When is the remake of a movie classic actually a good idea? When the brothers Coen are at the helm. (Let’s just say The Ladykillers is the exception that proves the rule.) Both laugh-out-loud funny and tinged with melancholy for the disappearing West, the brothers’ impressive adaptation of True Grit feels like the unearthing of a forgotten piece of Americana, and it makes the 1968 Charles Portis serial from which both movies are based feel as quintessential an American coming-of-age story as To Kill a Mockingbird. Whether you love, hate, are indifferent or just oblivious to the John Wayne-Kim Darby-Glen Campbell version of 1969, this is one remake that’s worth your time.

I should say that I haven’t seen the original movie, which I remember as more family-friendly and Old Yeller-ish than this version, since I was a kid — younger even than Mattie Ross, True Grit‘s 14-year-old protagonist. I do remember liking the film, and I’m pretty sure it was my first-ever exposure to John Wayne, Movie Star. (At the time, I had no idea that the Duke as Rooster Cogburn was basically stunt-casting.) Nor have I read the source material, so I really can’t tell you how faithful the Coens are being to Portis’ novel either (or for that matter, Night of the Hunter, which the brothers — and Carter Burwell’s score — apparently reference early and often in this film.)

Word is the brothers have gone the extra mile to keep Portis’ prose front and center in this version, and that may well be true. Still, there are more than enough wry conversations, colorful eccentrics, and sudden spurts of violence here to suggest that, at the very least, Portis is a spirtual ancestor and kindred spirit to the Coenverse. (Maybe it’s just a coincidence that Mattie seems to channel The Big Lebowski‘s Walter in one of her first scenes, when she complains about the high cost of burying her father, but the wandering frontier dentist in a bear suit had to have been a Coen creation, yes?)

In any case, in this telling of the tale, Mattie Ross (newcomer Hailee Steinfeld, a find) is considerably younger than Kim Darby was in 1969, and she, not Rooster, is the heart of the film. As True Grit begins, her father Frank lies dead in the Arkansas snow, shot down by a no-good lout named Tom Chaney (Josh Brolin), who’s since gone on the lam in Cherokee territory. And since no one else seems to care, it falls to the young, headstrong, and remarkably worldly-wise Ms. Ross to make arrangements. That means paying for the funeral, putting her father’s things in order, and finding somebody to hunt down Chaney and bring him to justice. (“The wicked flee when none pursueth,” admonishes the title card by way of Proverbs 28:1. If Mattie gets her way, that won’t be a problem.)

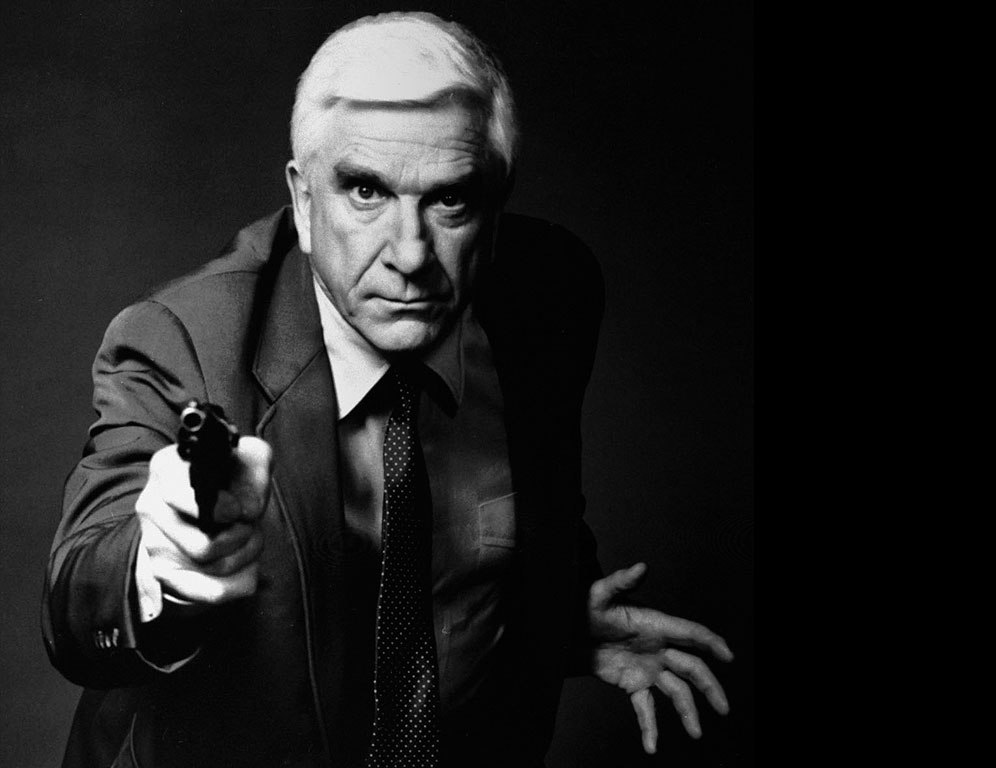

And so, to track down her father’s killer, Mattie enlists the services of the meanest (and drunkest) US Marshall she can find — an ornery, one-eyed old cuss named Reuben “Rooster” Cogburn (Jeff Bridges, leaving the Lebowski-ish affectations back at Encom.) Also along for the ride, on account of an earlier crime by Chaney down in Texas, is Mr. LaBoeuf (Matt Damon), a well-meaning but slow-witted Ranger who’s at turns goofus and gallant. So, a little girl, an old drunk, and a nincompoop: It’s not exactly the most promising posse in the world, particularly once word comes that Chaney is hanging with Lucky Ned Pepper’s gang (here played by Barry Pepper — a descendant?) Still, the codger may still have a few tricks up his sleeve yet, and, as she shows time and again, Mattie is nothing if not a force of will.

If you’ve seen the original film, you know the hunt for Chaney is mostly a chance for this posse to get to know each other over a series of conversations and episodic vignettes. And that’s how it plays out here, too, except both LaBoeuf and Cogburn are less heroic and more conflicted buffoons this time around, and Mattie has to figure out over the course of her travels if these two are — literally and figuratively — straight shooters. It’s a tough call: LaBoeuf can assuredly be a preening, condescending, and self-aggrandizing schmuck at times. And for every twinge of conscience Cogburn displays, he definitely has his darker side too, and especially once the bottle gets involved. (Just ask the Indian kids he sadistically pummels for taunting a mule.)

Mattie ultimately finds her quarry are multifaceted folk too — However mangled his teeth, Lucky Ned Pepper in particular has a weird streak of nobility about him. Heroes can be dastardly and villains can be chivalrous: It’s the type of real-life nuance that the Old West shows of Mattie’s later life, with their white hats and black hats, could never quite capture properly. And it’s one of the many truths she learns over the course of her occasionally harsh adventure — her coming-of-age in the last days of the West. (As the aforementioned ursine dentist attests, there are shades of Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man here too.)

True Grit isn’t my favorite Coen movie. That remains Miller’s Crossing. And it’s not my second favorite Coen either — There, the Dude still abides. But like No Country, A Serious Man, and Fargo, True Grit — even after only one viewing — seems like another top-shelfer from the brothers and one of the best films of the year. May they continue to ride high.