The Cannes winner of 2007 (over No Country for Old Men, which I still preferred), Cristian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days, a fearless look at a very dark day in the life of two Romanian women, is a tremendously harrowing exercise in Hitchcockian suspense, and a grim, unrelenting journey into the moral compromises and bureaucratic decay that characterized life in Nicolae Ceausescu’s Romania. I have some issues with Mungiu’s film, which I’ll get to in a bit, but no one can deny that it’s a powerful and expertly-made movie, one that tortures with silences and devastates with quiet restraint. But it’s also, I have to admit, a film I admired more than truly enjoyed. That’s its intent, of course: I can’t think of any other movie I’ve seen lately that had me squirming with as much psychic discomfort. (Remember the visceral suspense of the hotel scene in No Country, when Chigurh passes by Llewelyn’s door and removes the hallway lightbulb? Now imagine having that feeling for over an hour.) Still, while I can’t deny 4 Month‘s emotional hold, I think I ultimately prefer The Lives of Others — a film that offsets its tragic tale with moments of grace, humor, and even redemption — when it comes to recent fables of the Eastern Bloc.

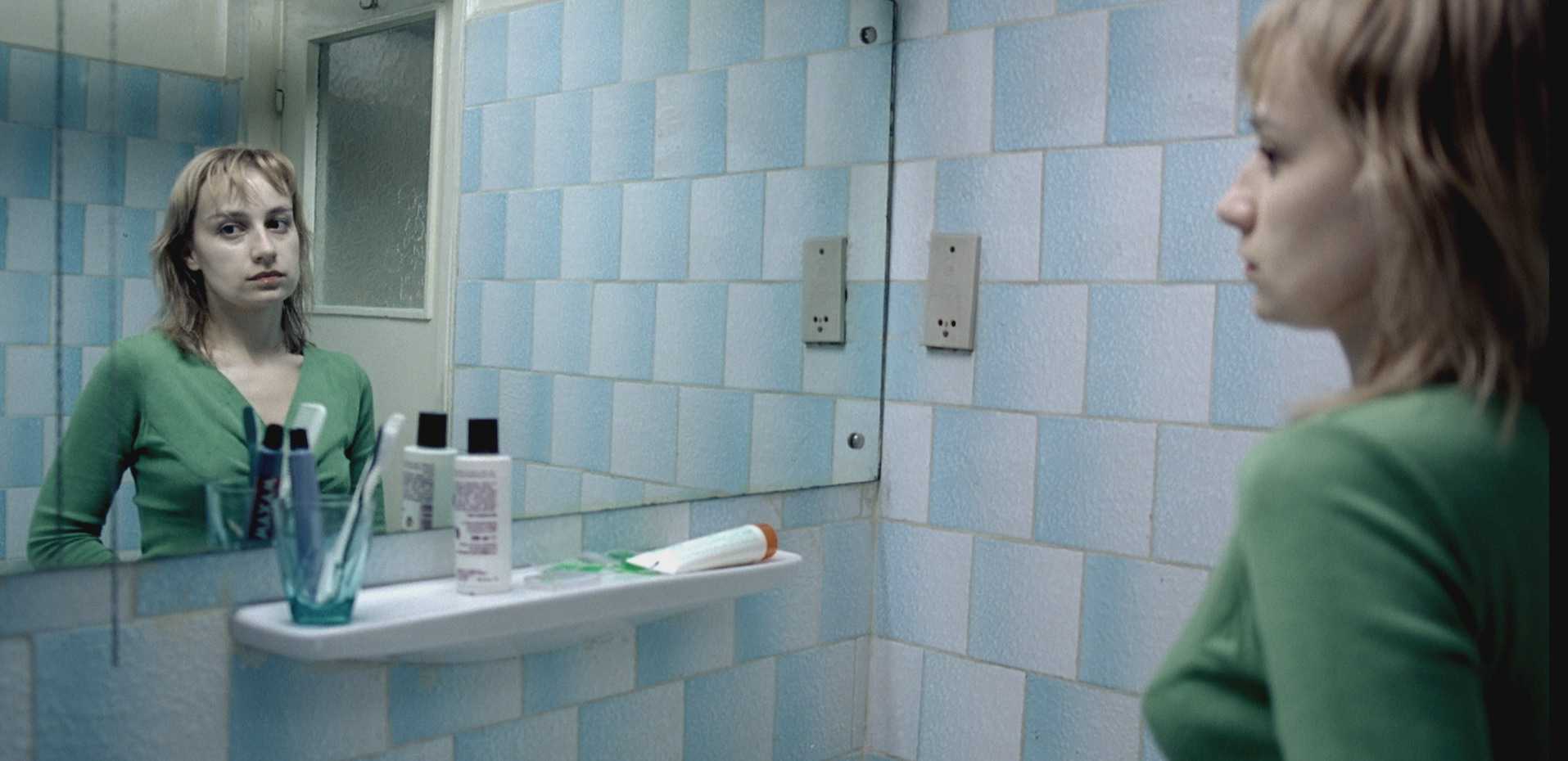

4 Months establishes its naturalistic, real-time feel from its opening moments, as we watch a young Romanian student named Gabita (Laura Vasiliu) fiddle with her belongings and seemingly make preparations for an important trip. As she frets, her roommate, Otilia (Anamaria Marinca, Oscar-worthy) wanders down the hall of their dormitory, navigating the nooks and crannies of a casual black market economy with a bored, practiced ease. (She picks up cigarettes for bribing officials, looks over the recent array of smuggled-in beauty products, and procures some Tic Tacs from a friendly dealer-neighbor.) But Otilia too gives the sense that something major is afoot, something we gradually glean the outlines of as the day goes along. Leaving Gabita behind, Otilia ventures out to lock down a nearby hotel room (something Gabita was previously meant to do, but apparently didn’t), borrows some money from her boyfriend (Alexandru Potoceanu), and eventually goes — on behalf of Gabita — to meet a Mr. Bebe (Vlad Ivanov, memorably sinister), a man we eventually come to learn is a back-alley abortionist.

Then, things get worse. For not only is abortion a criminal offense under the Ceausescu regime, one that carries a penalty of prison or even death, but the helpless Gabita (the pregnant one) turns out to be flaky and careless to the extreme, and basically an abuser of Otilia’s competence and compassion. Worst of all, the seemingly innocuous Mr. Bebe — despite dripping with doctorly condescension toward the “young ladies” — turns out to be the type of monster that can readily flourish in the interstices of totalitarianism, reveling in the power he manages to hold over the desperate Gabita and Otilia. And, even beyond the ruthless Bebe — who, trust me, is more than loathsome enough — there awaits the very real risk of medical complications, and the danger of discovery by the authorities…

Sustained by long, masterful, and unbroken shots, 4 Months manages to ratchet up the tension well beyond comfortable levels, making even scenes of a casual dinner party at Otilia’s boyfriend’s house palpable with dread. Like the two women at the center of the story — and, like many people living through totalitarianism, I’d suspect — we’re constantly on pins and needles, waiting for the other shoe to drop. (But don’t get me wrong — some really horrifying shoes drop in this film.) As a remorseless and nerve-wracking Eastern bloc thriller, 4 Months has few parallels I can think of. So why do I harbor reservations about the film? Well, four years, 0 months, and 3 days ago, I wrote of the considerably overpraised 21 Grams that it “just ambles around in its terminally depressed jag for so long that it loses any sense of perspective, and instead becomes just a vehicle for indulging the arthouse fallacy that misery is a substitute for character.” Now, 4 Months is a much, much better film than 21 Grams, but — however tense and suffused with menace — the same problem persists.

Coming out of 4 Months, I was reminded of an interview I read with David Simon about the importance of humor in The Wire, which however bleak is also by all accounts a gut-bustingly funny show. (I know, I won’t shut up about The Wire, but bear with me here.) This article makes the same point: “Though people don’t talk much about the humor in ‘The Wire,’ it’s there. You drop somebody into an alien environment — a closed society like the homicide cops or the drug culture–and the key to working your way into that culture is to understand the jokes, which David does. It’s crucial, because, if it weren’t there, the work would be too depressing. It’s crushing subject matter, but not necessarily to the cops–they’re making jokes while they’re looking at dead bodies–and not to the people shooting dope, even. They’re not necessarily walking around saying, ‘Woe is me.’ There’s a grim humor that springs out of that life.” Picking up along the same lines, Jacob Weisberg wrote: “While The Wire feels startlingly lifelike, it is not in fact a naturalistic depiction of ghetto life. That kind of realism better describes an earlier miniseries of Simon’s, The Corner…The Corner seems to have been a crucial life study for The Wire, a program that attains the dimensions of tragedy without being depressing. The Wire does this by painting with brighter colors on a wider canvas and by leavening its pain with humor…What ultimately makes The Wire uplifting amid the heartbreak it conveys is its embodiment of a spirit that Barack Obama calls ‘the audacity of hope.’” (You see how I snuck in an Obama reference with a Wire reference? See, I’m always on message.)

Seriously, though, it’s that critique which gets to the heart of my hesitation about fully embracing 4 Months. I don’t fault its unflinching refusal to sugar-coat what amounts to a horrible tale in a sad time and place, and it probably speaks worse of me than of Mungiu’s film to even hold such a thing against it. Many stories — maybe even most of them — don’t have happy endings or a laugh track. And, after all, we watch Otilia and Gabita persevere through an extraordinary amount of suffering, so why should they have to crack a joke just to let us off the hook, and make us feel better about their obvious misery? Still, if you can look past the razor-sharp tension that drives 4 Months, it is a relentlessly downbeat — and even one-note — affair. 4 Months is an impressive and powerful movie in any event, but I think I’d hold the film in higher esteem if it — like The Lives of Others — occasionally broke the gloom and allowed its long-suffering characters an uncertain smile, even while staring into the abyss.