“The academy never wholly embraced Foote (who, for his part, never considered himself a professional historian or a military expert). Some historians complained that Foote didn’t pay enough attention to the political and economic factors behind the war. Others were offended that he’d dare to write history without footnotes. Looking back, was it merely a case of Northern empiricism scorning Southern charm?” New Yorker editor Field Maloney assesses the historical contribution of — and controversy over — the late Shelby Foote.

Category: Ivory Tower

Unpopular chic.

“If a book is conceived with only historiography in mind — with academic disciplinary debates and research agendas dictating the focus and the form — it’s unlikely to succeed in the public realm. If it’s conceived without historiography in mind, it’s unlikely to succeed as scholarship. So, how do we develop what we might call a Goldilocks approach to historiography?” In a very intriguing two-part article for Slate, David Greenberg of Rutgers University makes the case for historians breaking out of the Ivory Tower.

My friends and colleagues here have heard me rant about this on many opportunities — For all the talk of transnationalism and blurring borders in the field right now, the border between academia and popular history remains rigorously guarded by historians who too often equate accessibility with poor scholarship and second-rate thinking. On many occasions, we’ve been told by visiting scholars — including some very big names — that, for better or worse, we’re fated to do “history-professor history” that will have “no effect” on how Americans see their past.

In short, I find this line of thinking very disquieting. Frankly, writing American history tomes that only a rarefied community of scholars will “get” seems to me a rather sad way to spend a life in the discipline. Whatsmore, it’s no accident that right-wing interpretations of the past, be they neo-con or free-market fundamentalism, for example, tend to gain a wider currency in today’s political climate than left-wing ones do. It’s partly because academics on the right seem to have less qualm about popularizing their ideas for a mass audience (and they’ve got more institutions to disseminate them, but that’s another story.)

I find something profoundly irritating about scholars who claim that “ordinary people” will never understand their ideas, and then go on to complain about the nation’s right-wing drift. While it may be hubris to think that any one scholar’s work will make all that much of a difference, it’s still a worthier goal, to my mind, than composing a work of great theoretical insight that’s completely inscrutable to all but those academic elites similarly ordained in the historical arts.

Strike Addendum.

Regarding yesterday’s strike memo hullabaloo, we found out today on good authority that Provost Brinkley did not write the memo, that it in no way respects his views, and that none of the punitive measures listed therein have a snowball’s chance in Hell of being enacted under this administration. Obviously, in a perfect world, the provost wouldn’t have initialed this internal memo at all, but this information definitely accords better with my sense of what’s going on and with my measure of the man.

The Home Front.

As many of y’all know, despite being a PhD student here at Columbia, I very rarely post about the newsmaking disputes that occasionally roil our campus. (Does it reflect badly on my academic gravitas that I spend more time at GitM discussing national politics, movie trailers, and online Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out knockoffs than ideological dust-ups closer to home? Well, so be it.)

That being said, two links of note. First, in the Financial Times, Ian Buruma — with the aid of one of my colleagues, Moshik Temkin — offers what I thought was one of the more sober-minded summaries I’ve read of the recent MEALAC controversy at Columbia. As he puts it, “racism exists, but not all Israeli policies towards Palestinians, however harsh, are inspired by racism. And…not all criticism of Israeli policies is the result of anti-Jewish prejudice. Yet these are the terms in which modern political debates are increasingly couched..”

Second, regarding the recent one-week graduate student strike on campus (which I voted against, due to concerns not unlike the ones I held last year, but respected by not crossing the picket and reviewing paper drafts from home), The Nation‘s Jennifer Washburn offers a write-up which connects the two buzz issues of unionization and academic freedom and includes an unearthed internal memo, signed by provost (and my dissertation advisor) Alan Brinkley, which suggests possible punitive measures to prevent future strikes.

I’ve already written about this at length on the (no longer) internal grad-student-historian listserv, and don’t really feel like getting into it in depth again here. Suffice to say that, while the document does seem uncharacteristic of Prof. Brinkley (as an aside, it reads like it was written by a member of his staff, although obviously it still carries his imprimatur), I am neither surprised nor all that dismayed by this memo. In the face of our continued strike actions, it seems perfectly appropriate to me for the administration — and the university provost, for that matter — to brainstorm both positive and punitive ways to mitigate future disruptions. All this means is that, come the next strike, it may well be time for the rubber to hit the road, and for graduate students who believe in unionization to make real financial sacrifices for our beliefs, as strikers in any other line of work are forced to do. (Of course, given that none of these proposed measures appear to have been enacted this time around, perhaps not.)

In fact, I think there’s actually a silver lining here for pro-union graduate students. For one, I expect this memo will do more to galvanize the movement than all of last week’s ill-conceived strike. For another, perhaps a heightened sense of what a strike actually constitutes might encourage more out-of-the-box thinking and political calculation by union leadership, rather than the “strike-only, strike-first” ideology that afflicts the upper echelons of our organization at the moment. To use an analogy I’m kinda fond of (for obvious reasons), the only way to get to Mars is by spaceship, but you don’t send it before it’s good and ready. Right now, our Mission Control keeps hitting the launch button before we’ve plotted a trajectory or even built the darned thing.

Update: I’ve since been informed in a personal e-mail that I’m both a “Brinkley apologist” (because I clearly don’t share the vitriol of the Palpatine Unmasked contingent) and a “scab.” (Shouldn’t have looked at those drafts, I guess…) You see, this is exactly why I post about Arthur Dent here much more than I do Columbia inside-baseball. Which reminds me, that Frusion Punch-Out link was via Usr/Bin/Grl.

Of Books and Bears.

A couple of navel-gazing notes from the past few weeks:

* I’ve successfully defended my dissertation prospectus, currently and very drably titled “The Legacy of Reform: Progressive Persistence in National Politics, 1920-1928.” So, now I’m really ABD (All But Dissertation), and all systems are go for my upcoming writing year.

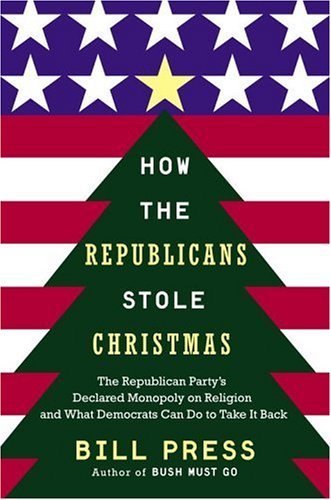

* Although it won’t be out until October, and will require some minor last-minute revisions right up until then (to account for new developments such as the Pope’s probable passing), I’ve spent the past fall and winter researching and editing — and have now finished up — a third collaboration with Democratic commentator Bill Press, entitled How the Republicans Stole Christmas: The Republican Party’s Declared Monopoly on Religion and What Democrats Can Do to Take it Back. In a nutshell (and as you probably guessed from the title), its very timely argument is “The Religious Right is neither religious nor right.” At any rate, since the book is basically in the can and the book cover has made it to Amazon, it seems as good a time as any to tell y’all about it.

* “If you go out in the woods today, you’re in for a big surprise…” Steve Belcher, a high school friend of mine who recently finished a stint at the NY Film Academy — he’s the fellow I was making a few short films with over the winter — has sent along “Sleeping In,” his first very short project, in fabulous Quicktime. Just goes to show, pretty much can anything happen in Central Park these days.

Self-Ordained Professors’ Tongues.

An event of note last night here at Columbia’s Miller Theater: Music critic Greil Marcus, Princeton historian Sean Wilentz, and Oxford poetry scholar Christopher Ricks came together to contemplate Dylania old and new. Marcus began by speaking on the many lives of “Masters of War,” including Dylan’s Gulf War I Grammy performance and the recent “Coalition of the Willing” episode at a Boulder, Colorado high school. Wilentz followed by discussing Dylan’s debts of gratitude (and debt to history) in the recent Chronicles. And Ricks punned his way through a priceless disquisition on Blonde on Blonde and the differences among poetry, prose, and song, finishing his remarks with a defense of “Just Like a Woman,” which apparently has been deemed misogynistic in certain academic corners. (I asked the panel about the mixed reception to Masked & Anonymous, and Wilentz & Marcus in particular praised it as an underrated film…I’ll probably have to see it again at some point.)

All in all, it was quite an interesting evening of Dylanology, although I must admit, I was a bit put off by some of Ricks’ comments in the Q&A session — He called “Masters of War” (and, for that matter, “The Death of Emmett Till“) self-absorbed and overly tendentious songs, which I think there’s a good deal of truth to, but then proceeded to castigate the audience for indulging its generally anti-Bush sentiment (via some mild chuckling) during Marcus’ Coalition of the Willing anecdote. Ricks began by deploring knee-jerk political responses in either direction as a typically American (and occasionally Dylanian) vice…ok, fine, that’s a criticism we’ve all heard before. “Fist fighting is here to stay,

It’s just the old American way.” But Ricks then went on to bemoan the tribulations faced by his poor right-wing friends in Massachusetts, who thought — correctly, in Ricks’ view — that “John Kerry didn’t deserve the presidency.” (As you might expect, this gave the smattering of right-leaning folk amid the audience a chance to clap vociferously and to indulge anew the currently-popular fallacy that they’re an oppressed minority.)

Yes, unfortunately, the decline of civility in debate and the “MacNeill-Lehrerization” of every issue into two opposite and irreconcilable poles are lamentable repercussions of the way politics is practiced today, as Jon Stewart famously noted on Crossfire several months ago. (Or, as Bob once put it, “Lies that life is black and white spoke from my skull…Ah, but I was so much older then,

I’m younger than that now.“) But that doesn’t mean that Americans’ opinions of the war in Iraq aren’t well-thought out and hard-won. Ricks treated the issue as basically six-one, half-dozen-the-other, that to voice an opinion about the Iraq War is somehow irresponsible and — worse — uncouth. (Whatsmore, I had no idea what anybody’s politics were until Ricks began complaining about the presumed incivility in the room, at which point the audience immediately bifurcated into lefties and righties.) In sum, incivility is a serious problem, sure. But, for that matter, so is war.

The Q&A aside, though, the evening made for an eloquent appreciation of the many gifts of Bob Dylan, gifts further illuminated by the warmth and regard with which Marcus, Wilentz and Ricks held these songs to the light and uncovered some of their fragile tendrils of meaning and allusion. And if nothing else, the conference made for an excellent excuse to go home and delve into Bob’s back pages for the remainder of the evening, and listen to old songs with new ears.

Ghosts in the Machine.

“In order to be eligible to teach the classes, you must have: a Ph.D., experience teaching the subject matter, a good teaching record, and an intangible quality that we don’t want to define because we feel that definition would make it tangible. We will pay you roughly $4,000 a class regardless of your experience.” Some academic gallows humor courtesy of The Chronicle of Higher Education: Dear Adjunct Faculty Member. (There’s also a pretty funny piece on the psychological afflictions of grad students making the e-mail rounds, but unfortunately it’s premium content.)

On the Road Again.

Hey y’all…I just got back from last weekend’s escapades, and, poof, I’ll be gone again as of this afternoon. This time it’s off to Boston and Cambridge for some freelance work meetings and dissertation research, with perhaps an hour or two to check out the ole campus environs. At any rate, hopefully I’ll be back here posting again on Sunday. So, until then. Update: I’m back and, other than the ubiquitous, inescapable Red Sox victory gear in every nook and cranny, Beantown and Harvard don’t seem to have much changed since my last trip in ’98. It was nice to see the Square still graced by Tommy’s, the Hong Kong, the Cellar, and most of my other old collegiate haunts.

Radicals of the Republic.

If it’s post-MLK day, it must be the beginning of the spring semester here at Columbia…and this term I’ve returned to America’s shores from East Asia. (How McArthur-esque.) So, for the next few months I’ll be TA’ing “The Radical Tradition in America” for the inimitable Prof. Eric Foner, which I’m greatly looking forward to (despite ending up with Thursday night section times that are less than ideal…but ah well. I can’t blame anyone but myself for that.) Since most of my work this term on the dissertation (on, put very simply, Progressive persistence in national politics, 1919-1928) is going to involve senators, governors, magazine editors, and other inner-circle types (“They sentenced me to twenty years of boredom, for trying to change the system from within“), I’m hoping the objects of study here — individuals and movements working to effect change outside the confining parameters of legislative politics — will make for a nice, dynamic, and thought-provoking counterpoint, and one that will help me shore up my own thoughts on civic republicanism, both in its persistence and its possibilities for renewal.

Blame the Children.

Just as Tom Ridge did in his own resignation a few weeks ago, NASA administrator Sean O’Keefe steps down by citing his need to make more money to put his kids through college. “‘It is this [the president’s] very commitment to family that draws me to conclude that I must depart public service,’ O’Keefe wrote. ‘The first of three children will begin college next fall…I owe them the same opportunity my parents provided for me to pursue higher education without the crushing burden of debt thereafter.’” Am I missing something? I know tuition costs have skyrocketed, but is $158,000-a-year really too little money to send a child to college these days? C’mon, now.