In David Fincher’s Zodiac, well-intentioned cops from different jurisdictions conduct archival sleuthing and the occasional phone trace to track down a cold-blooded killer. But, in Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s powerful, humanistic The Lives of Others, the second half of my double-feature last Friday, the bureaucratic machinery of the State grinds into gear for a darker purpose. Here, in the final flower of Erich Honecker’s East Germany, the Stasi keep their eyes and ears on those who would threaten the integrity of the German Democratic Republic, which, sadly, counts as just about everyone. I know very little about this subject, so I can’t vouch for how well van Donnersmarck recreates the rigors of East German life in the 1980s. Still, as an Orwellian parable of secrets and surveillance, The Lives of Others is a very worthwhile film, one strong enough to overcome some perhaps overly cliched moments of awakening by various characters along the way.

In David Fincher’s Zodiac, well-intentioned cops from different jurisdictions conduct archival sleuthing and the occasional phone trace to track down a cold-blooded killer. But, in Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s powerful, humanistic The Lives of Others, the second half of my double-feature last Friday, the bureaucratic machinery of the State grinds into gear for a darker purpose. Here, in the final flower of Erich Honecker’s East Germany, the Stasi keep their eyes and ears on those who would threaten the integrity of the German Democratic Republic, which, sadly, counts as just about everyone. I know very little about this subject, so I can’t vouch for how well van Donnersmarck recreates the rigors of East German life in the 1980s. Still, as an Orwellian parable of secrets and surveillance, The Lives of Others is a very worthwhile film, one strong enough to overcome some perhaps overly cliched moments of awakening by various characters along the way.

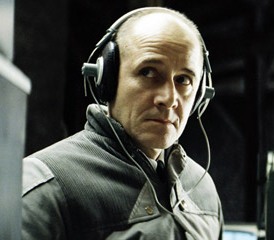

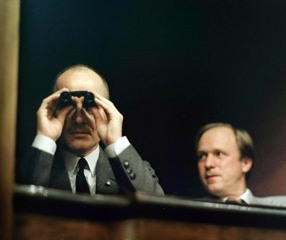

When we first meet Capt. Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Muhe), with his sleek dome, thin ties, and retrofuturistic jacket, he’s training young Stasi cadets in the subtler techniques of interrogation and threatening landladies with the ruin of their children’s future — clearly a right rotten bastard of the first order. Still, there’s something undeniably impressive about the ever watchful Wiesler, a man who’s both cognizant of even the slightest emotional shifts in his prey and committed fully to the ideological aspirations of the Party. Wiesler’s skill and fervor is not lost on party flunky Anton Grubitz (Ulrich Tukur), who assigns him to a career-making case of digging up dirt on the roguishly handsome, go-along-to-get-along playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) for a well-connected romantic rival.

But, something — perhaps the sight of Dreyman’s beautiful actress girlfriend Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck) on stage, perhaps something else — clicks in Wiesler as he conducts his round-the-clock surveillance. And, from the dismal attic above Dreyman’s apartment, Capt. Wiesler soon begins, despite himself, to commit Thoughtcrime. And as Dreyman begins to associate with known subversives and the investigatory noose tightens, Wiesler finds himself increasingly complicit in the machinations of the artists downstairs, so much so that he soon, if he’s not very, very careful, runs the risk of being the Stasi’s next target.

I can see the criticism that The Lives of Others can occasionally be a bit too pat. The distinctions between Wiesler and Dreyman are perhaps a bit overdrawn (Dreyman’s apartment is always suffused with a warm glow, and he and Sieland are invariably surrounded by friends, music, and the finer things in life; meanwhile, Wiesler scurries about the cold, gray machines upstairs, and basically lives like Eleanor Rigby — get a dog, Captain), and there are definitely a few cliche-ridden scenes along the way (for example, one involving the instantly transformative power of Beethoven — you’ll know what i mean.

Still, The Lives of Others is affecting in the details: Dreyman (“Lazlo”) and Sieland (“CMS”) are reduced to abstractions by the Stasi’s surveillance regime, with all the messy, conflicted, and emotion-ridden qualities that make them human drained away. (“They presumably have intercourse,” comments Wiesler dryly in his report after one tender moment.) Conversely, Wiesler’s attempts to break free of his own self-imposed leash and sound even the feeblest of barbaric yawps are moving in their own way, be it his sneaking out a dog-eared copy of Brecht from Dreyman’s shelf or renegotiating his interrogation strategy on an eight-year-old in his elevator.

Still, The Lives of Others is affecting in the details: Dreyman (“Lazlo”) and Sieland (“CMS”) are reduced to abstractions by the Stasi’s surveillance regime, with all the messy, conflicted, and emotion-ridden qualities that make them human drained away. (“They presumably have intercourse,” comments Wiesler dryly in his report after one tender moment.) Conversely, Wiesler’s attempts to break free of his own self-imposed leash and sound even the feeblest of barbaric yawps are moving in their own way, be it his sneaking out a dog-eared copy of Brecht from Dreyman’s shelf or renegotiating his interrogation strategy on an eight-year-old in his elevator.

The Lives of Others ends with a coda that at first seems too long but ultimately sounds just the right note: As Auden memorably put it, There is no such thing as the State, and no one exists alone; Hunger allows no choice to the citizen or the police; We must love one another or die. May I, composed like them of Eros and of dust, beleaguered by the same negation and despair, show an affirming flame.

Well, I’m not very happy about being on the other end of the review spectrum for this film, which was one I’d been really looking forward to. But, I must confess, I’m somewhat mystified by the

Well, I’m not very happy about being on the other end of the review spectrum for this film, which was one I’d been really looking forward to. But, I must confess, I’m somewhat mystified by the  So, here’s the setup: Once upon a time — 1944, to be exact — there was a young girl on the verge of adolescence named Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) who was forced to accompany her sickly, pregnant mother (Ariadna Gil) into the Spanish countryside, and to live with her wicked (Fascist) stepfather (Sergi Lopez of

So, here’s the setup: Once upon a time — 1944, to be exact — there was a young girl on the verge of adolescence named Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) who was forced to accompany her sickly, pregnant mother (Ariadna Gil) into the Spanish countryside, and to live with her wicked (Fascist) stepfather (Sergi Lopez of  But do they collide? Perhaps I missed some vital subtext, but I found Ofelia’s dreamworld adventures — other than the “Girl, you’ll be a Woman soon” flourishes, like the bloody book — to be generally remote both from her problems at home and from the Republican-Fascist feud, other than that all three narrative strands grow increasingly grisly and grotesque. And, while certain scenes definitely linger in the senses like eerie reminiscences of a fever dream, most notably the Wraith’s Table, they don’t really serve the larger story in any way I could fathom. (Also, why does Ofelia suddenly decide to go all Augustus Gloop in that scene anyway? Dream logic, I guess, but it seemed out of character.) Throw in a few second-act torture scenes that are more off-putting than they are resonant or even necessary, and Labyrinth starts to wear thin well before the end. In sum, Pan‘s a decent film that’s worth seeing if you’re in the mood for it, but it’s by no means the genre classic it’s being made out to be. Perhaps the subtitles gave it gravitas in some corners, but, to my mind, Pan’s Labyrinth gets a little lost in its own maze.

But do they collide? Perhaps I missed some vital subtext, but I found Ofelia’s dreamworld adventures — other than the “Girl, you’ll be a Woman soon” flourishes, like the bloody book — to be generally remote both from her problems at home and from the Republican-Fascist feud, other than that all three narrative strands grow increasingly grisly and grotesque. And, while certain scenes definitely linger in the senses like eerie reminiscences of a fever dream, most notably the Wraith’s Table, they don’t really serve the larger story in any way I could fathom. (Also, why does Ofelia suddenly decide to go all Augustus Gloop in that scene anyway? Dream logic, I guess, but it seemed out of character.) Throw in a few second-act torture scenes that are more off-putting than they are resonant or even necessary, and Labyrinth starts to wear thin well before the end. In sum, Pan‘s a decent film that’s worth seeing if you’re in the mood for it, but it’s by no means the genre classic it’s being made out to be. Perhaps the subtitles gave it gravitas in some corners, but, to my mind, Pan’s Labyrinth gets a little lost in its own maze.