All the King’s Men by way of Heart of Darkness (and more than a dash of Hotel Rwanda), Kevin MacDonald’s The Last King of Scotland is a harrowing portrait of the scampish, fun-loving, paranoid, and genocidal Idi Amin, former president/warlord of Uganda, and a moderately engaging cautionary tale about the dangers of seeking to find oneself in a place one doesn’t belong. Somewhat clunkily assembled (despite being co-written by Peter Morgan, screenwriter of The Queen) and suffering from a third act that, like its protagonist, gets lost somewhere amidst its downward trajectory, The Last King of Scotland is a film mostly redeemed by excellent performances — notably Forest Whitaker as Amin and James McAvoy as our (anti-)hero, but also Gillian Anderson, Simon McBurney, and others in supporting roles. It wasn’t quite as good as I was hoping or expecting, but it’s definitely worth a rental — for Whitaker if for nothing else — if you can handle the increasingly graphic carnage of the film’s final hour.

All the King’s Men by way of Heart of Darkness (and more than a dash of Hotel Rwanda), Kevin MacDonald’s The Last King of Scotland is a harrowing portrait of the scampish, fun-loving, paranoid, and genocidal Idi Amin, former president/warlord of Uganda, and a moderately engaging cautionary tale about the dangers of seeking to find oneself in a place one doesn’t belong. Somewhat clunkily assembled (despite being co-written by Peter Morgan, screenwriter of The Queen) and suffering from a third act that, like its protagonist, gets lost somewhere amidst its downward trajectory, The Last King of Scotland is a film mostly redeemed by excellent performances — notably Forest Whitaker as Amin and James McAvoy as our (anti-)hero, but also Gillian Anderson, Simon McBurney, and others in supporting roles. It wasn’t quite as good as I was hoping or expecting, but it’s definitely worth a rental — for Whitaker if for nothing else — if you can handle the increasingly graphic carnage of the film’s final hour.

As the film begins, it’s 1970, and (the fictional) Nicholas Gerrigan (James McAvoy of The Chronicles of Narnia) is a recently-minted doctor and young, debaucherous Scotsman looking for a life less suffocating than the one on the plate before him, taking over the family practice. Choosing Uganda more or less at random (he spins a globe to choose his fate, but not without first exercising some veto power), Gerrigan soon finds himself one of two doctors on hand in an overworked clinic deep in the African hinterlands, where the only fun to be had is making flagrant passes at his colleague’s do-gooder wife (Gillian Anderson).

As the film begins, it’s 1970, and (the fictional) Nicholas Gerrigan (James McAvoy of The Chronicles of Narnia) is a recently-minted doctor and young, debaucherous Scotsman looking for a life less suffocating than the one on the plate before him, taking over the family practice. Choosing Uganda more or less at random (he spins a globe to choose his fate, but not without first exercising some veto power), Gerrigan soon finds himself one of two doctors on hand in an overworked clinic deep in the African hinterlands, where the only fun to be had is making flagrant passes at his colleague’s do-gooder wife (Gillian Anderson).

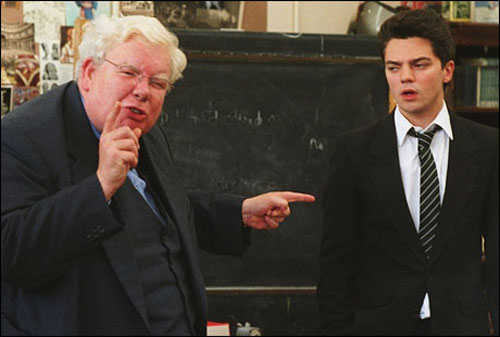

Fate rescues Gerrigan from his ennui, however, in the form of a traffic accident — one which brings him to the attention of Uganda’s new leader, the Scotland-adoring Idi Amin (Whitaker). Soon thereafter, Gerrigan has been made Amin’s personal doctor and “closest advisor,” meaning he spends a lot of time dissolute by the pool, unwittingly (and soon deliberately) oblivious to the bloody machinations holding Amin’s regime in power. That is, until his own somewhat-inadvertent complicity in a murder — as well as some really poor life decisions — force Gerrigan to confront the monstrosities laid before him. This place is a prison, he soon discovers, and these people very clearly aren’t his friends.

As it almost had to be, The Last King of Scotland is most enjoyable in its first hour, as Gerrigan is slowly seduced by the life Amin offers him, and all the sultry pleasures therein included. When it all turns on him, and Gerrigan discovers the heavy price of his fool’s paradise, the film quickly descends into a hell that’s not only hard to watch (one grisly scene brought back unsettling childhood memories of watching…I think it was A Man Called Horse — you’ll know it when you see it) but also somewhat repetitive. How many slo-mo shots of a druggy and/or horrified Gerrigan set to acid-rock do we really need here? Moreover, the film telegraphs one of the good doctor’s key indiscretions for far too long — at least forty minutes is spent simply waiting for the other shoe to drop, so to speak.

As it almost had to be, The Last King of Scotland is most enjoyable in its first hour, as Gerrigan is slowly seduced by the life Amin offers him, and all the sultry pleasures therein included. When it all turns on him, and Gerrigan discovers the heavy price of his fool’s paradise, the film quickly descends into a hell that’s not only hard to watch (one grisly scene brought back unsettling childhood memories of watching…I think it was A Man Called Horse — you’ll know it when you see it) but also somewhat repetitive. How many slo-mo shots of a druggy and/or horrified Gerrigan set to acid-rock do we really need here? Moreover, the film telegraphs one of the good doctor’s key indiscretions for far too long — at least forty minutes is spent simply waiting for the other shoe to drop, so to speak.

That being said, Forrest Whitaker’s performance here makes up for a lot of mistakes. (Seeing the clearly quiet-natured Whitaker’s shellshocked acceptance speech at the Globes last weekend made his work here seem all the more surprising and impressive.) The Willie Stark last year’s All the King’s Men desperately needed, Whitaker commands the camera in every scene he’s in — His Amin is all the more horrifying because he’s basically an overgrown boy, all appetite and no restraint. In every scene, you can sense him lumbering somewhere on the border between childish glee and murderous rage, and we never know where the axe will fall…only that, when it does, it’s not going to be pretty.