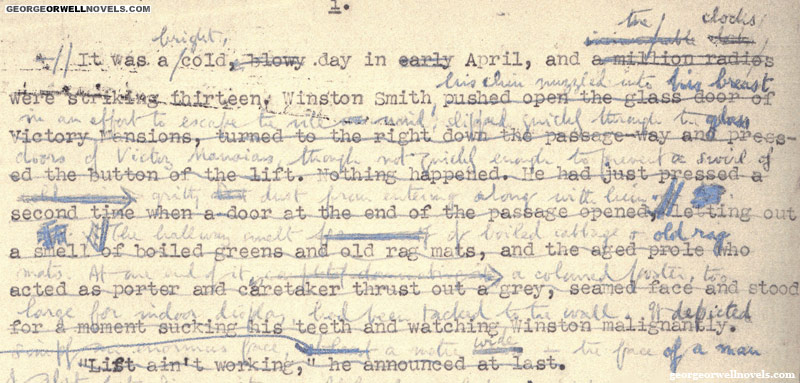

“The sketch on the right side of this page of notes, with its annotations (“body dark grey”; “all appendages not in use customarily folded down to body”; “leathery or rubbery”) represents Lovecraft working out the specifics of an Elder Thing’s anatomy. As Lovecraft’s narrator was a scientist, the description of the Things in the novella is dense and layered; here we can see the beginnings of that detail.”

“The sketch on the right side of this page of notes, with its annotations (“body dark grey”; “all appendages not in use customarily folded down to body”; “leathery or rubbery”) represents Lovecraft working out the specifics of an Elder Thing’s anatomy. As Lovecraft’s narrator was a scientist, the description of the Things in the novella is dense and layered; here we can see the beginnings of that detail.”

Speaking of taking notes: In her house at S’late, Rebecca Onion points the way to H.P. Lovecraft’s handwritten notes for At the Mountains of Madness. “The writer, who had fallen on hard times, used a deconstructed envelope in an attempt to save paper.”

Also, I forget if I’ve blogged this before, but I found this interesting read while looking to briefly shoehorn Lovecraft into the dissertation: Lovecraft’s final years as a New Dealer:

“As for the Republicans—how can one regard seriously a frightened, greedy, nostalgic huddle of tradesmen and lucky idlers who shut their eyes to history and science, steel their emotions against decent human sympathy, cling to sordid and provincial ideals exalting sheer acquisitiveness and condoning artificial hardship for the non-materially-shrewd, dwell smugly and sentimentally in a distorted dream-cosmos of outmoded phrases and principles and attitudes based on the bygone agricultural-handicraft world, and revel in (consciously or unconsciously) mendacious assumptions (such as the notion that real liberty is synonymous with the single detail of unrestricted economic license or that a rational planning of resource-distribution would contravene some vague and mystical ‘American heritage’…) utterly contrary to fact and without the slightest foundation in human experience? Intellectually, the Republican idea deserves the tolerance and respect one gives to the dead.”