“The defendant’s effort to make history in this case by seeking 277 PDBs in discovery — for the sole purpose of showing that he was ‘preoccupied’ with other matters when he gave testimony to the grand jury — is a transparent effort at ‘greymail.‘” Plamegate prosecutor Patrick Fitzgerald — whose investigation is continuing — tries to put a stop to Scooter Libby’s shady defense tactics. “‘Graymailing’ — a tactic used to varying degrees by defendants in the Iran-Contra scandal of the 1980s — occurs when a government official charged with a crime demands access to large quantities of classified material in an attempt to force prosecutors either to put national security at risk by producing the material or put the prosecution at risk by allowing the defendant to argue that he can’t get a fair trial without it.”

Category: History

Dixieland.

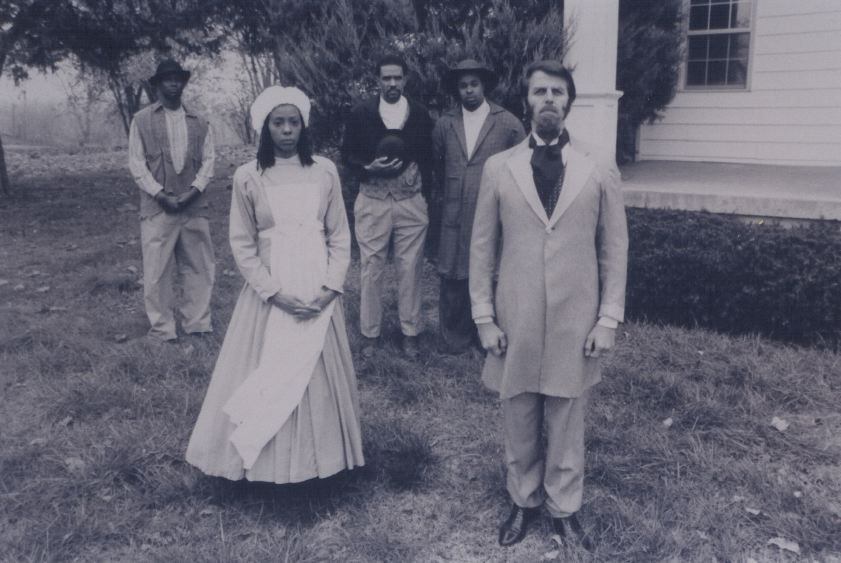

“If you are going to tell people the truth, you’d better make them laugh. Otherwise they’ll kill you.” This savvy George Bernard Shaw quote introduces Kevin Willmott’s razor-sharp documentary-satire C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America, which opened at the IFC Center tonight (followed by a Q&A), and, by that measure, Willmott’s film is a rousing success. At times both blisteringly funny and quietly devastating, C.S.A is a take-no-prisoners alternate history of our Confederacy — Yep, the South won — done in the style of Ken Burns’ The Civil War (or Andy Bobrow’s Old Negro Space Program), right down to bizarro versions of Shelby Foote and Barbara Fields. Punctuated throughout by offbeat television commercials that are eerily similar to today’s TV, C.S.A. is one of the best (and most ruthless and unflinching) satires I’ve seen in some time. And it illuminates a central fact often obscured in so many Brother-against-Brother tributes to America’s bloodiest conflict (as well as drek like Gods and Generals): The Civil War was begun and fought over slavery. In the words of C.S.A. Vice-President Alexander Stephens — in his inaugural address, no less — the Confederacy was founded “upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery –subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition.“

“If you are going to tell people the truth, you’d better make them laugh. Otherwise they’ll kill you.” This savvy George Bernard Shaw quote introduces Kevin Willmott’s razor-sharp documentary-satire C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America, which opened at the IFC Center tonight (followed by a Q&A), and, by that measure, Willmott’s film is a rousing success. At times both blisteringly funny and quietly devastating, C.S.A is a take-no-prisoners alternate history of our Confederacy — Yep, the South won — done in the style of Ken Burns’ The Civil War (or Andy Bobrow’s Old Negro Space Program), right down to bizarro versions of Shelby Foote and Barbara Fields. Punctuated throughout by offbeat television commercials that are eerily similar to today’s TV, C.S.A. is one of the best (and most ruthless and unflinching) satires I’ve seen in some time. And it illuminates a central fact often obscured in so many Brother-against-Brother tributes to America’s bloodiest conflict (as well as drek like Gods and Generals): The Civil War was begun and fought over slavery. In the words of C.S.A. Vice-President Alexander Stephens — in his inaugural address, no less — the Confederacy was founded “upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery –subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition.“

To kick off its conceit, C.S.A requires that you make two leaps of logic from the history of the Civil War: First, that, after the Emancipation Proclamation is issued, C.S.A. Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin managed to convince England and France to join the war on the side of the Confederacy. (This was less likely, I think, than the film makes it out to be. Popular support in England — who had abolished slavery in 1833 — was pretty clearly on the side of the Union, particularly after Lincoln’s Proclamation, and “King Cotton diplomacy” just wasn’t going to work when England and France could import cotton instead from India, Egypt, and other waystations in their respective empires. And, even if the European powers had recognized the CSA, which they might’ve done had the South won more battles, they weren’t about to send troops across the Atlantic to fight on the side of slavery without severe popular repercussions.) Second, and more unlikely, is that, after capturing Washington DC, the South managed to subdue and annex the entire North, leveling Boston and Philadelphia (a la Sherman’s March) in the process. Even despite the Union’s hold on the Mississippi in the Western theater, the South might well have won the war, if Northern public opinion had collapsed in 1863 and 1864 (As it was, timely Union victories — and particularly the fall of Atlanta — buoyed Lincoln’s reelection.) But, had that happened, IMHO, there would likely be two nations uneasily living side by side for decades to come, as you find in Harry Turtledove’s How Few Remain series.

Ok, all that history geekery notwithstanding (which is somewhat unfair to the movie — it’s an alternate history satire, after all, which also explains the more recognizable battle flag replacing the official Stars and Bars on the moon and elsewhere), once you make the conceptual leap that the Confederacy managed to win the war and annex the Union, the rest of C.S.A is remarkably well-thought-out, and at times even scarily plausible. Like Jeff Davis, Lincoln is captured trying to escape in costume (on the Underground Railroad) and sent to Fort Monroe — Here, it’s dramatized in the 1915 D.W. Griffith film, The Hunt for Dishonest Abe. While the South contemplates various “Reconstruction” plans to reintroduce slavery to the North (and Nathan Bedford Forrest reenacts Fort Pillow over and over again), William Lloyd Garrison leads an abolitionist/transcendentalist contingent to Canada. Rather than the Chinese Exclusion Act, the C.S.A. passes a “Yellow Peril Mandate” providing for the enslaving of Chinese laborers. And, as in our world, the nation comes together again to fight a (here much broader) Spanish-American War.

As we get to the 20th century, C.S.A. continues to adroitly riff on American history. Audiences swarm to the Civil War musical, A Northern Wind. (“You tried to take my blacks, But I still want you back.“) In WWII, the C.S.A. plays nice with Germany while despising Japan. (Thanks to the service of Judah Benjamin, Jews can still live in the Confederacy, provided they stay on their “reservation” in Long Island.) Eventually, an armed, highly defended border — the “Cotton Curtain” — descends between Canada and the C.S.A., and ’50’s Confederates scour the nation for the “Abs” (abolitionists) in their midst. Later still, slave riots break out in Newark, Watts, and elsewhere in the turbulent ’60s, as many white Confederates reconsider slavery (due to global sanctions, give or take South Africa) and women begin to demand the vote.

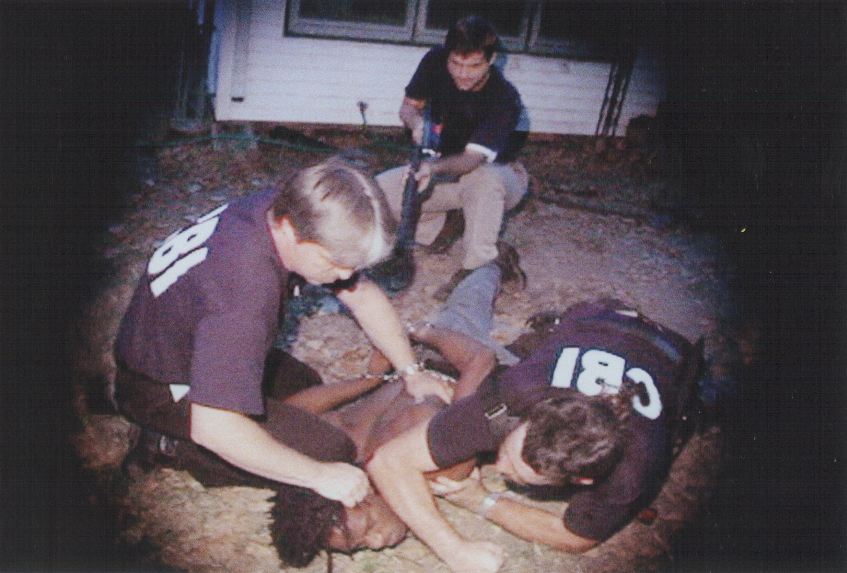

Equally as nimble as the mirror-image counterhistory of the CSA are the many commercial breaks throughout the fake documentary, with ads that are both jaw-droppingly brazen and laugh-out-loud funny. (You can get a sense of this from the trailer — Think Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, itself an excellent satire, to the nth degree.) They range from fake ads for unfortunately real products (Darky Toothpaste, Coon Chicken Inn) to all-too-possible modern innovations — The Slave Shopping Network, a LoJack “Shackle”, a Claritin-ish drug to treat drapetomania (the runaway disease “discovered” by Dr. Samuel Cartwright in 1851), a COPS-style show called RUNAWAYS, etc. etc. As you can see, this is withering stuff, and some might find it in horrible taste. But, there’s method to CSA’s madness. As I noted before, we tend to do a pitiful job of facing up to slavery, America’s Original Sin, and for ninety hilarious, cringeworthy minutes, CSA forces us to look the peculiar institution square in the eye. If we’re serious about our proclaimed role as a Beacon of Freedom to the world, that’s something we need to start doing a lot more often. (But, don’t worry — C.S.A. sweetens this tonic with quite a few laughs.) At any rate, if it’s anywhere near you, definitely go check it out.

Plot Foiled.

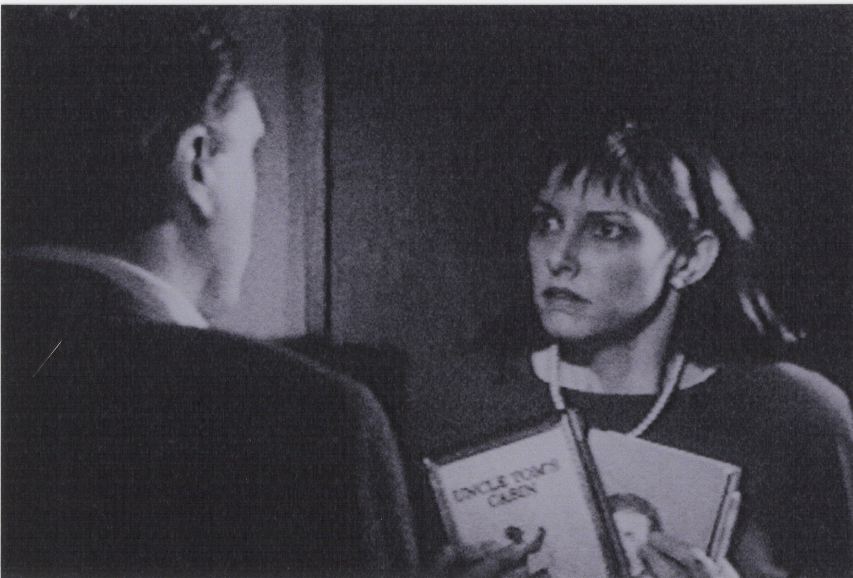

A quick book bash: I wasn’t going to write about Philip Roth’s The Plot against America, which I read a few weeks ago, until seeing C.S.A tonight crystallized my problems with it. I should say up front that I run hot and cold on Roth — I quite liked Portnoy and American Pastoral, but kinda loathed Goodbye, Columbus. And, while The Plot Against America is getting good reviews all around, I had a strongly adverse reaction to it. For those of you who haven’t heard anything about it, Plot describes an alternate USA in which famed aviator and rabid isolationist Charles Lindbergh defeats FDR in 1940, makes peace with Hitler, and begins a pogrom of sorts against Jewish-Americans, forcibly enrolling Jewish children (including the narrator’s brother) in Americanization programs and, eventually, attempting to relocate Jewish families to the Midwest. As per Roth’s usual m.o., the tale is told from the perspective of a Newark family trying to find their way — not very successfully — amid the deteriorating events.

As alternate histories go, it’s a great idea for a book, and I was really looking forward to seeing what Roth did with it. But, unlike CSA, which clearly showed an attentiveness to both what happened and what might have happened, Roth here has written an alternate history without seeming to give a whit about the history. In short, I found the book stunningly, almost narcissisticly, myopic. One gets the sense from reading Plot that the rift beween Jews and Gentiles in America was not only the most significant but the only ethnic or cultural schism in FDR’s America. This is not to say anti-semitism wasn’t rampant and widespread at the time — Of course it was, as attested by Father Coughlin, Breckinridge Long, and Lindbergh himself, who — in a speech that tarnished his reputation much more than Roth lets on — blamed support for the war on the “large ownership and influence [of Jews] in our motion pictures, our press, our radio, and our Government.” But, in The Plot Against America, no one else seems to even exist besides Jews and (White) Gentiles — To take the two most notable examples, there’s no mention of the fact that Africans-Americans were being lynched in staggering numbers in this period (the only lynching mentioned is that of Leo Frank), or that we actually did intern Japanese-Americans during the war. (As a point of contrast, C.S.A.‘s central thesis is about slavery, but it moves beyond white-black relations to explore, or at least reference, the place of Asians, Latinos, and gay Americans in the new Confederate system.)

This isn’t about tokenism — it’s about doing justice to the people and the history of the period you’re writing about. And, frankly, the history in The Plot Against America strains credulity time and time again. I’ll skip over the final twist so as not to give it away, and because it’s so ridiculously implausible that Roth couldn’t have intended for us to take it seriously. But, even despite that, Lindbergh’s popularity — and the public’s taste for isolationism — by 1940 seem significantly overstated throughout. (To take one example, there is no way that the Solid Democratic South would up and vote GOP that year — With the Civil War only recently out of living memory, the Dems could’ve run a wet paper bag in the South, so long as it wasn’t of the party of Lincoln and didn’t threaten to upset the Jim Crow racial order. That didn’t even begin to change until Strom in ’48.) And, while Walter Winchell plays a large role here in calling out the Nazi-American pact and resulting Jewish pogrom, he seems to be the only public figure in America doing so. Where’s everyone else? It doesn’t make sense.

Finally (and I’ll admit, this really ticked me off), Plot basically commits a character assassination of progressive/isolationist Burton Wheeler of Montana, who here appears as Lindbergh’s Vice-President (or, more to the point, his Cheney — I’m assuming that’s what Roth was getting at.) At a certain point in Plot, we’re supposed to believe that Wheeler — a guy who refused to prosecute alleged dissenters as Montana Attorney General during the hysteria of WWI, helped lead the investigation into the government corruption of Teapot Dome, and turned on FDR because he thought court-packing was an unconstitutional powergrab — is going to, out-of-the-blue, declare martial law and start rounding people up? That makes zero sense, and is, in effect, a slander on a real historical figure. Roth is obviously one of America’s most gifted writers — but, lordy, I thought The Plot Against America needed more research, more attention to historical nuance, and more sense that injustice and suffering in this country has often run along more than one axis of discrimination.

Leo Rex.

Looks like Spielberg and Neeson’s Lincoln may have started a welcome trend. Trading in the aviator glasses for pince-nez, Leonardo di Caprio will apparently star as TR in Martin Scorsese’s The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, based on the Edmund Morris biography. Hmm…I can see that, provided the film doesn’t carry too far into the presidential years. Bully for him.

No More Toshi Station / Maeby We’ll Meet Again.

R.I.P. Phil Brown 1916-2006, who withstood the blacklist and is best remembered as Uncle Owen. (He joins Aunt Beru, who passed in 2000 (9/14).) And, also in unhappy news, farewell to the Bluths, who’ve gone the way of all good and tragically misunderstood television families…for now.

NOW for the Future.

“If I am right, the problem that has no name stirring in the minds of so many American women today is not a matter of loss of femininity or too much education, or the demands of domesticity. It is far more important than anyone recognizes…It may well be the key to our future as a nation and a culture.” Betty Friedan, 1921-2006.

“First Lady of Civil Rights.”

“Hate is too great a burden to bear. It injures the hater more than it injures the hated.” Coretta Scott King, 1927-2006. Said Rep. John Lewis today, ““She was the glue that held the civil rights movement together.“

Been in the Storm So Long.

In related news, a site is chosen for the National Museum of African American History and Culture (at 14th and Constitution NW, near the Washington Monument.) As I argued before, some museum along such lines on our nation’s Mall is long overdue.

Fight Club.

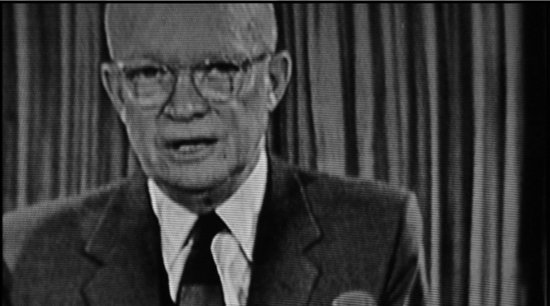

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes.” That flaming liberal Dwight Eisenhower’s somber farewell address to the nation is the historical and thematic anchor for Eugene Jarecki’s documentary Why We Fight, a sobering disquisition on American militarism and foreign policy since 9/11. In essence, Why We Fight is the movie Fahrenheit 9/11 should have been. Like F911, this film preaches to the choir, but it also makes a more substantive critique of Dubya diplomacy and the 9/11-Iraq switcheroo, with much less of the grandstanding that marred Moore’s earlier documentary (and drove right-wing audiences berzerk.)

Sadly, the basic tale here is all-too-familiar by now. Ensconced in Dubya’s administration from the word go, the right-wing think-tank crowd (Wolfowitz, Perle, Kristol, etc.) used the tragedy of 9/11 as a pretext to enact all their neocon fantasies (spelled out in this 2000 Project for a New American Century report), beginning in Iraq. Taken into consideration with Cheney the Military-Contractor-in-Chief doling out fat deals to his Halliburton-KBR cronies from the Vice-President’s office, and members of Congress meekly signing off on every military funding bill that comes down the pike (partly because, as the film points out, weapons systems such as the B-1 or F-22 have a part built in every state), it seems uncomfortably clear that President Eisenhower’s grim vision has come to pass.

To help him rake this muck, Jarecki shrewdly gives face-time not only to learned critics of recent foreign-policy — CIA vet Chalmers Johnson, Gore Vidal (looking unwell) — but also to the neocons themselves. Richard Perle is here, saying (as always) insufferably self-serving things, and Bill Kristol glows like a kid in a candy store when he gets to talk up his role in fostering Dubya diplomacy. (Karen Kwiatkowski, a career military woman who watched the neocon coup unfold within the corridors of the Pentagon, also delivers some keen insights.) And, when discussing the corruption that festers in the heart of our Capitol, Jarecki brings out not only Charles Lewis of the Center for Public Integrity but that flickering mirage of independent-minded Republicanism, John McCain. (In fact, Jarecki encapsulates the frustrating problem with McCain in one small moment: Right after admitting to the camera that Cheney’s no-bid KBR deals “look bad”, the Senator happens to get a call from the Vice-President. In his speak-of-the-devil grimace of bemused worry, you can see him mentally falling into line behind the administration, as always.)

To be sure, Why We Fight has some problems. There’s a central tension in the film between the argument that Team Dubya is a corrupt administration of historical proportions and the notion that every president since Kennedy has been party to an increasingly corrupt system, and it’s never really resolved satisfactorily here. Jarecki wants you to think that this documentary is about the rise of the Imperial Presidency across five decades, but, some lip service to Tonkin notwithstanding, the argument here is grounded almost totally in the Age of Dubya. (I don’t think it’s a bad thing, necessarily, but it is the case.) And, sometimes the critique seems a little scattershot — Jarecki seems to fault the Pentagon both for KBR’s no-bid contracts and, when we see Lockheed and McDonnell-Douglas salesmen going head-to-head, for bidding on contracts. (Still, his larger point is valid — As Chalmers Johnson puts it, “When war becomes that profitable, you’re going to see more of it.“)

Also, the film loses focus at times and meanders along tangents — such as the remembrances of two Stealth Fighter pilots on the First Shot Fired in the Iraq war, or the glum story of an army recruit in Manhattan looking to turn his life around. This latter tale, along with the story of Wilton Sekzer, a retired Vietnam Vet and NYPD sergeant who lost his son on 9/11 and wants somebody to pay, are handled with more grace and less showmanship than similar vignettes in Michael Moore’s film, but they’re in the same ballpark. (As an aside, I was also somewhat irked by shots of NASA thrown in with the many images of missile tests and ordnance factories. Ok, both involve rockets, research, and billions of dollars, but space exploration and war are different enough goals that such a comparison merits more unpacking.)

Nevertheless, Why We Fight is well worth-seeing, and hopefully, this film will make it out to the multiplexes. If nothing else, it’ll do this country good to ponder anew both a president’s warning about the “disastrous rise of misplaced power,” and a vice-president’s assurance that we’ll be “greeted as liberators.”

Slip the Surly Bonds.

In remembrance of STS-51L, a.k.a. the Challenger accident, twenty years ago today.