“Hemmed in by term limits that will force him to leave office after the 2009 municipal election, Bloomberg seems to be searching for new worlds to conquer. With Eliot Spitzer just inaugurated as New York’s first Democratic governor in 12 years, there is only one elective job soon to be vacant for a politician with Bloomberg’s bent for executive leadership — and its home office is on Pennsylvania Avenue.” In Salon, Walter Shapiro wonders if Mayor Mike Bloomberg is considering an independent run in 2008. Well, I’d prefer Hizzoner to everyone in the Republican field, but don’t really imagine myself leaving the Dem fold to vote for him.

Category: NYC

A Most Rare Vision.

Joel Lobenthal of the NY Sun: “As Gamzatti, Gillian Murphy imprinted infallibly etched images of pride, love, and ruthless will. She has studied the role so thoroughly and respectfully that even when she brings her own time and culture to Gamzatti’s rarified reactions and body language, they don’t coarsen her performance, but rather add to its vitality. Ms. Murphy has refined her natural facility for turning, so that her multiple fouettes in the Pas d’Action coda were smooth as silk, and her pirouettes in her last act solo, followed by an echoing spiral into the upper body, were mesmerizing.” Or, says Jennifer Dunning of the NYT: “Once again Ms. Murphy made Gamzatti as pitiable a creature as she is evil, but this is a ballerina who needs a substantial work created for her.” Yes, it’s ABT’s summer season time at the Met, and once again Gill is rocking the house. I’ve caught her in Othello and The Dream (that’s her as Titania at right) thus far, and both times she was grand. If you’re in the NYC area and looking for an evening out, check the listings — you won’t be disappointed.

Joel Lobenthal of the NY Sun: “As Gamzatti, Gillian Murphy imprinted infallibly etched images of pride, love, and ruthless will. She has studied the role so thoroughly and respectfully that even when she brings her own time and culture to Gamzatti’s rarified reactions and body language, they don’t coarsen her performance, but rather add to its vitality. Ms. Murphy has refined her natural facility for turning, so that her multiple fouettes in the Pas d’Action coda were smooth as silk, and her pirouettes in her last act solo, followed by an echoing spiral into the upper body, were mesmerizing.” Or, says Jennifer Dunning of the NYT: “Once again Ms. Murphy made Gamzatti as pitiable a creature as she is evil, but this is a ballerina who needs a substantial work created for her.” Yes, it’s ABT’s summer season time at the Met, and once again Gill is rocking the house. I’ve caught her in Othello and The Dream (that’s her as Titania at right) thus far, and both times she was grand. If you’re in the NYC area and looking for an evening out, check the listings — you won’t be disappointed.

Rooms in New York.

“Sexual tension is at the heart of Hopper’s Room in New York, a scenario we peer at through an open window. Home from work, the man reads the sports page. Dressed to go out, the woman plays a single note on the piano, knowing it will annoy him. Their faces are almost as featureless as the blank sheet of music on the piano. Separated by the abstract expanse of the tall brown door, they are literally out of touch. But look a little closer at that fleshy pink armchair…Doesn’t that pink chair look unsettlingly like a huge hand, a jutting thumb and curled fingers, ready to clutch the unsuspecting man from behind and give him a shake? Is this the woman’s fantasy?“

Mount Holyoke English professor Christopher Benfey surveys “Edward Hopper’s secret world” for Slate, commenting at length on a painting whose iconography I’ve been shamelessly pilfering for years here, at the personal site, and elsewhere. Interesting…I always felt the picture captured a state of anomie and self-inflicted loneliness more than it did sexual tension — It’s a furtive through-the-window look at two people crammed into a tiny little room in New York basically ignoring each other. Or, more to the point, the man at left, caught up in the newspaper (news, not sports!) is so distracted by the world at large that he’s shut out his neglected lover at the piano: In his attention to distant events, he’s missing out on the beautiful things in his own life. But, hmm, that chair…

The GOP’s Finest.

“It was a running joke that some of the new faces were 25- to 32-year-old males asking, ‘First name, last name?'” A front-page story in today’s NYT discloses that the NYPD spied on possible RNC protesters for over a year before the 2004 convention, including several unlikely candidates — such as Billionaires for Bush — for anything other than lawful political protest. “‘The police have no authority to spy on lawful political activity, and this wide-ranging N.Y.P.D. program was wrong and illegal,’ Mr. Dunn [of the ACLU] said. ‘In the coming weeks, the city will be required to disclose to us many more details about its preconvention surveillance of groups and activists, and many will be shocked by the breadth of the Police Department’s political surveillance operation.’”

Ban Ki-Moon (and Spitzer) Rising.

Other important leadership shifts, these in and around New York: Having officially replaced Kofi Annan at the UN earlier this week, new general secretary Ban Ki-Moon cleans house, announces his own team and sets the Darfur crisis as a top priority. And, over in Albany, New York governor (and future presidential contender?) Eliot Spitzer delivers both his first Inaugural [text] and his first State of the State [PDF]: “In an hourlong address that was largely a repudiation of the policies of his predecessor, George E. Pataki, the new governor said he would seek to broadly overhaul the state’s ethics and lobbying rules. He said he would make prekindergarten available to all 4-year-olds by the end of his term, overhaul the public authorities that control most of the state’s debt and make New York more inviting to business by reducing the cost of workers’ compensation.“

Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues, Redux.

Hey all…I’m now back in New York City, tan, rested, and ready for whatever 2007 may bring. (I hope.)

Goldengrove Unleaving.

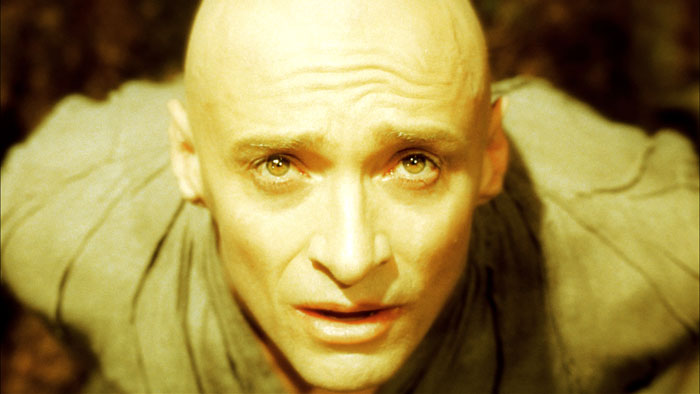

Admirably ambitious and running the emotional gamut from syrupy to sublime, Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain is a resolutely uncommercial big-think sci-fi piece that I expect will strongly divide audiences. (My guess is, you’ll either love the film or turn on it in the first half-hour.) I found it a bit broad at times, particularly in the early going, and I definitely had to make a conscious decision to run with it. That being said, I thought The Fountain ultimately pays considerable dividends as a stylish, imaginative, and melancholy celebration of the inexorable cycle of life, from birth to death ad infinitum. In its reach, The Fountain at times suggests 2001, and even if that reach probably exceeds its grasp by the end, it should still be applauded for so fearlessly tackling such heady themes, box office be damned. And if nothing else, The Fountain will not only make you contemplate the meaning of it all, but contains several haunting images, like scraps of a fever dream, that will resonate long after the movie’s over. All in all, not bad for ten bucks.

Like Requiem for a Dream and especially Pi, The Fountain is more about mood than plot, per se. Nevertheless, we begin in the sixteenth century, with a scruffy conquistador (Hugh Jackman, having a banner year) paying respects to what appears to be his beloved (Rachel Weisz) before embarking on a suicide mission against a Mayan temple. Before we’re fully acclimated to what’s going on, we’ve leapt to the twenty-sixth century (No, no Twiki), where that conquistador is now a bald, tattooed, Tai Chi practicing monk, traveling across the cosmos with an ailing tree and suffering visions from an age long hence. After a few bewildering minutes here, we find ourselves in our present, where neuroscientist Tom Creo (Jackman) is struggling against time to develop a cure for his wife Izzy (Weisz), before she succumbs to a brain tumor. As The Fountain progresses and we switch back and forth through these three timelines, a picture slowly coalesces of a man-out-of-time (no, not him either), determined beyond all bounds of hope or reason to defeat death and defend his one, true love from its thrall.

In all honesty, The Fountain suffers from some clunky moments in the early going, particularly when Weisz is forced to deliver exposition regarding Mayan beliefs about the Tree of Life, Xibalba (the Mayan underworld), and the Orion Nebula. And some, such as former Slate writer David Edelstein, couldn’t seem to get past the Clint Mansell score, which — as in Pi and Requiem — is hypnotic-bordering-on-intrusive. But, once you get past the somewhat unwieldy set-up, I found the movie’s themes considerably more sophisticated and less banal than most reviewers are giving it credit for. The romance here is pushed front-and-center, sure, but I found The Fountain moving less as a simple love-conquers-all tale than as an eloquent Zen meditation on mortality. (As one character puts it in the film, “Death is the road to awe.”) If matter is neither created nor destroyed, then, in a way, we are all immortal — the elements that make us up were around since the Big Bang and will continue to be around, reconstituted in other forms, long after we’re dead (“in the stars above, in the tall grass, and the ones we love,” to paraphrase a poet when he contemplated a similar plight to Jackman’s.) Indeed, in this fashion, each of us — made up of a combination of matter that, however briefly, has achieved sentience — is the universe trying to express itself. That is no small thing.

Moreover, in The Fountain (and akin to Jacob’s Ladder), Jackman’s character ultimately isn’t fighting to save his love as much as fighting his fear and despair over loss, not only of Weisz but of himself, his own ego: in short, his fear of death. As Weisz’s character says several times over, “I’m not afraid anymore.…Finish it.” Jackman’s Creo is afraid, so he won’t or can’t. “Without accepting the fact that everything changes, we cannot find perfect composure,” writes Shunryu Suzuki in Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. “But unfortunately, although it is true, it is difficult for us to accept it. Because we cannot accept the truth of transiency, we suffer.” To my mind, this suffering, and the overcoming of it, lies at the heart of Aronofsky’s The Fountain. I thought the richness of both its vision and its ideas helps it elide over a lot of the pacing and exposition problems in the early going. So, in sum, go see The Fountain: I’m not sure you’ll like it — it’s very possible you’ll love it — but I’m willing to bet, either way, that it’ll stick with you.

[One addendum/caveat/boast: As it happens, I saw The Fountain Monday night at a very private screening/cocktail affair. (How’d I get in? Long story…basically, Aronofsky and I have a mutual friend.) I’ve admitted earlier to being an inveterate celebrity hound, and in terms of celeb-spotting this was manna from Heaven. Of maybe 40-50 attendees, 10-15 were instantly recognizable folk: Not only Aronofsky, Jackman, Weisz, and Ellen Burstyn (also in the film), but a gaggle of other high-profile celebs: Bowie(!), Lou Reed, Mike Myers, Iman, Helena Christiansen, Ben Chaplin, Elizabeth Berkeley, etc. So, I’m almost positive I’d have liked and recommended The Fountain regardless, but I’m forced to admit (re: would like to brag) that I saw it under more-than-ideal circumstances. (Yes, I played it cool despite being famestruck, but I’d be lying if every so often in the first half-hour of the film I found myself thinking “Am I really sharing an armrest with Famke Janssen right now? How bizarre.” Not very Zen of me, I know, but sometimes I’m just a material guy.)]

Hail to Hizzoner?

First Vilsack, then McCain…Now Rudy Giuliani looks to be throwing his hat in the 2008 ring. But is the GOP base really of a New York state of mind? Somehow, I’d doubt it.

Going to the carnival.

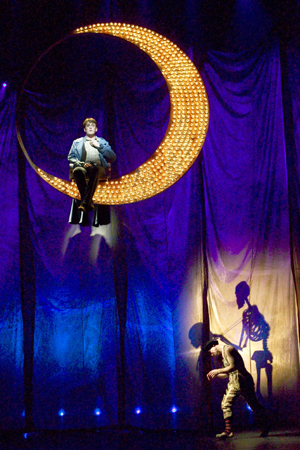

So, my sister, her boyfriend, and I went to check out The Times They Are A-Changin’, the new Twyla Tharp-choreographed reimagining of famous Bob Dylan songs, last Thursday (with, as a star-gazing aside, some heavy-hitters in attendance: Annie Leibowitz sat directly in front of me, and Tharp herself sat directly behind. Yes, I’m a celebrity hound.) And the verdict? Well, first let me say, that — some early dabbling in community-theater notwithstanding — I’m really not much of a musical guy. I tend to find the American Idol-ish histrionics of Broadway singing really distracting, and particularly when the song in question is something like “Masters of War.” Nor have I seen Moving Out, Mamma Mia!, Ring of Fire, Almost Heaven or any of the other “Broadway Karaoke” shows that currently seem to be the rage, so I can’t really compare it to any of the others — I was really more interested to see some intriguing interpretations of Dylan than I was to partake in a group sing-a-long (which, thankfully, Times is not.) With all that said, I found Times to be…kinda hit-or-miss. While some of the visions here do their source material justice in memorable fashion, others fall flat or just seem ill-conceived. And, while the circus acrobatics on display are amazingly well-performed and at times mesmerizing, too many numbers slip into the same dark carnival-of-the-absurd pattern. The cast works hard, but surely, when you get down to it, there is more to Dylan’s oeuvre than just aggro carny folk.

To its credit, Times samples songs from across Dylan’s career, from the hoary (“The Times They-Are A Changin’,” “Blowing in the Wind“) to the obscure (“Man Gave Names to All the Animals,” “Please, Mrs. Henry“), through the lean years (“I Believe in You,” “Dignity“) and up to the recent critical revival (“Not Dark Yet,” “Summer Days.”) Set in a traveling circus run by the vicious, heavy-handed Captain Ahrab (Thom Sesma) — a character from one of Dylan’s great American fables,”Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” not included — the play basically centers around a love triangle among Ahrab, his son Coyote (Michael Arden), and the lady Cleo (Lisa Brescia), one of the circus performers. Through their story — and the larger tale of a power struggle over the circus — are refracted these thirty or so Dylan tunes, strung togther in haphazard but decently compelling fashion.

I’d like to say there’s a formula for when a song works and when it doesn’t, but it doesn’t go over like that. One of the two best numbers, “Simple Twist of Fate” (the only cut from Blood on the Tracks here), is played basically straight. Alone in spotlight, Ahrab sings wistfully in the foreground (as seen at left) while the younger couple cavorts behind him, a haunting memory. “He woke up, the room was bare. He didn’t see her anywhere. He told himself he didn’t care, pushed the window open wide. Felt an emptiness inside, to which he just could not relate.” The bleak, melancholic staging matches the song perfectly, and Ahrab/Sesma channels both its poetry and its pain.

But, in the other most successful number, “Mr. Tambourine Man” (a song I can usually take or leave), Tharp & co. have taken a tune that’s ostensibly about a drug deal and just ran with it. Now, it’s a gripping, Bergmanesque dance of death, with one of the sadder clowns (Charlie Neshyba-Hodges) holding center stage as the ensemble circles around him in black, recalling the doomed pilgrims of The Seventh Seal. Obviously, Tharp isn’t the first to read “Tambourine Man” as a disquisition on mortality. (“I’m ready to go anywhere, I’m ready for to fade…into my own parade, cast your dancing spell my way, I promise to go under it.“) Nevertheless, the staging both feels innovative and cuts close to the bone of the song in surprising fashion.

There are other good moments scattered throughout the show, although few that hold their power over the course of an entire track: For example, a contortionist writhes horribly on a hospital bed during the “Dr. Filth” passage of “Desolation Row,” flashlights whirl and twirl (held by people brandishing them vaguely like tusken raiders) during “Knocking on Heaven’s Door“, the cast memorably get their drink on for “Please, Mrs. Henry,” and one clown reenacts Dylan’s “Subterranean” signage during the latter half of “Like a Rolling Stone.”

But, when a song’s off, it’s pretty off. The most obvious offenders are “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” “Blowing in the Wind,” and arguably “Lay, Lady, Lay,” all of which are performed in a deadly earnest Broadway patter that just stop the show dead. (This is particularly unfortunate in the case of the first one, since that’s how the show begins.) But, there are other problems. The bizarre welcome-to-the-carnival-of-beasties routine works well for “Desolation Row” (since, after all, “The circus is in town“) and maybe even for other rousing numbers such as “Like a Rolling Stone.” But, it’s overdone — in “Highway 61 Revisited,” “Everything is Broken,” “Gotta Serve Somebody,” “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” — to the point that the musical numbers become indistinguishable. (“Masters of War” also falls somewhat into this pattern — I liked it better than most, but was reminded more of ABT’s splendid recent revival of “The Green Table,” which captured the same sentiment better.)

And, sometimes, in my humble opinion, the attempted interpretation falls flat on its face. I thought turning “Not Dark Yet,” Dylan’s gloomy but resigned rumination on death around the corner, into a rage-against-the-dying-of-the-light completely misses the point of the song, which is that he’s given up and given in to the coming darkness. (“I’ve been down on the bottom of a world full of lies. I ain’t looking for nothing in anyone’s eyes.“)

Most egregious in this regard is what’s been done to “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.” Perhaps because it remains such a personal song — a song about two people rather than a generation — I’d say it’s aged much better than almost all of the other hugely popular early-Dylan standards (“Blowing in the Wind,” “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.”) In fact, I might go so far as to say that “Don’t Think Twice” may just be the quintessential Dylan break-up song in a career full of them (although now that I write that…Blonde on Blonde, Blood on the Tracks…ok, never mind. That’s too bold a statement.) At any rate, here, all the complexity of competing emotions that drives the track — “I ain’t sayin’ you treated me unkind, you could have done better but I don’t mind, you just kinda wasted my precious time” — is wasted, as it’s become, inexplicably, a number sung by a woman to her overly eager dog. (Although I will concede that the canine in question — I believe it was Jason McDole — was convincingly and creepily Berkeley-like.)

In sum, A Times They Are A-Changin’ is at times engaging, and may be worth catching if you have a hankering for the carnivalesque, if you’re a Dylan completist, or if you have a higher tolerance for showtune renditions than I do. But, as an exploration of Dylanalia, I found the show too narrowly circumscribed within its three-ring circus, and ultimately unsatisfying. (Then again, in the play’s defense, I didn’t think much of Masked and Anonymous either, so perhaps I’m just ornery about such things.)

Terry le Heros.

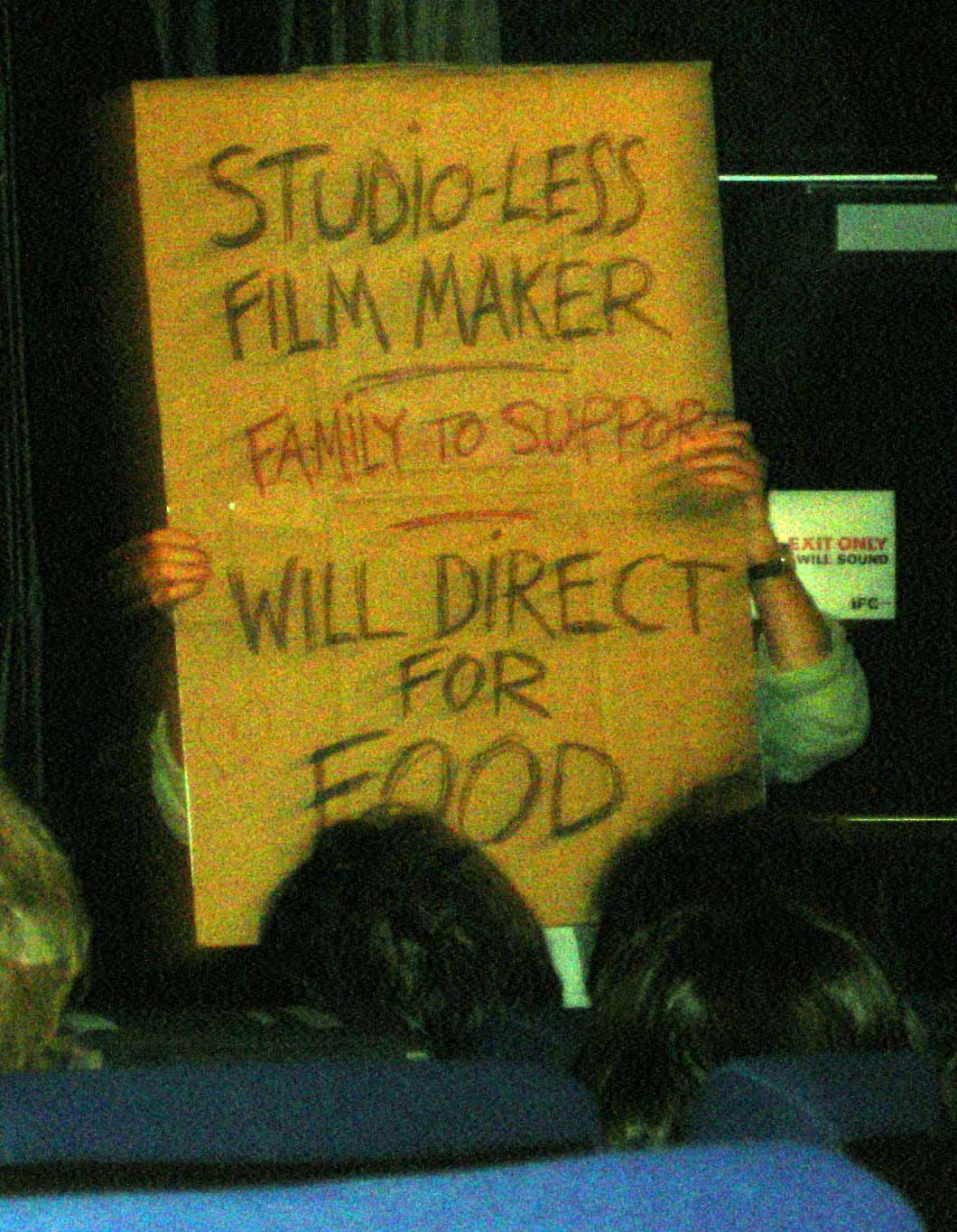

As longtime readers might know (or might’ve adduced from some of the site banners above), I’ve always been a big Terry Gilliam fan, and will pony up for films considerably worse than The Brothers Grimm to repay the man for making Time Bandits, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and one my all-time favorite movies, Brazil. (In fact, “Ghost in the Machine” is the name of this site partly for the Brazil reference.) So it was a real treat yesterday when I and a friend from high school got to see Terry Gilliam live in the flesh last night at the IFC Center on 4th St. After making the rounds in front of The Daily Show yesterday afternoon, Gilliam showed up as part of IFC’s Movie Night series, in which a director of some repute screens one of his favorite films. (In fact, he showed up with the sign he’d been lugging around outside all day: “STUDIOLESS DIRECTOR — FAMILY TO SUPPORT — WILL DIRECT FOR FOOD”) Apparently, Gilliam had wanted to show One-Eyed Jacks, the 1961 western directed by Marlon Brando, but the Brando estate wouldn’t deliver a print or somesuch.

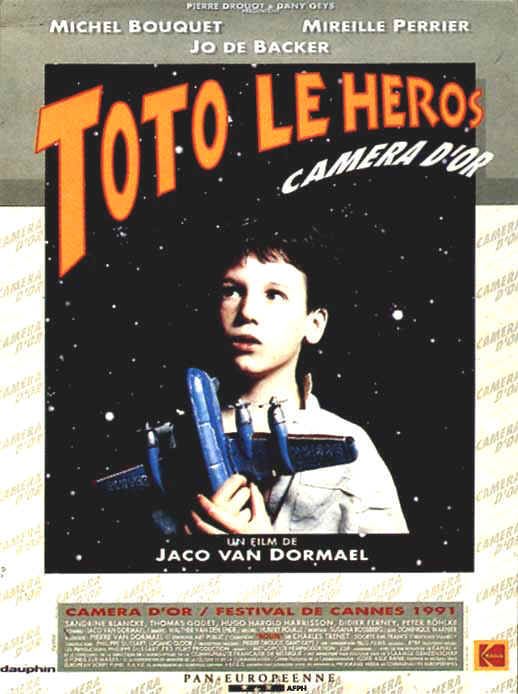

So, the film we got instead was Jaco von Dormael’s Toto le Heros (Toto the Hero), a bizarre Belgian concoction of 1991 that’s part Prince and the Pauper, part Singing Detective, part Citizen Kane and very Gilliamesque. A movie that’s hard-to-explain but that’s definitely worth renting, Toto follows the story of one Thomas van Haserbroeck (Don’t call him van Chickensoup), an imaginative young boy unsettlingly in love with his sister, a lonely man contemplating an affair with a mystery woman, and a deeply depressed senior citizen looking to exact revenge for a life-long grievance. Y’see, Thomas (or Toto, as he’s called in his dream life, where he’s a film noir gumshoe) insists he remembers being switched with another baby — his wealthy next-door neighbor, Albert Kant — during a fire at the hospital, and therein, in his mind, lies the source of most of his troubles. As the story switches back and forth in time, Toto and Albert’s lives keep butting against each other in strange doppelganger fashion, while old-Thomas enacts a plan to reclaim his stolen life…

After the movie, Gilliam returned to the front for a wide-ranging Q&A session, which involved questions both probing (“Did you borrow from Toto in 12 Monkeys?” [No, don’t think so.]) and peculiar (“Where’d you buy your shoes? Where’s the worst place you ever spent the night?” [Birkenstocks, some backwater hut in India]) Along the way, Gilliam told tales of first meeting the Python guys, photographing Frank Zappa in 1967, choosing his various directors of photography, and, the battle of Brazil notwithstanding, generally enjoying the constraints of studio heads and limited budgets. (They focus him.) Speaking of which, he also said Good Omens still seems to be moving forward, and Quixote may still happen someday. (He also mentioned The Defective Detective briefly, but it seemed in the past tense.) And these days he’s digging the new Dylan album, as well The Arcade Fire’s Funeral and The Flaming Lips’ At War with the Mystics.

At one point, he also said he was considering suing Bush, Cheney, et al for making an unauthorized remake of Brazil. With that in mind, I asked him whether his views on Brazil had changed at all now that we’re kinda living it. (I mean, what with Cheney playing Mr. Helpmann, Canadian citizens getting Buttled, and the Dubya team now fully sanctioning Jack Lints, what’s a good Sam Lowry to do, other than await his turn in the chair or on the waterboard?) He noted that, obviously, Brazil-type stuff was going on around the world at the time (in the Soviet bloc, Argentina, etc.) but that he watched the film the other day (to check out the new Criterion HD-DVD version) and was amazed at both how prescient and topical it was.

Throughout, Gilliam was amazingly friendly and personable, and came across a remarkably humble and down-to-earth guy. He kept taking questions well after the IFC-suit tried to close down the affair, and hung around the nearby cafe afterwards to sign various items. I ended up being the second guy in line, and got him to sign the Brazil still above (one of five I have framed in my hallway.) When he asked me my name for the signature, he lit up, “Kevin! Time Bandits Kevin!” I told him I was right around that age when I first saw Time Bandits, and he’s definitely got a lot to answer for.