Need a boost to help shake off the winter doldrums? Lots of Co. points the way to this end-of-2006 collection of fun, downloadable mash-ups.

Category: Music

Play a Song for Me.

The freewheelin’ Bob Dylan has a lot to answer for in this intermittently amusing Post Show send-up of Dylan’s No Direction Home. Admittedly, this guy’s singing-Bob impression is pretty funny. (By way of Tes.)

The Band’s Too Big Without You.

Are Sting, Stewart Copeland, and Andy Summer reuniting for a 2007 Police tour? It still sounds pretty speculative in this article, but I’d go, as long as they stick to the classic material and don’t play anything later than Sting’s first, decent solo album. If I see “Fields of Gold” or any of the other easy listening stuff on the setlists, I’m taking a walk (as, I suspect, would Copeland.)

A Carnival of Sorts.

“Gentlemen don’t get caught, cages under cage.” Congrats to Athens’ finest, R.E.M., who will be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame this March, in the first year of their eligibility. The rest of the class of 2007 includes Van Halen, Patti Smith, The Ronettes, and the Hall’s first rappers, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. (By way of WebGoddess.)

Ad Nauseum.

“I’m really sick of celebrities being dug up from their graves to sell us products. I was similarly upset when Gap used the image of deceased rapper Common in a Christmas commercial. (What’s that you say? Common’s still alive? Sorry, but after making that ad, he’s dead to me.)” Old friend Seth Stevenson surveys the worst ads of 2006 for Slate.

Soul man.

“I checked up on the late great J.B., His death is said on national TV…” Alas, James Brown is dead, 1933-2006.

Distant Thunder.

“The pistols are poppin’ and the power is down, I’d like to try somethin’ but I’m so far from town…” Ok, I’ll admit it — I reupped for more time, to catch up on political news. And, while doing so, I discovered that Slate, of all places, is not only premiering Bob Dylan’s new video for Thunder on the Mountain, which is chock-full of vintage Dylan footage, but offering a chance to win a guitar signed by the man himself. Cool…but is it strung lefty?

I’m trying to remember the feeling when the music stopped.

“When U2’s songs weren’t on-the-nose political anthems, they were vague but heroically uplifting — filled with signifiers but signifying nothing. Whereas R.E.M. songs, drenched in Southern detail, allusive and elusive, sounded like fables or folk wisdom, U2’s majestic uplift often felt like the outtakes of a melodically gifted youth-group minister.” Ted of The Late Adopter sends along this side-by-side comparison of R.E.M. and U2 from Slate. I like them both, but, if forced to choose, definitely come down on the R.E.M. side of things. And I’d disagree with this guy’s periodization — I much prefer the most recent R.E.M. album to U2’s last few discs of self-referential “instant-classic-rock,” and thought U2 were actually at their best during their Achtung Baby/Zooropa/Pop experimentation phase. Still, worth a read.

Cate’s in the Well.

Found while looking for an online version of the recent Rolling Stone story on Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There (which includes a shot of Cate Blanchett as the Blonde on Blonde-era Dylan), writer Jonathan Lethem picks out some forgotten Dylan gems as a sidebar to his recent cover story on Modern Times.

Going to the carnival.

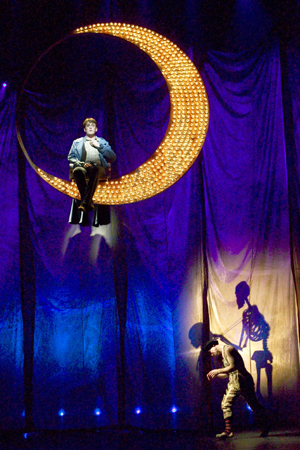

So, my sister, her boyfriend, and I went to check out The Times They Are A-Changin’, the new Twyla Tharp-choreographed reimagining of famous Bob Dylan songs, last Thursday (with, as a star-gazing aside, some heavy-hitters in attendance: Annie Leibowitz sat directly in front of me, and Tharp herself sat directly behind. Yes, I’m a celebrity hound.) And the verdict? Well, first let me say, that — some early dabbling in community-theater notwithstanding — I’m really not much of a musical guy. I tend to find the American Idol-ish histrionics of Broadway singing really distracting, and particularly when the song in question is something like “Masters of War.” Nor have I seen Moving Out, Mamma Mia!, Ring of Fire, Almost Heaven or any of the other “Broadway Karaoke” shows that currently seem to be the rage, so I can’t really compare it to any of the others — I was really more interested to see some intriguing interpretations of Dylan than I was to partake in a group sing-a-long (which, thankfully, Times is not.) With all that said, I found Times to be…kinda hit-or-miss. While some of the visions here do their source material justice in memorable fashion, others fall flat or just seem ill-conceived. And, while the circus acrobatics on display are amazingly well-performed and at times mesmerizing, too many numbers slip into the same dark carnival-of-the-absurd pattern. The cast works hard, but surely, when you get down to it, there is more to Dylan’s oeuvre than just aggro carny folk.

To its credit, Times samples songs from across Dylan’s career, from the hoary (“The Times They-Are A Changin’,” “Blowing in the Wind“) to the obscure (“Man Gave Names to All the Animals,” “Please, Mrs. Henry“), through the lean years (“I Believe in You,” “Dignity“) and up to the recent critical revival (“Not Dark Yet,” “Summer Days.”) Set in a traveling circus run by the vicious, heavy-handed Captain Ahrab (Thom Sesma) — a character from one of Dylan’s great American fables,”Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” not included — the play basically centers around a love triangle among Ahrab, his son Coyote (Michael Arden), and the lady Cleo (Lisa Brescia), one of the circus performers. Through their story — and the larger tale of a power struggle over the circus — are refracted these thirty or so Dylan tunes, strung togther in haphazard but decently compelling fashion.

I’d like to say there’s a formula for when a song works and when it doesn’t, but it doesn’t go over like that. One of the two best numbers, “Simple Twist of Fate” (the only cut from Blood on the Tracks here), is played basically straight. Alone in spotlight, Ahrab sings wistfully in the foreground (as seen at left) while the younger couple cavorts behind him, a haunting memory. “He woke up, the room was bare. He didn’t see her anywhere. He told himself he didn’t care, pushed the window open wide. Felt an emptiness inside, to which he just could not relate.” The bleak, melancholic staging matches the song perfectly, and Ahrab/Sesma channels both its poetry and its pain.

But, in the other most successful number, “Mr. Tambourine Man” (a song I can usually take or leave), Tharp & co. have taken a tune that’s ostensibly about a drug deal and just ran with it. Now, it’s a gripping, Bergmanesque dance of death, with one of the sadder clowns (Charlie Neshyba-Hodges) holding center stage as the ensemble circles around him in black, recalling the doomed pilgrims of The Seventh Seal. Obviously, Tharp isn’t the first to read “Tambourine Man” as a disquisition on mortality. (“I’m ready to go anywhere, I’m ready for to fade…into my own parade, cast your dancing spell my way, I promise to go under it.“) Nevertheless, the staging both feels innovative and cuts close to the bone of the song in surprising fashion.

There are other good moments scattered throughout the show, although few that hold their power over the course of an entire track: For example, a contortionist writhes horribly on a hospital bed during the “Dr. Filth” passage of “Desolation Row,” flashlights whirl and twirl (held by people brandishing them vaguely like tusken raiders) during “Knocking on Heaven’s Door“, the cast memorably get their drink on for “Please, Mrs. Henry,” and one clown reenacts Dylan’s “Subterranean” signage during the latter half of “Like a Rolling Stone.”

But, when a song’s off, it’s pretty off. The most obvious offenders are “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” “Blowing in the Wind,” and arguably “Lay, Lady, Lay,” all of which are performed in a deadly earnest Broadway patter that just stop the show dead. (This is particularly unfortunate in the case of the first one, since that’s how the show begins.) But, there are other problems. The bizarre welcome-to-the-carnival-of-beasties routine works well for “Desolation Row” (since, after all, “The circus is in town“) and maybe even for other rousing numbers such as “Like a Rolling Stone.” But, it’s overdone — in “Highway 61 Revisited,” “Everything is Broken,” “Gotta Serve Somebody,” “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” — to the point that the musical numbers become indistinguishable. (“Masters of War” also falls somewhat into this pattern — I liked it better than most, but was reminded more of ABT’s splendid recent revival of “The Green Table,” which captured the same sentiment better.)

And, sometimes, in my humble opinion, the attempted interpretation falls flat on its face. I thought turning “Not Dark Yet,” Dylan’s gloomy but resigned rumination on death around the corner, into a rage-against-the-dying-of-the-light completely misses the point of the song, which is that he’s given up and given in to the coming darkness. (“I’ve been down on the bottom of a world full of lies. I ain’t looking for nothing in anyone’s eyes.“)

Most egregious in this regard is what’s been done to “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.” Perhaps because it remains such a personal song — a song about two people rather than a generation — I’d say it’s aged much better than almost all of the other hugely popular early-Dylan standards (“Blowing in the Wind,” “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”) In fact, I might go so far as to say that “Don’t Think Twice” may just be the quintessential Dylan break-up song in a career full of them (although now that I write that…Blonde on Blonde, Blood on the Tracks…ok, never mind. That’s too bold a statement.) At any rate, here, all the complexity of competing emotions that drives the track — “I ain’t sayin’ you treated me unkind, you could have done better but I don’t mind, you just kinda wasted my precious time” — is wasted, as it’s become, inexplicably, a number sung by a woman to her overly eager dog. (Although I will concede that the canine in question — I believe it was Jason McDole — was convincingly and creepily Berkeley-like.)

In sum, A Times They Are A-Changin’ is at times engaging, and may be worth catching if you have a hankering for the carnivalesque, if you’re a Dylan completist, or if you have a higher tolerance for showtune renditions than I do. But, as an exploration of Dylanalia, I found the show too narrowly circumscribed within its three-ring circus, and ultimately unsatisfying. (Then again, in the play’s defense, I didn’t think much of Masked and Anonymous either, so perhaps I’m just ornery about such things.)