale as Olivia, a lovely magician’s assistant bandied back and forth by the two rivals, but it’s a smaller part than you might expect, and newcomer Rebecca Hall makes more of an impression as Borden’s long-suffering wife, Sarah.)

So, what’s the pledge? Slumming aristocrat Robert Angier (Hugh Jackman) and working-class upstart Alfred Borden (Christian Bale, particularly good) both serve as magician’s assistants to a by-the-numbers prestidigitator (Ricky Jay) — they’re audience plants — and both harbor aspirations of taking their own act on the road. But after an on-stage tragedy involving Angier’s escapist wife (Piper Perabo), a wedge is driven between these two would-be men of magick, fomenting a lifelong rivalry that turns increasingly brutal and obsessive. This becomes particularly so after Borden, the more talented illusionist, comes up with a nifty trick — The Transported Man — that Angier, the more impressive showman, can’t seem to match, even with the aid of his longtime ingenieur, Cutter (Caine). Eventually, Angier is compelled to travel to faraway Colorado Springs to pay visit to a wizard of a different order, Nikola Tesla (David Bowie), and perhaps enlist him (and his Igor-by-way-of-Brooklyn assistant, (Andy Serkis)) in unraveling Borden’s secret. (As apparently required by law this year, Scarlett Johansson also factors in the tale as Olivia, a lovely magician’s assistant bandied back and forth by the two rivals, but it’s a smaller part than you might expect, and newcomer Rebecca Hall makes more of an impression as Borden’s long-suffering wife, Sarah.)

In keeping with Nolan’s usual m.o., The Prestige is not told linearly, but in narrative fragments spurred by memory, sadness, or anger. In fact, the film begins near the end, with Borden first witnessing and then on trial for the apparent murder of Angier. (Well, that is, after a striking title shot of top hats piled up bizarrely in a forest bed, a shot which makes more sense as the story progresses — I’ll admit to being a sucker for films that start off thus.) And, while the film takes a few jags away from Priest’s book (including omitting both the framing device — good choice — and the very last sequence, which I thought was deliriously creepy and somewhat missed here), it nevertheless keeps the basic story arcs of the novel intact. (In other words, and while remaining as oblique as possible, mystery purists may feel somewhat cheated by the Tesla turn the story takes ninety minutes in, but it’s central to the source material, and had to be there.) Also like the book, Nolan’s final hole card is a deeply disturbing one that’ll linger in the senses well after this trick is complete. In sum, along with Memento and Batman Begins, this jagged tale of illusion and obsession should only add to Chris Nolan’s burgeoning prestige: Bring on The Dark Knight.

In keeping with Nolan’s usual m.o., The Prestige is not told linearly, but in narrative fragments spurred by memory, sadness, or anger. In fact, the film begins near the end, with Borden first witnessing and then on trial for the apparent murder of Angier. (Well, that is, after a striking title shot of top hats piled up bizarrely in a forest bed, a shot which makes more sense as the story progresses — I’ll admit to being a sucker for films that start off thus.) And, while the film takes a few jags away from Priest’s book (including omitting both the framing device — good choice — and the very last sequence, which I thought was deliriously creepy and somewhat missed here), it nevertheless keeps the basic story arcs of the novel intact. (In other words, and while remaining as oblique as possible, mystery purists may feel somewhat cheated by the Tesla turn the story takes ninety minutes in, but it’s central to the source material, and had to be there.) Also like the book, Nolan’s final hole card is a deeply disturbing one that’ll linger in the senses well after this trick is complete. In sum, along with Memento and Batman Begins, this jagged tale of illusion and obsession should only add to Chris Nolan’s burgeoning prestige: Bring on The Dark Knight.

Bumpy Departure.

As far as remakes go, The Departed, Martin Scorsese’s sprawling, overstuffed Boston-area reinterpretation of Andy Lau and Alan Mak’s Infernal Affairs, is by no means an embarrassment. Packed with likable actors delivering quality performances (another hambone turn by Jack Nicholson notwithstanding), it’s a breezy and enjoyable two and a half hours of cinema, and it hits most of the beats of the original decently well. (Maybe too well. A little more deviation from IA might’ve helped in the suspense department.) Still, I left the theater somewhat disappointed, and am a bit surprised by the critical acclaim Departed is getting. For all the sleek direction, actorly firepower, and Mamet-ish wit on display here can’t disguise the fact that Infernal Affairs was a clearly better film — leaner and more nuanced, more elegiac and resonant. Lacking the emotional power of the original, The Departed basically just feels like a well-crafted but hollow genre exercise (that is, when it doesn’t feel like a Nicholson stunt.) And, as far as well-crafted genre exercises go, I think I might’ve preferred Inside Man.

The central plot of both films is at once delightfully simple — cop plays robber, robber plays cop — and devilishly complicated. Here, two Southie graduates of the Massachusetts State Police Academy go to work for opposite sides of the law: Bright young overachiever Colin Sullivan (Matt Damon) takes a gig in a top police investigation unit aimed at taking down nefarious crime kingpin Frank Costello (a.k.a. Whitey Bulger a.k.a. The Joker), while troubled screw-up Billy Costigan (Leonardo di Caprio) finds himself, after a stint in the joint, hired muscle in Costello’s organization. But all is not as it seems: As it turns out, Sullivan the cop — bought off by a bag of groceries a few decades earlier — actually works for Costello as a mole on the force, while Costigan the robber has gone deep undercover at the behest of BPD detectives Queenan (Martin Sheen, avuncular and presidential) and Dignam (Mark Wahlberg, aggro and amusing). As it becomes patently clear to both sides of the game that each has a rat in the house, Sullivan and Costello work to flush out their opposite before they get busted (or, in Costello’s case, dismembered.) And, complicating the situation even further (and in a departure from Infernal Affairs), these two nemeses also unknowingly share the love of the same woman, an alluring police shrink (Vera Farmiga) who tends to make really poor life decisions.

All of this is executed competently enough. Scorsese keeps the wheels turning and the tension up throughout, and The Departed benefits from many excellent performances around the margins: Both Wahlberg (easily the most comfortable with the Boston accent, for obvious reasons) and particularly Alec Baldwin (as a grizzled police detective, one-half his character in Glengarry Glen Ross, one-half Sgt. Jay Landsman) are laugh-out loud funny at times, while David O’Hara and Sexy Beast‘s Ray Winstone add sinister depths to Costello’s criminal outfit. And, while most of Mystic River felt more plausible to me, the Boston locale gives The Departed some strong local color that feels fresh and different from the Hong Kong of Internal Affairs. (I particularly liked some of the Irish witticisms. I’d never heard the Freud quote: “This is one race of people for whom psychoanalysis is of no use whatsoever.” And I enjoyed Sullivan’s warning to his psychiatrist girlfriend late in the film, something along the lines of “If this isn’t working, you need to get out. I’m Irish. Something could be wrong, and I’d spend the rest of my life just dealing with it.“)

Both Leonardo di Caprio and Matt Damon do high-quality work too, but here some of my issues with the film emerge. As played by the charismatic Tony Leung of Hero, In the Mood for Love, and 2046, the undercover cop character in Internal Affairs is a resigned, world-weary sort, a guy who seems to carry reservoirs of inexpressible sorrow with him everywhere he goes. But, here, di Caprio is basically a pill-popping panic attack for two hours, cringing and sweating his way through every scene. Fine, that’s a stylistic choice: More problematic is Damon’s character, who’s become considerably less interesting than the conflicted cop played by Andy Lau (of House of Flying Daggers) in the original. For some reason, he’s been stripped down and rendered a much more conventional villain. Damon does what he can, but I preferred the subtler, more pained motivations of Lau’s mole than I do the unctuous, take-no-prisoners careerism they’ve saddled Damon with here.

And then there’s Jack. Nicholson has put in some extraordinary performances in his time, but, as someone put it in another comment thread, he’s been coasting like Pacino for a couple of decades now. And, for some ungodly reason, Scorsese gave Nicholson free rein here to act as crazy as he wants. (Yep, the dildo idea was his.) As a result, Nicholson can’t stop leering and preening to the point of distraction. Whether it be making rat faces, covering his arms in splatterhouse gore, coking out with two prostitutes in the Red Room from Twin Peaks, or generally just acting like he’s seated courtside at the Staples Center rather than running a crime operation, Nicholson just doesn’t work here. Wildly over the top throughout, he’s like a refugee from a sillier, stupider film, and he too often makes The Departed feel little more than a Marty-directs-Jack! casting stunt.

Terry le Heros.

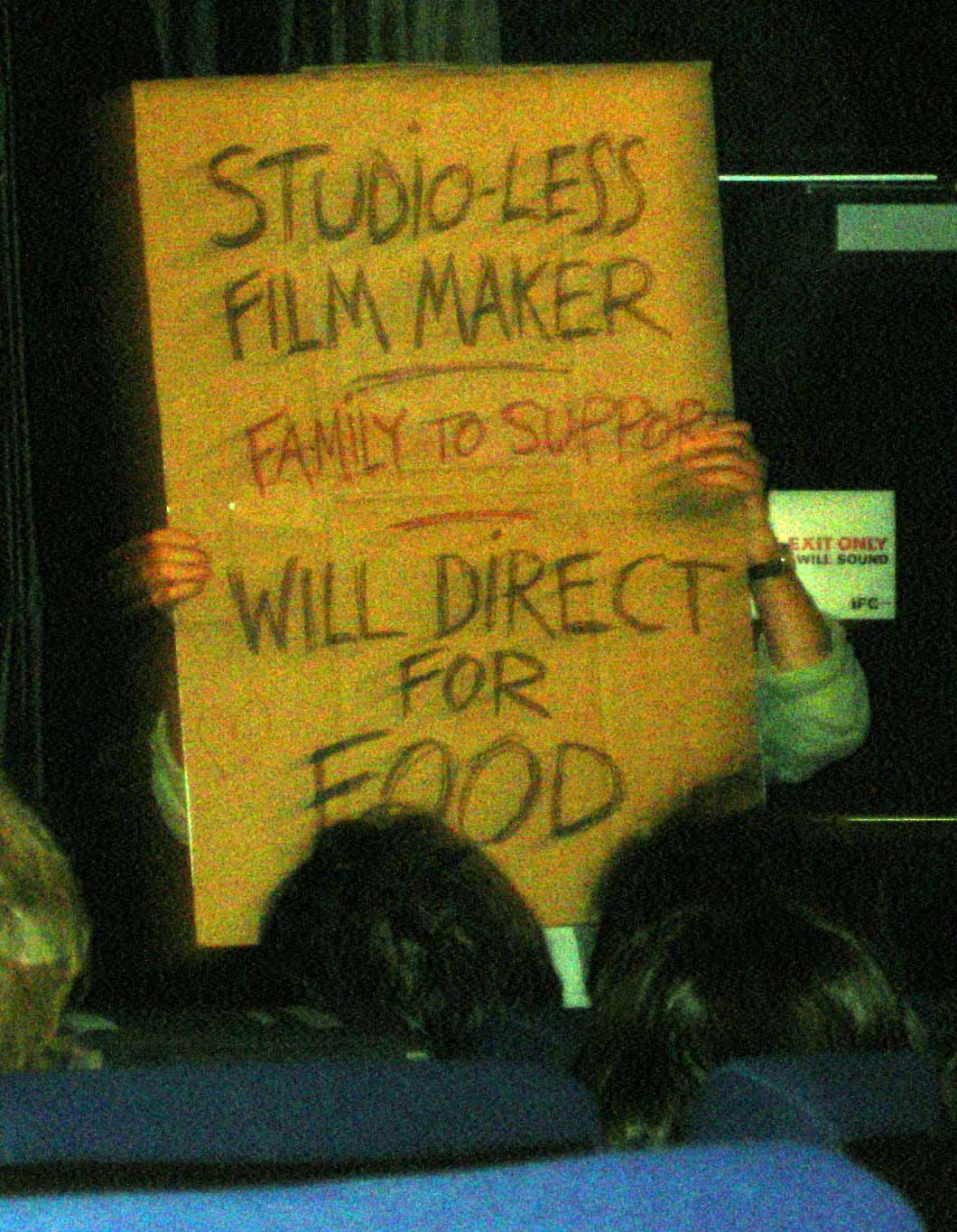

As longtime readers might know (or might’ve adduced from some of the site banners above), I’ve always been a big Terry Gilliam fan, and will pony up for films considerably worse than The Brothers Grimm to repay the man for making Time Bandits, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and one my all-time favorite movies, Brazil. (In fact, “Ghost in the Machine” is the name of this site partly for the Brazil reference.) So it was a real treat yesterday when I and a friend from high school got to see Terry Gilliam live in the flesh last night at the IFC Center on 4th St. After making the rounds in front of The Daily Show yesterday afternoon, Gilliam showed up as part of IFC’s Movie Night series, in which a director of some repute screens one of his favorite films. (In fact, he showed up with the sign he’d been lugging around outside all day: “STUDIOLESS DIRECTOR — FAMILY TO SUPPORT — WILL DIRECT FOR FOOD”) Apparently, Gilliam had wanted to show One-Eyed Jacks, the 1961 western directed by Marlon Brando, but the Brando estate wouldn’t deliver a print or somesuch.

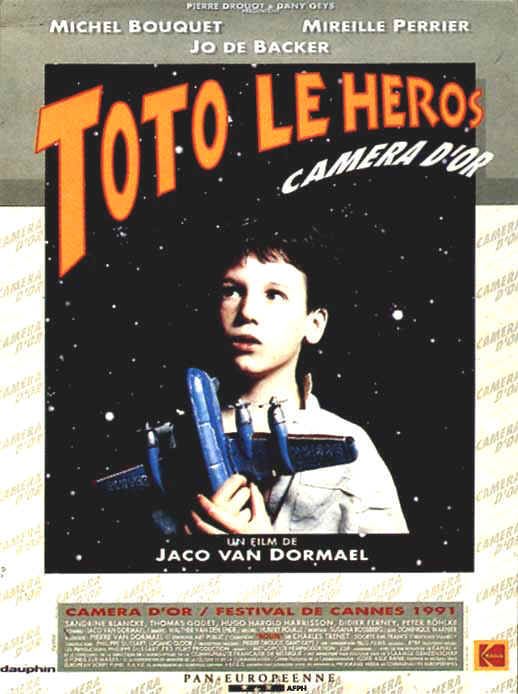

So, the film we got instead was Jaco von Dormael’s Toto le Heros (Toto the Hero), a bizarre Belgian concoction of 1991 that’s part Prince and the Pauper, part Singing Detective, part Citizen Kane and very Gilliamesque. A movie that’s hard-to-explain but that’s definitely worth renting, Toto follows the story of one Thomas van Haserbroeck (Don’t call him van Chickensoup), an imaginative young boy unsettlingly in love with his sister, a lonely man contemplating an affair with a mystery woman, and a deeply depressed senior citizen looking to exact revenge for a life-long grievance. Y’see, Thomas (or Toto, as he’s called in his dream life, where he’s a film noir gumshoe) insists he remembers being switched with another baby — his wealthy next-door neighbor, Albert Kant — during a fire at the hospital, and therein, in his mind, lies the source of most of his troubles. As the story switches back and forth in time, Toto and Albert’s lives keep butting against each other in strange doppelganger fashion, while old-Thomas enacts a plan to reclaim his stolen life…

After the movie, Gilliam returned to the front for a wide-ranging Q&A session, which involved questions both probing (“Did you borrow from Toto in 12 Monkeys?” [No, don’t think so.]) and peculiar (“Where’d you buy your shoes? Where’s the worst place you ever spent the night?” [Birkenstocks, some backwater hut in India]) Along the way, Gilliam told tales of first meeting the Python guys, photographing Frank Zappa in 1967, choosing his various directors of photography, and, the battle of Brazil notwithstanding, generally enjoying the constraints of studio heads and limited budgets. (They focus him.) Speaking of which, he also said Good Omens still seems to be moving forward, and Quixote may still happen someday. (He also mentioned The Defective Detective briefly, but it seemed in the past tense.) And these days he’s digging the new Dylan album, as well The Arcade Fire’s Funeral and The Flaming Lips’ At War with the Mystics.

At one point, he also said he was considering suing Bush, Cheney, et al for making an unauthorized remake of Brazil. With that in mind, I asked him whether his views on Brazil had changed at all now that we’re kinda living it. (I mean, what with Cheney playing Mr. Helpmann, Canadian citizens getting Buttled, and the Dubya team now fully sanctioning Jack Lints, what’s a good Sam Lowry to do, other than await his turn in the chair or on the waterboard?) He noted that, obviously, Brazil-type stuff was going on around the world at the time (in the Soviet bloc, Argentina, etc.) but that he watched the film the other day (to check out the new Criterion HD-DVD version) and was amazed at both how prescient and topical it was.

Throughout, Gilliam was amazingly friendly and personable, and came across a remarkably humble and down-to-earth guy. He kept taking questions well after the IFC-suit tried to close down the affair, and hung around the nearby cafe afterwards to sign various items. I ended up being the second guy in line, and got him to sign the Brazil still above (one of five I have framed in my hallway.) When he asked me my name for the signature, he lit up, “Kevin! Time Bandits Kevin!” I told him I was right around that age when I first saw Time Bandits, and he’s definitely got a lot to answer for.

Beast of Burden.

Unfortunately, the reviews of Stephen Zaillan’s All the King’s Men, the second half of my Friday morning double-feature, are basically correct. The film just doesn’t work…Indeed, it’s even a bit of a stinker. I’ve never seen the 1949 John Ireland/Broderick Crawford version, so I can’t tell you how it compares to that particular Oscar-winner. But, a few ghostly wisps of Penn Warren’s prose notwithstanding, this 2006 take on the novel is, as I feared in a post one year ago today, both hopelessly miscast and remarkably pedestrian. Straining mightily for solemnity throughout its run, this Men feels leaden from the start and fails to capture the sprawling grandeur of the novel (which, I guess, some literary critics hate. I for one love the book — it’s one of my all-time favorites, and not just for the failed historian digression.) If you’ve never read All the King’s Men, trust me — you’ll want to stay away from this flick. (If you have, well, you probably want to stay away too.)

Loosely based on the life of Louisiana’s Huey Long, All the King’s Men follows the trajectory of one Willie Stark (Sean Penn, way off), an earthy and ambitious backcountry politician with big city hungers and national dreams. (Consider him the Tommy Carcetti of his day.) In the midst of running a doomed gubernatorial campaign — designed by political insiders Tiny Duffy (James Gandolfini) and Sadie Burke (Patricia Clarkson) to split the hick vote and thus elect the favored candidate of the powers-that-be — Starr finds his populist voice and manages to capture the State House on a platform of less corporate graft and more roads, schools, and libraries for the people. But, once in office, the lure of power aggravates Stark’s more misanthropic tendencies, and (though this film barely explains how) the new governor begins to enact his redistributive policies with increasingly little regard for democratic niceties.

Along for the ride is our embittered narrator, Jack Burden (Jude Law, also way off but, surprisingly, closer to the mark than Penn). A slumming scion of Louisiana’s elite turned disaffected journalist (and functioning alcoholic), Burden, who relishes playing the world-weary observer, becomes Stark’s right-hand man despite himself. But, involvement, like, power, carries its own price. Soon, to accommodate Stark’s growing political appetites, Burden finds he must not only reenter but betray the past he thought he’d earlier burned away, whether it be by digging up dirt on his magisterial godfather, Judge Irwin (Anthony Hopkins, on autopilot), convincing his best friend (Mark Ruffalo, zombielike) to sign up under Stark’s employ, or allowing his youthful sweetheart (Kate Winslet, strangely bad) to herself come under Stark’s thrall.

To the film’s credit, the movie attempts to spend as much time on Burden’s arc as it does on Stark’s, as it should. But the two halves of the tale seem almost wholly separate here — Stark disappears for the middle third, when Burden’s backstory takes center stage. And that’s just the start of what’s wrong here — Simply put, everything just seems off. Penn is wholly unbelievable (and virtually inscrutable) as Stark, Law doesn’t serve much better as Burden. Other actors (Hopkins, Ruffalo) seem bored, others still (Gandolfini, Clarkson) are given too little to do. Accents are consistently mangled throughout. James Horner’s score is intrusive to say the least. Plot details are consistently elided over to the point of the story barely making sense (Why, for example, is Stark being impeached? One gets no clue in this version.) And Zaillan’s hamhanded directing stops the movie dead all too many times (the most egregious case being in the final moments, with the Louisiana seal — you’ll see what I mean.) Even the period is off: The novel takes place during the Depression, but for reasons that never become apparent we begin our tale here in 1954. If it ain’t broke, people…

The sole redeeming grace of this version of All the King’s Men are the occasional literary flourishes from the book, which are usually given by Jude Law in voiceover. Only in these brief moments, and only imperfectly, can we sense the endless jiggers of whiskey, the cedary scent of spanish moss, the lingering sweat and grinding despair that characterize Penn Warren’s novel. Whether it be Willie’s path to power or Jack’s remembrances, All the King’s Men is about more than just a political rise and fall. As befitting its author’s role in the southern agrarian literary movement, curdling at the novel’s heart is a lament for the days of yore and a futile raging against the inexorable indignities of time. The past passes: It marks us forever and can neither be escaped nor reclaimed as it was — it can only be confronted and accepted. “Man is conceived in sin and born in corruption and he passeth from the stink of the didie to the stench of the shroud.” Zaillan’s film version does make a meaningful attempt to capture these crucial elements of the book, but, alas, like Willie himself, its reach far exceeds its grasp.

But it’s of Her I Dream.

Since he’s been on a roll with the exquisite, heartfelt Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (which I thought was far and away the best film of 2004) and the sunny afternoon jaunt Dave Chappelle’s Block Party, which came out earlier this year (I thought less of 2001’s Human Nature), I’ve been very much looking forward to Michel Gondry’s The Science of Sleep. (In fact, I’d say it, The Prestige, The Fountain, Pan’s Labyrinth, and Children of Men were/are probably my most anticipated movies for the remainder of 2006.) Unfortunately, Sleep, which I caught yesterday morning as the first half of a double-feature, was a film I ended up admiring more than truly enjoying. At its best moments, it (like the much better Eternal Sunshine) is a hallucinatory rumination on love, memory, and obsession that’s at turns whimsical and melancholic. But, like scraps of dream exposed to the morning light, these moments are evanescent and fleeting and, without the narrative thrust of Sunshine driving this movie, Science can feel episodic, hit-or-miss, and at times uncomfortably close to twee.

Since he’s been on a roll with the exquisite, heartfelt Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (which I thought was far and away the best film of 2004) and the sunny afternoon jaunt Dave Chappelle’s Block Party, which came out earlier this year (I thought less of 2001’s Human Nature), I’ve been very much looking forward to Michel Gondry’s The Science of Sleep. (In fact, I’d say it, The Prestige, The Fountain, Pan’s Labyrinth, and Children of Men were/are probably my most anticipated movies for the remainder of 2006.) Unfortunately, Sleep, which I caught yesterday morning as the first half of a double-feature, was a film I ended up admiring more than truly enjoying. At its best moments, it (like the much better Eternal Sunshine) is a hallucinatory rumination on love, memory, and obsession that’s at turns whimsical and melancholic. But, like scraps of dream exposed to the morning light, these moments are evanescent and fleeting and, without the narrative thrust of Sunshine driving this movie, Science can feel episodic, hit-or-miss, and at times uncomfortably close to twee.

Like Walter Mitty or Sam Lowry, the shy, imaginative Stephane (Gael Garcia Bernal) lives mostly in his dreams, where he’s the host, star, and in-house band for the psychedelic sitcom/talkshow/mindmeld Stephane TV. In the Paris of the real world, unfortunately, Stephane’s innate inventiveness is rotting away: He wiles the hours at a painfully mundane typesetting job he got through his mother (Miou-Miou), while fending off the bizarre quirks of his coworkers, most notably the middle-aged prankster Guy (Alain Chabat). But, Stephane’s life takes a momentous turn when a piano falls on him during his morning commute, and he meets his striking new neighbor, Stephanie (Charlotte Gainsbourg, daughter of Serge and actress Jane Birkin). After some confusion over whether Stephane prefers Stephanie or her cute friend Zoe (Emma de Caunes), Stephane determines it’s the former in spades, and sets out to win her heart, mainly by appealing to their shared creativity. But, is Stephane’s fanciful dreaming a boon or a burden when it comes to wooing Stephanie? As his real and dream lives begin to fold, splinter, overlap, and convolute, it becomes increasingly harder to tell where he stands with her, or, in fact, where he stands at all.

An occasionally captivating, occasionally baffling exercise in the key of dream-minor, The Science of Sleep gets points for thinking outside the box — note the one-second time machine — and for its unique DIY visual marvels: Plush animals come to life, water taps spew forth cellophane, cardboard cars ride to and fro. (Think of Gondry’s Bjork videos.) And I thought its primary conceit — that the significant other in your head, molded from impressions and fragmentary evidence, desires and wishful thinking, resentments and regrets, is so much more often the one you’re grappling with rather than the actual person — is a shrewd and able one, even if that case was also central to Eternal Sunshine. Finally, the film takes several strange and unexpected turns in its final act, which I appreciated for their attempt to complicate the story here. By the end, both Stephanie and particularly Stephane seem significantly less sympathetic characters, but, even amid all the bizarre dreaming, also in many ways more realistic ones.

An occasionally captivating, occasionally baffling exercise in the key of dream-minor, The Science of Sleep gets points for thinking outside the box — note the one-second time machine — and for its unique DIY visual marvels: Plush animals come to life, water taps spew forth cellophane, cardboard cars ride to and fro. (Think of Gondry’s Bjork videos.) And I thought its primary conceit — that the significant other in your head, molded from impressions and fragmentary evidence, desires and wishful thinking, resentments and regrets, is so much more often the one you’re grappling with rather than the actual person — is a shrewd and able one, even if that case was also central to Eternal Sunshine. Finally, the film takes several strange and unexpected turns in its final act, which I appreciated for their attempt to complicate the story here. By the end, both Stephanie and particularly Stephane seem significantly less sympathetic characters, but, even amid all the bizarre dreaming, also in many ways more realistic ones.

Still, for all the creativity on display, The Science of Sleep feels slack at times, particularly as the lower-caste demons of Stephane’s office perennially return to haunt him. For better or worse, it is dream logic rather than narrative logic which dictates what’s going on throughout Gondry’s film, which can lead to more than a little meandering throughout. In sum, I found The Science of Sleep an intriguing cinematic exercise and even at times a haunting “love” story, but it had definite pacing problems. I definitely recommend seeing it — it’s miles above your traditional rom-com — but it’s less one for the ages (a la Eternal Sunshine) than it is one feverish, uneasy night amid the Dreaming.

Walking on Sunshine.

This’ll probably be a brief one, as, to be honest, the film didn’t make much of an impression. Nevertheless, I caught Little Miss Sunshine earlier this week at the Ward Cinema in downtown Honolulu. Several people I know really dig this movie, so perhaps I went in with unreasonable expectations. Nevertheless, Little Miss Sunshine, while generally warm-hearted and fitfully amusing, showed signs of strain and felt just a bit too self-consciously quirky throughout, as if Todd Solondz cheered up considerably and started writing for television. (In fact, Solondz-lite is a good description of this film — in a way, this feels like Welcome to the Dollhouse, leavened with dollops of artificial good cheer. I prefer my misanthropy neat.) As a result, and through no fault of the consistently excellent cast, I basically ended up just sitting there dutifully throughout Sunshine, neither enjoying myself nor not enjoying myself, until it was over.

This’ll probably be a brief one, as, to be honest, the film didn’t make much of an impression. Nevertheless, I caught Little Miss Sunshine earlier this week at the Ward Cinema in downtown Honolulu. Several people I know really dig this movie, so perhaps I went in with unreasonable expectations. Nevertheless, Little Miss Sunshine, while generally warm-hearted and fitfully amusing, showed signs of strain and felt just a bit too self-consciously quirky throughout, as if Todd Solondz cheered up considerably and started writing for television. (In fact, Solondz-lite is a good description of this film — in a way, this feels like Welcome to the Dollhouse, leavened with dollops of artificial good cheer. I prefer my misanthropy neat.) As a result, and through no fault of the consistently excellent cast, I basically ended up just sitting there dutifully throughout Sunshine, neither enjoying myself nor not enjoying myself, until it was over.

As Sunshine begins, we’re introduced to the various members of the Hoover clan, each of which is as uniquely and identifiably bizarre as, say, the Munsters or the Addams family: Dad (Greg Kinnear) is a relentlessly go-getter (albeit failed) self-improvement guru. Grandpa (Alan Arkin) is a foul-mouthed heroin junkie. Uncle Frank (Steve Carell) is a suicidal Proust scholar. Son Dwayne (Paul Dano) is a disaffected Nietzsche fanatic living out a vow of silence. Like Marge Simpson, Mom (Toni Collette) is the still, calm, and long-suffering center of their world, the only character who doesn’t get her own quirk. And daughter Olive (Abigail Breslin, cute as a button) harbors only one wish: to be crowned a child beauty pageant queen, namely Little Miss Sunshine. When Olive unexpectedly gets the chance to fulfill her desire, the entire family packs into a VW bus with a bothersome clutch and, in the manner of these types of films, embarks on a hijinx-filled road trip, during which much hilarity theoretically ensues.

I don’t want to give away every twist and turn, because that’s pretty much the sum of the film’s entertainment value (although I will note that, by the end, noone will doubt this family’s commitment to Sparkle Motion.) But a number of vignettes do seem to rely on sitcom-like coincidences (for example, the world’s two foremost Proust scholars at the same truck-stop at the same time) that increase the feeling that this film is set in a remote corner of television-land. Like I said, Little Miss Sunshine isn’t a bad film by any means, and I suspect most people will enjoy it more than I did. But, to my mind, there just wasn’t much there there.

Rocky Road.

So the second half of the aforementioned weekend double-feature was Woody Allen’s Scoop. (As far as choices go, we were somewhat limited — other members of our party had already seen Little Miss Sunshine and Talladega Nights, and while I may still catch Snakes on a Plane at some point, I’d like to see it with a bigger, rowdier audience than would fill an afternoon matinee on the islands.) At any rate, cringeworthy at first, Scoop is a passable little flick, I suppose — Once it settles into its rhythm, it’s a decent ninety minutes of air-conditioning. When I say it feels like an old-fashioned throwback, I don’t mean in the sense of vintage Allen comedies like Bananas, Love and Death, Take the Money and Run, or Sleeper. It’s nowhere near as funny as those films, even if Allen is once again doing his usual nebbishy schtick here. (It is, however, better than recent Allen bombs like Manhattan Murder Mystery or Small Time Crooks, albeit not by much.) Rather, with its thin characters and gossamer plot line, Scoop is so breezy as to seem weightless — there’s barely a movie here at all, just an opportunity for Woody and new favorite sidekick Scarlett Johannson to play Woody for an hour and a half. This will likely seem either endearing and nostalgic or deeply painful to you, depending on your threshold for Allenisms.

So the second half of the aforementioned weekend double-feature was Woody Allen’s Scoop. (As far as choices go, we were somewhat limited — other members of our party had already seen Little Miss Sunshine and Talladega Nights, and while I may still catch Snakes on a Plane at some point, I’d like to see it with a bigger, rowdier audience than would fill an afternoon matinee on the islands.) At any rate, cringeworthy at first, Scoop is a passable little flick, I suppose — Once it settles into its rhythm, it’s a decent ninety minutes of air-conditioning. When I say it feels like an old-fashioned throwback, I don’t mean in the sense of vintage Allen comedies like Bananas, Love and Death, Take the Money and Run, or Sleeper. It’s nowhere near as funny as those films, even if Allen is once again doing his usual nebbishy schtick here. (It is, however, better than recent Allen bombs like Manhattan Murder Mystery or Small Time Crooks, albeit not by much.) Rather, with its thin characters and gossamer plot line, Scoop is so breezy as to seem weightless — there’s barely a movie here at all, just an opportunity for Woody and new favorite sidekick Scarlett Johannson to play Woody for an hour and a half. This will likely seem either endearing and nostalgic or deeply painful to you, depending on your threshold for Allenisms.

The set-up is this: Sondra Pransky (Johansson) is a verbose, vaguely neurotic, and bespectacled (you do the math) college journalist staying with upper-class friends in London and aiming to break into the journalistic big-time. While serving as an audience volunteer for a third-rate Borscht Belt magic show one evening by the Great Splendini, a.k.a. Sid Waterman (Allen), Pransky is visited by a ghost in the machine: namely, that of former Fleet Street legend Joe Strombel (Ian McShane, carrying Al Swearingen with him whereever he goes right now). Apparently unable to file his story from the grave, Strombel’s spectre offers Pransky the scoop of a lifetime: upper-crust son of privilege Peter Lyman (Hugh Jackman) is in fact the Tarot Card Killer, a lowlife murderer currently haunting the streets of London. Armed with this unearthly knowledge, Pransky and Waterman set out to get enough dirt on the young Lord Lyman to make the story, a plan which is complicated, naturally, by Pransky falling in love with her target.

The set-up is this: Sondra Pransky (Johansson) is a verbose, vaguely neurotic, and bespectacled (you do the math) college journalist staying with upper-class friends in London and aiming to break into the journalistic big-time. While serving as an audience volunteer for a third-rate Borscht Belt magic show one evening by the Great Splendini, a.k.a. Sid Waterman (Allen), Pransky is visited by a ghost in the machine: namely, that of former Fleet Street legend Joe Strombel (Ian McShane, carrying Al Swearingen with him whereever he goes right now). Apparently unable to file his story from the grave, Strombel’s spectre offers Pransky the scoop of a lifetime: upper-crust son of privilege Peter Lyman (Hugh Jackman) is in fact the Tarot Card Killer, a lowlife murderer currently haunting the streets of London. Armed with this unearthly knowledge, Pransky and Waterman set out to get enough dirt on the young Lord Lyman to make the story, a plan which is complicated, naturally, by Pransky falling in love with her target.

What this all amounts to is Johansson flirting with Jackman and/or playing Nancy Drew while Allen bumbles his way through various upper-class social gatherings. (Allen’s portrayal of the British class system is as cartoonish here as it was in Match Point, but, hey, that’s ok — for all intent and purposes, Scoop is a cartoon.) When Allen delivers seemingly decade-old groaners or fumbles with a goofy mnemonic for entirely too long, Scoop can be hard to watch without gritting your teeth and just grimacing through it. But, occasionally, Allen falls into a comfort zone or delivers a choice line which suggests there’s still some life in Alvy Singer yet. The former moments outweighs the latter, sure, and perhaps I’m being too lenient on Woody here. But, at the very least, Scoop isn’t flat-out terrible like so many other recent Allen comedies, although I can’t recommend anyone actually rush out and spend money on it. (Although, if you do, Buffy fans, keep a sharp eye out for Giles (Anthony Stewart Head) in a very brief supporting role, as well as — more exciting for my purposes — fanboy stalwarts Julian Glover (Empire, Indy 3) and Charles Dance (Alien 3, The Golden Child).)

What this all amounts to is Johansson flirting with Jackman and/or playing Nancy Drew while Allen bumbles his way through various upper-class social gatherings. (Allen’s portrayal of the British class system is as cartoonish here as it was in Match Point, but, hey, that’s ok — for all intent and purposes, Scoop is a cartoon.) When Allen delivers seemingly decade-old groaners or fumbles with a goofy mnemonic for entirely too long, Scoop can be hard to watch without gritting your teeth and just grimacing through it. But, occasionally, Allen falls into a comfort zone or delivers a choice line which suggests there’s still some life in Alvy Singer yet. The former moments outweighs the latter, sure, and perhaps I’m being too lenient on Woody here. But, at the very least, Scoop isn’t flat-out terrible like so many other recent Allen comedies, although I can’t recommend anyone actually rush out and spend money on it. (Although, if you do, Buffy fans, keep a sharp eye out for Giles (Anthony Stewart Head) in a very brief supporting role, as well as — more exciting for my purposes — fanboy stalwarts Julian Glover (Empire, Indy 3) and Charles Dance (Alien 3, The Golden Child).)