While there’s no one hard and fast rule to a good artist biopic (and, indeed, last week’s Capote belies to some extent what I’m about to say), it should capture what’s innovative and idiosyncratic about its subject, and help to explain why we should care about their artistry. And, while James Mangold’s reasonably entertaining Walk the Line has its moments, and Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon are both excellent, I ultimately found this movie somewhat frustrating. For, except for occasional flashes, the movie, I think, misses the chance to do Johnny Cash justice — you never really get a sense of what was so unique and extraordinary about him. And, even considered solely as the romance of the Man in Black and his long-suffering muse, June Carter (of the fabled Carter Family,) Walk the Line stumbles ever so slightly. If you came into this film knowing nothing about Johnny Cash or June Carter Cash, I’m not sure this movie makes their case. Too often, it follows a standard Behind the Music “rise, drug-addled-fall, and rise again” structure, which makes it feel like it could be about, well, anybody.

While there’s no one hard and fast rule to a good artist biopic (and, indeed, last week’s Capote belies to some extent what I’m about to say), it should capture what’s innovative and idiosyncratic about its subject, and help to explain why we should care about their artistry. And, while James Mangold’s reasonably entertaining Walk the Line has its moments, and Joaquin Phoenix and Reese Witherspoon are both excellent, I ultimately found this movie somewhat frustrating. For, except for occasional flashes, the movie, I think, misses the chance to do Johnny Cash justice — you never really get a sense of what was so unique and extraordinary about him. And, even considered solely as the romance of the Man in Black and his long-suffering muse, June Carter (of the fabled Carter Family,) Walk the Line stumbles ever so slightly. If you came into this film knowing nothing about Johnny Cash or June Carter Cash, I’m not sure this movie makes their case. Too often, it follows a standard Behind the Music “rise, drug-addled-fall, and rise again” structure, which makes it feel like it could be about, well, anybody.

To its credit, the film starts off well — We begin on a chilly day outside Folsom Prison in 1968, as a guard nervously listens to an ominous throb emanating from and through the high, grey walls. Slowly, it resolves into a readily identifiable Cash backbeat, and we go inside to find the Man in Black’s band waiting for him to take the jailhouse stage. But Cash is lost in reverie, struck by the sight of a buzzsaw blade in the prison shop room. For a soon-to-be-obvious reason, it takes him back to his boyhood days picking cotton in rural Arkansas, where the sounds of trains going someplace else are always in the distance, and the only respite from the sweltering heat is the voice of young June Carter on the radio. Ok, so far, so good…Mangold has shown that he’s not afraid to keep everything a little impressionistic, to color his palette with iconographic Cash-isms and help the man’s music breathe through the picture.

Unfortunately, though, most of the film thereafter feels depressingly literal. After apprising us of a childhood tragedy, the film takes us through Cash’s early days in the Air Force, his increasingly loveless first marriage to Vivian Liberto (Ginnifer Goodwin, looking like Audrey from Twin Peaks and feeling like a stock biopic trope), his rise to fame, his subsequent addiction to Go Pills, and his ultimate redemption thanks to a good-hearted woman, always there to help out a good-timin’ man in his hour(s) of need. This is all capably handled, I guess, but too often it feels rote, in an Insert-Rock-Star-Here kinda way. Worse, aside from one discerning monologue by rock-n-roll impresario Sam Phillips (Dallas Roberts) at Cash’s first audition, the film never really gets to the bottom of the singer’s appeal. We see Cash on his all-star Sun Records tours — and thus get impersonations of Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, and Carl Phillips, among others — but the film never explains what was unique about Cash among Phillips’ impressive stable of talent. (No Dylan here later on, though…but Cash’s close friendship with Bob is explicitly referenced several times, including a timely cover of “It Ain’t Me, Babe” and a lively use of “Highway 61“‘s police whistle intro.)

Unfortunately, though, most of the film thereafter feels depressingly literal. After apprising us of a childhood tragedy, the film takes us through Cash’s early days in the Air Force, his increasingly loveless first marriage to Vivian Liberto (Ginnifer Goodwin, looking like Audrey from Twin Peaks and feeling like a stock biopic trope), his rise to fame, his subsequent addiction to Go Pills, and his ultimate redemption thanks to a good-hearted woman, always there to help out a good-timin’ man in his hour(s) of need. This is all capably handled, I guess, but too often it feels rote, in an Insert-Rock-Star-Here kinda way. Worse, aside from one discerning monologue by rock-n-roll impresario Sam Phillips (Dallas Roberts) at Cash’s first audition, the film never really gets to the bottom of the singer’s appeal. We see Cash on his all-star Sun Records tours — and thus get impersonations of Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, and Carl Phillips, among others — but the film never explains what was unique about Cash among Phillips’ impressive stable of talent. (No Dylan here later on, though…but Cash’s close friendship with Bob is explicitly referenced several times, including a timely cover of “It Ain’t Me, Babe” and a lively use of “Highway 61“‘s police whistle intro.)

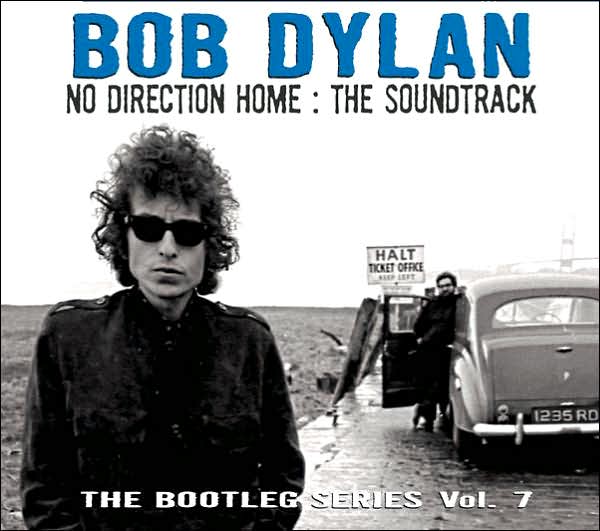

In fact, allow me to digress — one of the many fascinating aspects of the Dylan-Cash camaraderie (also briefly featured in one of the most memorable moments of the recent No Direction Home) is that, aside from a shared affinity for murder ballads and mind-altering substances, they were a study in contrasts, at least in the Sixties. Often, the young Dylan seems impetuous and invincible. Keenly aware of injustice, he nevertheless remains unfazed. He’s unrepentant in his anger — To paraphrase Herbert Croly‘s colorful description of Theodore Roosevelt, the early Dylan wields righteousness like a hammer, throwing the sins, taunts, and ridicule of this world right back from whence they came. Or, at many of his best moments, he turns his back on it all. Instead, he illuminates our experience by imagining the world anew, conjuring a landscape (what Greil Marcus has called the “invisible republic”) that renders both grievous sins and exalted sacraments to be often socially conditional, if not absurd and irrelevant.

In fact, allow me to digress — one of the many fascinating aspects of the Dylan-Cash camaraderie (also briefly featured in one of the most memorable moments of the recent No Direction Home) is that, aside from a shared affinity for murder ballads and mind-altering substances, they were a study in contrasts, at least in the Sixties. Often, the young Dylan seems impetuous and invincible. Keenly aware of injustice, he nevertheless remains unfazed. He’s unrepentant in his anger — To paraphrase Herbert Croly‘s colorful description of Theodore Roosevelt, the early Dylan wields righteousness like a hammer, throwing the sins, taunts, and ridicule of this world right back from whence they came. Or, at many of his best moments, he turns his back on it all. Instead, he illuminates our experience by imagining the world anew, conjuring a landscape (what Greil Marcus has called the “invisible republic”) that renders both grievous sins and exalted sacraments to be often socially conditional, if not absurd and irrelevant.

But Cash — Cash can’t escape his critics, because his worst critic is himself. Nor can he either simply condemn or intricately reimagine Evil, because he has been Evil’s instrument. He’s a man of our world — In fact, he’s the Last Man, the Fallen Man. (“But just so we’re reminded of the ones who are held back, Up front there ought ‘a be a Man In Black.”) Forget righteousness: Cash’s characters are just as cognizant of injustice as Dylan’s, but they also know they’ve done wrongs that can’t and never will be forgiven. They’ve been living desperate for so long they’ve become resigned to it. They walk the line, because they know what it’s like to stray far off the path, and they’ve paid the price in spades. And their adherence to their creed — be it a woman, the Savior, or something else, depending on the song — is all the more heartfelt and admirable because it has been tested, and even broken. In short, Cash has suffered grave consequences, and persevered in spite of them. He’s been through the Ring of Fire and out the other side, and his gravelly-delivered tales of guilt and penitence have set the stage for any number of later artists, including Tom Waits, Nick Cave, Leonard Cohen, and, by no coincidence at all, the older Bob Dylan.

But Cash — Cash can’t escape his critics, because his worst critic is himself. Nor can he either simply condemn or intricately reimagine Evil, because he has been Evil’s instrument. He’s a man of our world — In fact, he’s the Last Man, the Fallen Man. (“But just so we’re reminded of the ones who are held back, Up front there ought ‘a be a Man In Black.”) Forget righteousness: Cash’s characters are just as cognizant of injustice as Dylan’s, but they also know they’ve done wrongs that can’t and never will be forgiven. They’ve been living desperate for so long they’ve become resigned to it. They walk the line, because they know what it’s like to stray far off the path, and they’ve paid the price in spades. And their adherence to their creed — be it a woman, the Savior, or something else, depending on the song — is all the more heartfelt and admirable because it has been tested, and even broken. In short, Cash has suffered grave consequences, and persevered in spite of them. He’s been through the Ring of Fire and out the other side, and his gravelly-delivered tales of guilt and penitence have set the stage for any number of later artists, including Tom Waits, Nick Cave, Leonard Cohen, and, by no coincidence at all, the older Bob Dylan.

Well, that’s my take on Cash, and there are many others (For example, Ed Champion had a nice read on him last week contrasting Cash with Franz Ferdinand.) But, back to the movie — I barely got any sense of a Cash critique at all in Walk the Line. At best, it assumes you already have an opinion and appreciation of the man coming in, which may be true but still seems like lazy writing. (Or, alternatively, I guess you could say that it attempts to explode the Cash myth — “He wasn’t really a jailbird!” — but that gets us back into staid Behind the Music territory again.) That being said, the fault with the film is not Joaquin Phoenix’s by any means. Admittedly, his singing voice is off — although, whether it be to his getting better or my brain sorting out the cognitive dissonance — he improves as the film goes along. But, otherwise, Phoenix goes for it, and despite often seeming physically and vocally far afield from Cash, he delivers a powerful performance from the inside-out. As Dave Edelstein noted, it’s hard to watch him wrestle with drug abuse and the memory of his dead brother here and not think of River Phoenix. (If anything, I was reminded of Anthony Hopkins in Oliver Stone’s Nixon, which is another brilliant performance, although arguably one that doesn’t suggest Tricky Dick to anyone who remembers him.)

Well, that’s my take on Cash, and there are many others (For example, Ed Champion had a nice read on him last week contrasting Cash with Franz Ferdinand.) But, back to the movie — I barely got any sense of a Cash critique at all in Walk the Line. At best, it assumes you already have an opinion and appreciation of the man coming in, which may be true but still seems like lazy writing. (Or, alternatively, I guess you could say that it attempts to explode the Cash myth — “He wasn’t really a jailbird!” — but that gets us back into staid Behind the Music territory again.) That being said, the fault with the film is not Joaquin Phoenix’s by any means. Admittedly, his singing voice is off — although, whether it be to his getting better or my brain sorting out the cognitive dissonance — he improves as the film goes along. But, otherwise, Phoenix goes for it, and despite often seeming physically and vocally far afield from Cash, he delivers a powerful performance from the inside-out. As Dave Edelstein noted, it’s hard to watch him wrestle with drug abuse and the memory of his dead brother here and not think of River Phoenix. (If anything, I was reminded of Anthony Hopkins in Oliver Stone’s Nixon, which is another brilliant performance, although arguably one that doesn’t suggest Tricky Dick to anyone who remembers him.)

Reese Witherspoon is also superb (indeed, award-worthy) as June Carter, who, as in life, I suppose, was both a vivacious stage presence and a model of forbearance. (It’s also great to hear a genuine, unaffected southern accent onscreen. Too often, they sound actorly and are off by hundreds of miles — I’m looking at you, Cold Mountain.) But, the romance at the heart of the film is missing that certain je-ne-sais-quoi. From what little I know about it, Johnny and June Carter Cash are one of those love stories for the ages. She was his angel, his ray of light in the dark (images which the film does try to bring to life.) But, here, and I’m not quite sure exactly who’s at fault, Johnny Cash just comes off as a disciple of the mega-creepy Anakin Skywalker school of courting — i.e., act like a stalker for long enough and eventually she’ll come ’round. Again, I don’t really blame the actors. They do what they can with what they’ve got (although perhaps memories of Phoenix’s turn as Gladiator‘s Commodus are partially at fault.) But, to my mind, if the movie tried harder to sell us on Cash’s unique artistry, perhaps we’d have a better sense of what June, daughter of an estimable clan of folkies, saw in him. As it is, he just seems like an extremely lucky, albeit talented, amphetamine junkie.

Reese Witherspoon is also superb (indeed, award-worthy) as June Carter, who, as in life, I suppose, was both a vivacious stage presence and a model of forbearance. (It’s also great to hear a genuine, unaffected southern accent onscreen. Too often, they sound actorly and are off by hundreds of miles — I’m looking at you, Cold Mountain.) But, the romance at the heart of the film is missing that certain je-ne-sais-quoi. From what little I know about it, Johnny and June Carter Cash are one of those love stories for the ages. She was his angel, his ray of light in the dark (images which the film does try to bring to life.) But, here, and I’m not quite sure exactly who’s at fault, Johnny Cash just comes off as a disciple of the mega-creepy Anakin Skywalker school of courting — i.e., act like a stalker for long enough and eventually she’ll come ’round. Again, I don’t really blame the actors. They do what they can with what they’ve got (although perhaps memories of Phoenix’s turn as Gladiator‘s Commodus are partially at fault.) But, to my mind, if the movie tried harder to sell us on Cash’s unique artistry, perhaps we’d have a better sense of what June, daughter of an estimable clan of folkies, saw in him. As it is, he just seems like an extremely lucky, albeit talented, amphetamine junkie.

And, to close an overextended review, that’s the basic problem with Walk the Line. The parts are all here, but, aside from the occasional flicker of life, the soul of Cash is mostly absent. Perhaps it’d be impossible to do right by him, to capture all the mystique of his music and his persona on celluloid. But, that doesn’t make this film any less frustrating. Try as Walk the Line might, the elusive and unforgettable Johnny Cash remains a ghost rider in the sky.