The Monuments Met.

Haunting the Web Since 1999

By way of a friend, the Oval Office gets some Hoppers on loan (apparently to replace a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation, which needs to get out of the light for awhile.) “Cobb’s Barns, South Truro, and Burly Cobb’s House, South Truro — oil on canvas works painted in 1930-33 on Cape Cod — have been lent by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the world’s largest repository of Hopper’s works.”

Also by way of The Late Adopter: With Edward Hopper as his (original) inspiration, photographer Richard Tuschman conjures up evocative Hopper-style photos using dioramas and Photoshop. “I have always loved the way Hopper’s paintings, with an economy of means, are able to address the mysteries and complexities of the human condition,’ Tuschman wrote in his statement about the work.”

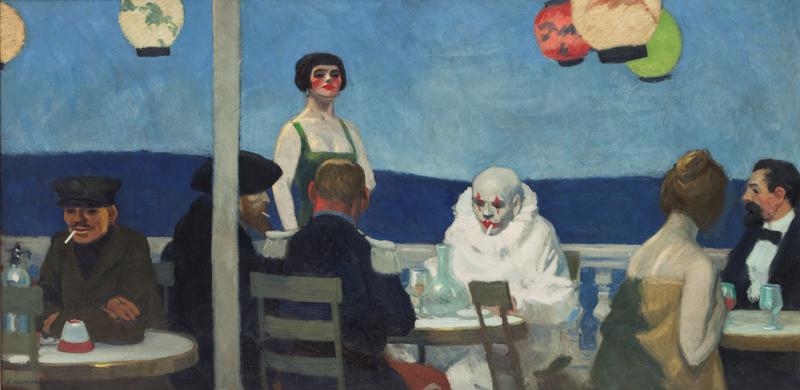

In the Observer, college friend Maika Pollack surveys the Edward Hopper retrospective at the Whitney. “He painted the quality of light with adjectival precision-cool electric light, thin morning light, the lonely light from a cinema screen. (If Hopper loved movies, the movies loved Hopper back: In his House by the Railroad [1925], we see the inspiration for Hitchcock’s Bates Motel in Psycho).”

“Sexual tension is at the heart of Hopper’s Room in New York, a scenario we peer at through an open window. Home from work, the man reads the sports page. Dressed to go out, the woman plays a single note on the piano, knowing it will annoy him. Their faces are almost as featureless as the blank sheet of music on the piano. Separated by the abstract expanse of the tall brown door, they are literally out of touch. But look a little closer at that fleshy pink armchair…Doesn’t that pink chair look unsettlingly like a huge hand, a jutting thumb and curled fingers, ready to clutch the unsuspecting man from behind and give him a shake? Is this the woman’s fantasy?“

Mount Holyoke English professor Christopher Benfey surveys “Edward Hopper’s secret world” for Slate, commenting at length on a painting whose iconography I’ve been shamelessly pilfering for years here, at the personal site, and elsewhere. Interesting…I always felt the picture captured a state of anomie and self-inflicted loneliness more than it did sexual tension — It’s a furtive through-the-window look at two people crammed into a tiny little room in New York basically ignoring each other. Or, more to the point, the man at left, caught up in the newspaper (news, not sports!) is so distracted by the world at large that he’s shut out his neglected lover at the piano: In his attention to distant events, he’s missing out on the beautiful things in his own life. But, hmm, that chair…

“Even before he had established himself as a delineator of New York places, the artist had already pinpointed a New York state of mind. That state is not so much ‘loneliness,’ as the maudlin cliche about him would have it, but a tougher and more unsparing isolation that touches on the traps of modern urban existence, one in which individuals must become inured to life’s insults and injuries.” Art critic Avis Berman previews her new book on Edward Hopper’s New York for the Sunday Times.

“Even before he had established himself as a delineator of New York places, the artist had already pinpointed a New York state of mind. That state is not so much ‘loneliness,’ as the maudlin cliche about him would have it, but a tougher and more unsparing isolation that touches on the traps of modern urban existence, one in which individuals must become inured to life’s insults and injuries.” Art critic Avis Berman previews her new book on Edward Hopper’s New York for the Sunday Times.