A New Year is dawning. A New Day is not. I spent the first hour of 2008 watching the first episode of The Wire Season 5 — which is now live if you have HBO On Demand — and it was time very well spent. Between instantly fascinating new characters in the Baltimore Sun newsroom and some even more byzantine connections made between the old regulars (Note Partlow’s errand to the Criminal Court, and wait ’til you see who Herc’s working for), the best show on television is back in a big way. (That being said, it might take me awhile to get used to Mel‘s husband Doug from Flight of the Conchords as the Sun‘s managing editor.) Update; More discussion of Ep. 51 here at Alan Sepinwall’s blog, who’s also compiling a list of The Wire‘s greatest moments (That might take awhile.)

Category: The Wire

Back in the Day.

I heard about these a few days ago and thought they were Youtube fan flicks. But, no, they’re the real deal: Along with the Season 4 DVD comes a handful of exclusive Wire prequels at Amazon.com, including looks at young Omar and Prop Joe in action and Bunk and McNulty’s first bender. Season 5: January 6, or Dec. 31 if you’re On Demand-inclined. (Teasing press-release summaries here.)

It’s All About the Crown.

“I slur when I’m tired, that’s all.” HBO launches new character-specific promos for Season 5 of The Wire, which include brief scenes of Jimmy McNulty, Omar Little, Tommy Carcetti, Marlo Stansfield, and Reginald “Bubbles” Cousins. Avoid like the plague if you’re not yet caught up. (Season 4 comes out on DVD tomorrow.)

The War on Drugs is Lost.

“All told, the United States has spent an estimated $500 billion to fight drugs – with very little to show for it. Cocaine is now as cheap as it was when Escobar died and more heavily used. Methamphetamine, barely a presence in 1993, is now used by 1.5 million Americans and may be more addictive than crack. We have nearly 500,000 people behind bars for drug crimes – a twelvefold increase since 1980 – with no discernible effect on the drug traffic. Virtually the only success the government can claim is the decline in the number of Americans who smoke marijuana – and even on that count, it is not clear that federal prevention programs are responsible. In the course of fighting this war, we have allowed our military to become pawns in a civil war in Colombia and our drug agents to be used by the cartels for their own ends. Those we are paying to wage the drug war have been accused of human-rights abuses in Peru, Bolivia and Colombia. In Mexico, we are now repeating many of the same mistakes we have made in the Andes.“

To their credit, those left-wing hippie radicals at National Review said as much way back in 1996, and HBO’s The Wire has dramatized the dismal consequences of the conflict for several years now. Now, coming to the same dour conclusion in 2007, Rolling Stone‘s Ben Wallace-Wells explains how America lost the War on Drugs, and argues that continuing to perpetuate it in its current fashion — with its “law and order” emphases of crushing supply, international interdiction, and mandatory minimum sentencing — is tantamount to flushing money and lives down the toilet. “Even by conservative estimates, the War on Drugs now costs the United States $50 billion each year and has overcrowded prisons to the breaking point – all with little discernible impact on the drug trade…The real radicals of the War on Drugs are not the legalization advocates, earnestly preaching from the fringes, but the bureaucrats — the cops and judges and federal agents who are forced into a growing acceptance that rendering a popular commodity illegal, and punishing those who sell it and use it, has simply overwhelmed the capacity of government.” (Found via Jack Shafer’s endorsement at Slate.)

Dispatch: Bodymore.

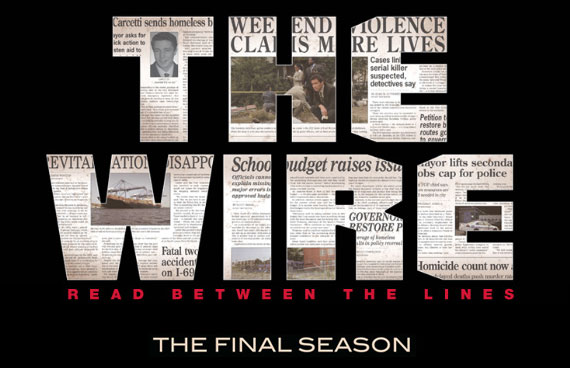

“BALTIMORE, Md. — Crime is up. The drug trade [still] rules the corners. The next election consumes every politician. And McNulty is drinking again.” A new day is [not] dawning: The Wire, Season 5, January 2008.

Little Girl Lost.

Wading into the same dark, turbid, and clannish Boston waters as Mystic River (also by author and Wire contributor Dennis Lehane) Ben Affleck’s Gone Baby Gone is another wicked-smaht tale of horrible crimes and neighborhood secrets in and around the Hub, and marks a promising debut for Affleck as a director (and another step for brother Casey, after The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, towards leading-man status.) The last act unfolds a mite too slowly, I thought, but for the most part Gone Baby Gone — for its ruminations on the meaning (and inescapability) of place as much as its attention to Beantown detail — is an intelligent and gripping crime story that’s worth catching. Affleck, Lehane, and co. are confident enough here to ask tough questions without definitive answers, and it’s those uneasy ambiguities in Gone Baby Gone, as much as the local color, that ultimately sticks with you.

As another day dawns in Dorchester (one of what could be almost any of the white working-class neighborhoods surrounding Boston), Amanda McCready, age 4, is still missing, 72 hours after disappearing from her mother’s unlocked second-floor apartment, and where she is now we can only guess. By this point, the press are having a field day with the abduction story, the police are starting to have doubts about the girl’s survival, and Amanda’s Aunt Bea (Amy Madigan) and Uncle Lionel (Titus Welliver, of Deadwood) are looking to bring flesh blood to the search, namely private investigators Patrick Kenzie (Affleck) and Angie Gennaro (Michelle Monaghan). Kenzie and Gennaro have doubts about taking the case — neither particularly wants to turn up a dead girl — but, as lifelong locals, they know they can find people and go places the badges can’t. In the manner of films immemorial, the police officer in charge of the case (Morgan Freeman) doesn’t take too kindly to these P.I. interlopers on his heels, but assigns them two ornery cop liaisons (Ed Harris and John Ashton) regardless. And, once Kenzie and Gennaro have re-interviewed Amanda’s troubled, hard-partying mom, Helene McCready (The Wire‘s Amy Ryan, giving a Best Supporting Actress-worthy performance) and checked out some of her sketchier haunts, they — sure enough — turn up some new leads in the hunt. But the trail’s growing colder by the minute, and as both P.I.’s know, few child abduction stories ever result in a happy ending — why would Amanda’s be any different?

Dennis Lehane, Amy Ryan, Michael Williams (a.k.a. Omar) appears briefly here as a cop…if I keep making connections here to The Wire, it only speaks in Gone Baby Gone‘s favor. As with that show and Bal’more, this movie relishes its urban environment — this is a Boston story through and through, and that strong sense of place brings the film to life more than anything else. Also like The Wire, Affleck’s film doesn’t refrain from acknowledging that the world is often not a storybook place. (The second act of the movie is particularly dark, and while I thought Affleck perhaps overrelied on aerial establishing shots of Boston and images of “regular” people at times throughout, his delicate handling of this potentially explosive section of the film in particular suggests his potential as a director.)

True, much of what is excellent about Gone Baby Gone must be attributed to Lehane’s book. But, there have been a lot of lousy movies made about excellent books over the years, and if nothing else, Affleck (and his co-screenwriter Aaron Stockhard) have brought Lehane’s story to the screen without sacrificing any moral complexity or narrative momentum. As I said, I think the film lags slightly in the third act (and I do have some issues with Monaghan’s character arc by the end, which I can’t really discuss without giving the film away), but the quietly haunting coda at the end redeemed a lot of those issues for me. The occasional shocks and disruptions notwithstanding, it seems, people are what they are, and life goes on as ever in the old neighborhood.

“The postmodern institutions…those are the indifferent gods.”

“This final season of the show, Simon told me, will be about ‘perception versus reality’ — in particular, what kind of reality newspapers can capture and what they can’t. Newspapers across the country are shrinking, laying off beat reporters who understood their turf. More important, Simon believes, newspapers are fundamentally not equipped to convey certain kinds of complex truths. Instead, they focus on scandals — stories that have a clean moral. ‘It’s like, Find the eight-hundred-dollar toilet seat, find the contractor who’s double-billing,’ Simon said at one point. ‘That’s their bread and butter. Systemic societal failure that has multiple problems — newspapers are not designed to understand it.“

A huge find by way of Chris at Do You Feel Loved?: Margaret Talbot offers a long-form New Yorker profile on David Simon and The Wire. (If you haven’t yet seen Season 4, I recommend bookmarking this for now — it gives away many of S4’s major beats.) There’s also a good deal of spoilerish information on what to expect from Season 5, what David Simon wants to do next, and who’s singing this season’s version of “Way Down in the Hole.” (I’ll give that one away…Bubbles’ sponsor, Steve Earle — listen here.) “Simon makes it clear that the show’s ambitions were grand. ‘”The Wire” is dissent,’ he says. ‘It is perhaps the only storytelling on television that overtly suggests that our political and economic and social constructs are no longer viable, that our leadership has failed us relentlessly, and that no, we are not going to be all right.’”

All in the Game.

“In a way, it doesn’t make sense to talk of ‘The Wire‘ as the best American television show because it’s not very American. The characters in American popular culture are rarely shown to be subject to forces completely beyond their control. American culture is fundamentally Romantic, individualistic and Christian; when it’s not exhorting you to ‘follow your dream’ it’s reassuring us that in the eleventh hour, we will be saved. American culture is a perpetual pep talk, trafficking in tales of personal redemption and the ultimate triumph of good over evil. We don’t do doom. ‘The Wire’ is not Romantic but classical; what matters most in its universe is fulfilling your duty and facing the inexorable with dignity.” From the bookmarks, Salon‘s Laura Miller extols the classical virtues of The Wire. What she said.

Bal’more farewell | Plug in!

“At 4:40 a.m., the assistant director called out, ‘It’s a wrap, it’s a wrap. We’re done. Forever.'” As birddogged by Listen Missy, David Simon & co. have wrapped shooting on the final season of The Wire (and NY Magazine parses the news for hints of what’s to come.) Do I need to say it again? If you don’t watch The Wire, you really, really, really should…from the beginning. I don’t know a single person who has watched the show and not become resolutely evangelical about it. Season 5 doesn’t air until January, so that’s plenty of Netflix time (1, 2, 3, 4) between now and then: “From the beginning when the show debuted in 2002, [Simon] saw it as a visual novel, with each season a distinct chapter exploring an aspect of inner-city life: The first season examined the drug trade; the second focused on Baltimore’s longshoremen; the third grappled with politics and the notion of reform; the fourth dug into education and the lives of the city’s children. This season, which begins airing Jan. 6, explores the media, featuring a morally challenged reporter played by Tom McCarthy, who wrote and directed the indie film ‘The Station Agent.‘”

McNulty, Bunk, Freamon…Heaton.

It played its part against the Barksdale operation in Baltimore. Now it seems an undercover wire may have helped bring down GOP rep and Abramoff flunky Bob Ney. “‘Heaton’s substantial assistance in the investigation and prosecution of Ney was critical to Ney’s decision to admit his involvement in the corrupt relationship with Abramoff,’ Butler wrote. ‘The tapes made by Heaton captured important circumstantial evidence that statements Ney had made to others about matters material to the investigation were false or intentionally misleading.’“