“The message in The Lord of the Rings is, in a way, that the struggle to destroy the evil also destroys the good. The very effort to mobilize against the evil unalterably changes what you’re trying to defend. So at the very end of that trilogy, the heroes — Frodo the Hobbit, Gandalf and Elrond — sail away. They can’t live in this world that they’ve created, because it’s so different from what they started out to defend. It’s a metaphor; Abraham Lincoln didn’t sail away, he was killed, but the world after the Civil War was not Lincoln’s America anymore.” By way of a friend in the program, Columbia’s Eric Foner picks his five most personally influential books, and guess what made the list…

Tag: Civil War

First Batty, now Booth.

Beware the finger of death, Confederate conspirators. Former fugitive, scoundrel, and president Harrison Ford is slated to track down Lincoln’s assassin in the forthcoming film Manhunt. Ford will play Everett Conger, the retired cavalry officer who helped catch John Wilkes Booth at the Garrett farm, near Port Royal, Virginia, twelve days after Lincoln’s shooting.

Foote-notes.

“The academy never wholly embraced Foote (who, for his part, never considered himself a professional historian or a military expert). Some historians complained that Foote didn’t pay enough attention to the political and economic factors behind the war. Others were offended that he’d dare to write history without footnotes. Looking back, was it merely a case of Northern empiricism scorning Southern charm?” New Yorker editor Field Maloney assesses the historical contribution of — and controversy over — the late Shelby Foote.

The Better Angels of our Nature.

“My favorite portrait of Lincoln comes from the end of his life. In it, Lincoln’s face is as finely lined as a pressed flower. He appears frail, almost broken…It would be a sorrowful picture except for the fact that Lincoln’s mouth is turned ever so slightly into a smile. The smile doesn’t negate the sorrow. But it alters tragedy into grace. It’s as if this rough-faced, aging man has cast his gaze toward eternity and yet still cherishes his memories–of an imperfect world and its fleeting, sometimes terrible beauty.” Senator Barack Obama waxes eloquent on Abe. Worth reading in its entirety. (Via Cliopatria.)

McMonticello.

“‘I think there is more significant history in this corridor than in any comparable space in America,’ Moe said. ‘There’s been a lot of encroachment already, particularly in the form of residential development. If this continues, the character of this region will be changed forever.’” Richard Moe of the National Trust for Historic Preservation adds the expansive Tri-State region between Gettysburg and Monticello to its list of most endangered historical sites.

Kinsey on Lincoln.

Schindler, Rob Roy, Darkman, Qui-Gon, Kinsey…why not Honest Abe? Liam Neeson is apparently in talks to play Lincoln in a Spielberg-directed biopic, to be based on Doris Kearns Goodwin‘s forthcoming book, The Uniter. Ok, that’s not bad…but hopefully this project turns out better than Amistad.

Also in loosely related Lincoln-by-way-of-Kinsey news, Salon‘s Andrew O’Hehir casts a troubled eye at C.A. Tripp’s Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln. As he ably points out (as does George Chauncey in the excellent Gay New York), “the difficulty with assessing Lincoln’s private life (or that of anyone else who lived before the 20th century) is that the nature of private life has changed dramatically from his time to ours, and the distance between us distorts the view…Whether [Lincoln and Joshua Speed’s, with whom Lincoln shared a bed] relationship had a sexual component or not, it belongs to a vanished world of intimate male friendships of a kind almost unrecognizable to us.” In other words, sexual orientation is an historically dynamic idea. Homosociality does not necessarily imply homosexuality, and one cannot simply read 19th century sources and infer a 20th century mindset. You have to delve a little deeper. Update: Columbia’s David Greenberg also weighs in for Slate.

The Battles Rage On(line).

“My dear McClellan: If you don’t want to use the Army I should like to borrow it for a while.” Good news for Civil War reenactors and military history enthusiasts: The Library of Congress, the Virginia Historical Society, and the Library of Virginia are posting over 2240 CW-era maps and charts online. (AP Story here.)

Desolation Row.

For the historians and Dylanologists out there (or for those wondering why Dylan would contribute a new song to a flat-out stinker like Gods and Generals), here’s another intriguing passage from Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, on his early days in the archives as a Civil War enthusiast. (Besides Clausewitz, he also professes an admiration for Reconstruction-era Republican Thaddeus Stevens, who “championed the weak” and “made a big impression on me,” in a separate passage. (Chronicles, p. 40))

“I couldn’t exactly put in words what I was looking for, but I began searching in principle for it, over at the New York Public Library, a monumental building with marble floors and walls, vacuous and spacious caverns, vaulted ceiling. A building that radiates triumph and glory when you walk inside. In one of the upstairs reading rooms I started reading articles in newspapers on microfilm from 1855 to about 1865 to see what daily life was like. I wasn’t so much interested in the issues as intrigued by the language and rhetoric of the times. Newspapers like the Chicago Tribune, the Brooklyn Daily Times, and the Pennsylvania Freeman. Others, too, like the Memphis Daily Eagle, the Savannah Daily Herald, and Cincinnati Enquirer.

It wasn’t like it was another world, but the same one only with more urgency, and the issue of slavery wasn’t the only concern. There were news items about reform movements, antigambling leagues, rising crime, child labor, temperance, slave-wage factories, loyalty oaths and religious revivals. You get the feeling that the newspapers themselves could explode and lightning will burn and everybody will perish. Everybody uses the same God, quotes the same Bible and law and literature. Plantation slavecrats of Virginia are accused of breeding and selling their own children. In the Northern cities, there’s a lot of discontent and debt is piled high and seems out of control.

The plantation aristocracy run their plantations like city-states. They are like the Roman republic where an elite group of characters rule supposedly for the good of all. They’ve got sawmills, gristmills, distilleries, country stores, et cetera. Every state of mind opposed by another…Christian piety and weird mind philosophies turned on their heads. Fiery orators, like William Lloyd Garrison, a conspicuous abolitionist from Boston who even has his own newspaper. There are riots in Memphis and in New Orleans. There’s a riot in New York where two hundred people are killed outside of the Metropolitan Opera House because an English actor has taken the place of an American one. [Sic — 23 dead. Bob’s probably conflating the 1849 Astor Riot with the 1863 Draft Riots.] Anti-slave labor advocates inflaming crowds in Cincinnati, Buffalo, and Cleveland that, if the Southern states are allowed to rule, the Northern factory owners would then be forced to use slaves as free laborers. This causes riots, too.

Lincoln comes into the picture in the 1850s. He is referred to in the Northern press as a baboon or giraffe, and there were a lot of caricatures of him. Nobody takes him seriously. It’s impossible to conceive that he would become the father figure that he is today. You wonder how people so united by geography and religious ideals could become such bitter enemies. After a while you become aware of nothing but a culture of feeling, of black days, of schism, evil for evil, the common destiny of the human being getting thrown off course. It’s all one long funeral song, but there’s a certain imperfection in the themes, an ideology of high abstraction, a lot of epic, bearded characters, exalted men who are not necessarily good.

No one single idea keeps you contented for too long. It’s hard to find any of the neoclassical virtues, either. All that rhetoric about chivalry and honor — that must have been added later. Even the Southern womanhood thing. It’s a shame what happened to the women. Most of them were abandoned to starve on farms with their children, unprotected and left to fend for themselves as victims to the elements. The suffering is endless, and the punishment is going to be forever. It’s all so unrealistic, grandiose, and sanctimonious at the same time.

There was a difference in the concept of time, too. In the South, people lived their lives with sun-up, high noon, sun-set, spring, summer. In the North, people lived by the clock. The factory stroke, whistles and bells, Northerners had to “be on time.” In some ways the Civil War would be a battle between two kinds of time. Abolition of slavery didn’t even seem to be an issue when the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter. [Sic! Tell that to John Brown or Alexander Stephens. To be fair, though, elsewhere in Chronicles (pp. 74, 76), Dylan notes other theories for the war’s coming.]

It all makes you feel creepy. The age that I was living in didn’t resemble this age, but yet it did in some mysterious and traditional way. Not just a little bit, but a lot. There was a broad spectrum and commonwealth that I was living upon, and the basic psychology of that life was every bit a part of it. If you turned the light towards it, you could see the full complexity of human nature. Back there, America was put on the cross, died, and was resurrected. There was nothing synthetic about it. The godawful truth of that would be the all-encompassing template behind everything that I would write.

I crammed my head full as of much of this stuff as I could stand and locked it away in my mind out of sight, left it alone. Figured I could send a truck back for it later.” {Chronicles, pp. 84-86 — emphasis and paragraph breaks mine.)

President’s Day 2004

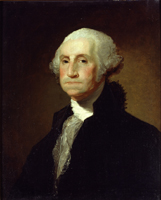

“As the sword was the last resort for the preservation of our liberties, so it ought to be the first to be laid aside when those liberties are firmly established.” – George Washington

“The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise — with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.” – Abraham Lincoln

A Frigid, Starry Peak.

Well, I haven’t read the Charles Frazier novel, but I’d say “Cold Mountain” is an apt and colorful metaphor to sum up this film, its stars, and even its director’s entire body of work. For like Nicole Kidman and Jude Law, and as with The English Patient and The Talented Mr. Ripley, Cold Mountain is beautiful but distant, occasionally breathtaking but often chilly, and not so much high as just plain stilted. In fact, the hike up and down this Cold Mountain includes definite moments of grandeur, but more often than not it feels like a bit of a slog. At times, it’s even glacial.

I should say up front that this is a far better Confederate-centered Civil War film than the vile Gods and Generals. The chaos and carnage of the Battle of the Crater that opens the film seems much more real and visceral than anything in the godawful G&G. Whatsmore, the historical aspects of Mountain generally feel right (In fact, much of the film seems like a fictionalization of Drew Gilpin Faust’s Mothers of Invention, which vividly describes how the lives of Southern women were transformed by the war experience and the collapse of the Confederate patriarchy.)

Unfortunately, the respectable versimilitude of the film keeps getting undermined by the wattage of its star power. From Stalingrad to Petersburg, nobody in the business does starving-but-handsome-and-resolute-warrior as well as Jude Law these days, and he’s quite good here despite the frequent accent-slippage. But, frankly, Nicole Kidman feels all wrong here. It’s not that she’s bad per se, it’s just that, like her ex-husband in 19th-century Japan three weeks ago, she never seems like she fits this milieu at all. (It doesn’t help that she spends most of the end of the film in an outdoor outfit that looks Banana Republic-coordinated.) Finally, others have noted the lack of chemistry between Law and Kidman, and I too thought the central romance here was rather uninvolving.

But, even if the two leads’ remarkable frigidity wasn’t distracting enough, Law and Kidman are just the tip of the iceberg. In fact, in the spirit of the film, I’ll go ahead and torture this metaphor even further…Perhap sensing that the romantic low burn here might be too dim a fire to heat the screen for 150 minutes, Anthony Minghella has packed Cold Mountain so full of stars and cameos that it starts to feel like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. From Lucas Black getting bayonetted in the opening minutes to Jack White procuring cider at the very end (in yet another of Minghella’s quintessentially ham-handed symbolic moments, but I’ll get to that later), famous faces keep appearing around every corner of the poor, white backcountry South, and it took me out of the movie almost every time. Basically, I found it hard to become engrossed in the film when I kept thinking things like “So, that’s what Kathy Baker‘s been up to…she got married to the manager from Major League,” “James Rebhorn‘s his doctor? He’s toast,” “Well, Jena Malone didn’t last very long,” “and “Hey, that’s Cillian Murphy. Between him and Brendan Gleeson, this is like a sequel to 28 Days Later…um, except it has no zombies and it’s set in the Civil War South.”

Ok, perhaps that’s an unfair criticism, but I’d think even people who don’t go to the movies much are going to be distracted by all the Hollywood faces flitting about. I should say while I’m on the subject that Brendan Gleeson is very good (as always) here – Not only does he handle the accent like a champ, but he conveys more emotion in one winsome smile or knowing grimace than many of the central characters do the entire film. As for other good performances…Despite lugging around a baby that’s as big as she is, Natalie Portman proves here that she can still act when not forced in front of a bluescreen. (By the way, after the Portman episode, why didn’t Inman take one of the Union horses?) Giovanni Ribisi moves into the frontrunning for the Cletus the Slack-Jawed Yokel biopic. And, Renee Zellweger…well, she moons and mugs through this film like a Best Supporting Actress award was her birthright, but she still gives Cold Mountain a very-much-needed jolt in the arm every time she shows up. (She’s particularly energetic when compared to the staid Kidman.)

On the flip side of the coin, somebody should’ve told Donald Sutherland that different parts of the South call for different accents…he sounds miles away from a Charlestonian. And Phillip Seymour Hoffman, perhaps the best thing about Minghella’s Ripley, is perhaps the worst thing about Cold Mountain. Completely unconvincing in his role here, he’s a walking, talking anachronism.

All the unnecessary star voltage aside, of course, this movie eventually rises and falls on its director, and all of Anthony Minghella’s strengths and weaknesses are present here. (I should say that I loathed The English Patient and enjoyed Ripley until Jude Law was killed, after which the film meandered to its conclusion.) Both Patient and Ripley have some very beautiful and striking moments, but more often than not the imagery is so “artfully” composed as to become hamhanded. The same goes here for Mountain…we’ve got a lamb running around in wolf’s clothing, we’ve got a dove trapped in a church until Jude Law sets it free (you do the math)…in fact, we have enough fluttering, portentous birds on a wing here to make John Woo blush. Perhaps these capital-S Symbols are in Frazier’s novel too, but I’d still think a subtler director could have mined them more dexterously. And, while I didn’t know the ending coming in, Minghella foreshadows the conclusion so laboriously (even having Kidman break it down step-by-step to Zellweger) that I spent the last twenty-five minutes just waiting for the other shoe to drop, which killed any real emotion I might’ve felt about the denouement.

Looking back, I’ve been pretty harsh here, so I should repeat that Cold Mountain is not a bad film at all. In many ways, it’s quite good. But, Oscar buzz notwithstanding, it’s definitely not great…in fact, I even found it less involving than The Last Samurai. In the future, were I looking to recommend a film that captures the despair and devastation afflicting the Confederate homefront in the waning days of the war, I just might pick Cold Mountain. But, as for attempts to give The Odyssey a Faulknerian palmetto-and-spanish-moss recasting, give me O Brother Where Art Thou? any day of the week.