“Hmm, good question, Ted. Let me take a crack at it in the long-winded, digression-filled, multiple-answer manner we’ve been trained into. 🙂

First, while I don’t think he’s entirely comfortable with the Sandelian argument I’m making here, our mutual advisor posits one answer to this question in The End of Reform: This all began in earnest during WWII, when two things occurred. [1] The financial and productive power of Big Business became absolutely integral to the success of the war effort (thus there was less of a rationale for opposing corporate power in political life), and [2] Politicians and economists discovered in boom times and Keynesianiam that they could “grow the pie,” economically speaking, rather than be forced to choose a best way to carve it up. So, the civic-minded questions of political economy that dominated the early New Deal fell by the wayside.

Obviously, Adlai and the brothers Kennedy come after WWII, so that in itself is not a complete answer. So I’d add the following trends:

* 1968. Like 1919-1920, when the strike wave, the race riots, the Red Scare, the failure at Versailles, and various other traumatic events — the tail-end of the influenza wave, the death of TR, the Black Sox scandal, the widespread exposure to Freudianism, Einstein’s theory of relativity, and literary/artistic modernism, the recent Bolshevik revolution, and the Great War itself — all conspired to create great anxiety and help overturn the existing order, I would argue that the events of 1968 irrevocably rent the social fabric of the nation.

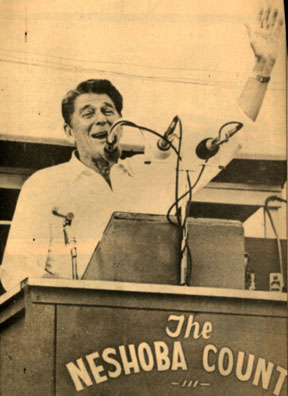

It became especially hard for anyone after ’68 to talk about a civic project or a common public interest when America was divided so badly between left and right, black and white — rifts that Republicans like Nixon and Reagan would exploit to their advantage with the Southern strategy and veiled rhetoric about “law and order” — particularly when those leaders who did it best were gunned down in their prime. (This “culture war” is one of the same obstacles the progressives face in the ’20s, with the Red Scare, Scopes, Prohibition, the KKK, etc.) It also became problematic to speak in the language of citizenship when it was now well beyond clear that [a] women, African-Americans, and other minorities had been and were being treated in the civic culture as second-class citizens, and [b] the main civic project which the government was then asking its citizens to become engaged in was the war in Vietnam, which didn’t make a whole lot of sense.

* GENERATIONS. While both the early New Left (see the Port Huron Statement) and the early civil rights movement (see King, in the original entry) have strong civic, and even Emersonian, components, both Sixties protest groups and the general mood of politics eventually swung over into the rhetoric of individualistic, rights-based liberalism. Meanwhile, the New Right, in its opposition to the New Deal and Great Society, also abandoned to a large extent the language of citizenship and virtue and made an appeal based on individual freedom as opposed to a corrupt, socialistic central government. (For an excellent civic-conservative reaction to this shift, see George Will’s 1983 book Statecraft as Soulcraft, the best thing he’s ever written.)

Stevenson and the Kennedys were of the WWII generation, and — while I loathe the term “greatest generation,” unless you find something inherently great about training fire hoses on small children — they were more comfortable with the civic, “we’re all in it together” appeal of an earlier time. The appeal held less water with the much more skeptical Boomer generation, and, as the political culture embraced the individualistic liberalism/liberation of the late sixties and early seventies, with the nation at large. (You could argue Carter tried to make a civic argument on the energy question, and he was basically laughed out of the room.) Boomer politicians of either party — the Clintons, the Bushes — just aren’t as comfortable making civic-minded, public-interest arguments as their forbears. It’s not how they see the game is played. This is also due to:

* WATERGATE, GATEGATE. From Vietnam to (particularly) Watergate to bureaucratic bloat to Iran-Contra to the fiascos of today, Americans have experienced a severe diminuition in what we believe government is and should be capable of. This open-eyed skepticism about centralized power should be a good thing, but not if we throw out the baby with the bathwater. You know how Richard said “a withdrawal in disgust is not the same as apathy?” Irony isn’t only the shackles of youth, it’s the shackles of our politics as well.

There’s other things going on too. Not to get all Caro up in here, but LBJ, I think, was inherently uncomfortable making civic arguments as well (unless he was appropriating them, a la “We shall overcome.”) His view, shaped as it was by the exigencies of local Texas politics and his days running the Senate, was that everything ultimately boiled down to self-interest. (This partly explains how he could screw up Vietnam so badly. Eventually he thinks about buying off Ho Chi Minh with a TVA-style system of dams for the Mekong Delta, not realizing that Ho — and North Vietnam — are persevering in part because they’ve committed to an ideal more important to them then self-interest: national independence, a cause they felt they’d been fighting for for thousands of years.)

But, perhaps most important to note, I think it’s fair to say that one reason the rhetoric of citizenship went out of style was because:

* THE PATTERN WAS FLAWED, for all the reasons I said above. If I was a guy growing up in Chicago, Mississippi, or anywhere else, and I was being treated as a second-class citizen by the white power structure, either by being denied the right to vote or being snubbed out of quality jobs or housing, and then I was told my civic duty was to go die in Southeast Asia for lousy reasons (while the Dick Cheneys of the world piled up deferments), I might turn against the civic project too. If I was a woman who was told my civic duty basically amounted to finding a good man, keeping his stomach full and his house clean, and punching out healthy, patriotic American children, I’d rebel against this flawed social order as well.

In short, the post-WWII, Cold War-obsessed civic culture of the 1950s and early 1960s was stifling and half-baked. It basically told citizens that their civic obligation was to buy as much as possible, to not consort with Reds, and, most importantly, to not cause any trouble. It needed to be broken up and reconfigured.

(The progressives of the 1920s come to this conclusion as well, when they see how easily Wilsonian public-interest rhetoric enables the Red Scare (thus letting people on the Right brand every possible progressive program as “Bolshevik.”) This is why some of the most civic-minded Progressives — Jane Addams, for example — play a major part in the creation of the ACLU.)

Here we get to the inherent problems with arguments that rely on civic-mindedness and appeals to citizenship. For one, a public interest that treats certain citizens as second-class is inherently and fatally flawed. Look at the early New Left — for all its progressive inclinations and civic-mindedness on paper and even in practice, it still basically treated women like the help. (See SNCC and Stokely Carmichael: “The only position for women in SNCC is prone.“)

Plus, as a general rule of human nature, groups of people working together tend to desire conformity and despise independence, no matter what their political inclinations. This is as much a failing of the Left as it is the Right. (See Animal Farm, Dylan plugging in at Newport, etc.)

Also, here the coercion problem in civic strands of political thought rears its head — Rousseau’s social compact forcing people to be free, and all that. An argument made on the basis of citizenship presumes coercion — citizens are expected to do this (vote, serve in the military, be informed about public matters) and not do that (drink, hang with Communists, etc.) Coercion isn’t necessarily a problem in and of itself — I think everyone agrees citizens should not kill, own slaves, etc. — but [1] telling people they have to do anything goes against the view of absolute individual freedom enthroned today, and [2] coercion invariably leads to conformity. which is ultimately the avowed enemy of republican government, which both relies on and should promote individual excellence.

How do we get around this Gordian knot? My answer (which, not surprisingly, was also the answer of many of the Progressives) rests with Emerson. As I just said, an argument based on citizenship presupposes inculcating a certain virtue into citizens. But what if that virtue was individuality (not the same as individualism) and independence? The ability to think for oneself, the freedom to grow and innovate, and then the inclination to come back to the circle of citizens, share what you’ve learned, and deliberate about the public good? Emerson argues that we express our consent to government by expressing our dissent with government. If republican government is going to reach its full potential, it needs a community of independent-minded nonconformists. This is the type of citizenship a progressive candidate could and should get behind.

And the Progressives did promote it — People always read Herbert Croly as an apologist for strong, centralized government, but this isn’t quite right. Decades before he got into poltics, Croly was an architecture critic — he was deeply concerned about art and aesthetics, and was trying to fashion a political architecture that would help individuals to thrive. At the end of The Promise of American Life (p. 414), Croly talks about what’s he’s been aspiring to create: “A national structure which encourages individuality as opposed to mere particularity is one which creates innumerable special niches, adapted to all degrees and kinds of individual development.” For him the “Jeffersonian ends” of individuality and improvement were as important as the “Hamiltonian means” of a strong central government.

Ok, to step away from Planet Theory and get back to our real world: How would progressive-minded candidates of today work towards this new civic fabric? Well, first and most importantly, they would have to reconceive today’s liberal arguments in civic, progressive terms, to stop using the language of consumer choice and individual freedom — which plays so easily into the hands of corporate power and the small-government Right — like a crutch and bring back the language of citizenship and a shared narrative/vision/history that brings people together. The civic idea is so desiccated at the moment, for all the reasons mentioned in the original post, that just hearkening to its continued existence would be an immense step in the right direction (as well as a huge political boon for the Left regardless.)

From there, progressives, like their counterparts a century ago, would have to work to fix a broken system. This means campaign finance and lobbying reform, doing what we can to ensure that unwashed money doesn’t corrupt the system as horribly as it does now, and that dollars don’t speak louder than people.

As important here is voting reform. The voting system in our nation is absolutely abysmal. I refuse to believe that a country that can give almost every supermarket or store an ATM and almost every person a cellphone and iPod must be reduced to semi-functioning punchcard booths or electronic voting that can’t create a paper trail. And the long lines we see on every election day are patently shameful. Election Day should be a holiday (why not?), we should move to weekend voting, we should establish a Marshall plan to get every county in America an operating voting system, or something. Also, I doubt mandatory voting would ever work in this country, but what about tax incentives, or more likely public-private partnerships to encourage turnout? (Thanks for voting — here’s your free sundae at McDonalds and 20% off your next purchase at Borders.) The people who say this would be tantamount to bribing folks to vote are usually the people who don’t want voters showing up at the polls.

Today’s progressives should also look to education. The (Bill) Clinton model of adult, lifelong education is a step in the right direction, but what’s missing is the civic component. Civics is deader than dead in our high schools and colleges, so on the most basic level that needs to be emphasized. But, equally importantly, we need to reemphasize the skills key to republican government: critical thinking, deliberation, etc. (Dare I say it, reading.) From an early age we all need to learn how to sift through information to reach a critically informed opinion, to ask the right questions about the information being presented to us, and — perhaps most importantly — to learn how to engage with people who disagree with us in a constructive fashion.

And, a civic-minded progressive would continually look to our shared past and our shared future to bring Americans together. This would mean not only basking in but owning up to our collective past — say, adding a National Museum of Slavery to the Mall. It would also mean engaging in great civic projects which would bind the nation in common purpose (one of the many reasons I believe in the necessity of the space program.)

Some might argue that I’m on crack for thinking that campaign finance reform, civics classes, a slavery museum, and/or a trillion-dollar space program is going to change what’s wrong with America. And, no, these aren’t sufficient. But, as I said in the original post, the story is everything. If our leaders help us reconceive our view of the government — to remind us that the government is an expression of our shared values and ambitions as citizens — then we can begin to look at other problems differently. If we’re all in it together, the continued existence of child poverty, or the woeful lack of health insurance for many, here in the richest nation on Earth becomes that much more unacceptable.

I’m not naive enough to believe that embracing civic progressivism or adopting the rhetoric of citizenship is going to change the country immediately, that money is suddenly going to disappear from our political process thanks to one new law, or that the next iteration of American’s civic fabric will be bereft of the types of discrimination in evidence in the 1860s, 1920s, 1960s and beyond. But, to borrow from Cornel West, “To understand your country, you must love it. To love it, you must, in a sense, accept it. To accept it as how it is, however is to betray it. To accept your country without betraying it, you must love it for that in it which shows what it might become. America – this monument to the genius of ordinary men and women, this place where hope becomes capacity, this long, halting turn of the no into the yes, needs citizens who love it enough to reimagine and remake it.“

To put the same argument another way, there’s a scene in The Princess Bride where our hero Westley (Cary Elwes) and the princess Buttercup (Robin Wright Penn) are on the run and looking for safety in the dastardly and invariably fatal Fire Swamp. “We’ll never survive,” bemoans Buttercup, to which Westley responds: “You’re only saying that because no one ever has.” That pretty much sums up how I feel about a lot of things, including progressivism in politics. Does true love exist? I dunno. Lord knows it hasn’t seemed like it, and I’ve been kicked in the teeth often enough at this point to think not. But that doesn’t mean I shouldn’t live my life as if it could happen. Same with this view of civic progressivism. David Greenberg may be right that civic-minded candidates have done pretty poorly in recent history, but that doesn’t mean the principle is flawed, or that we should stop trying.

And, besides, to jump over to another fantasy classic, you don’t wear the ring — you destroy the ring. So I’d rather stake my claim with the public interest progressives, even if that doesn’t play as well as all the blatant appeals to self-interest, than get all Boromir up in here and start acting like Republican-lite, which all too many of our party frontrunners have been doing these past few years.