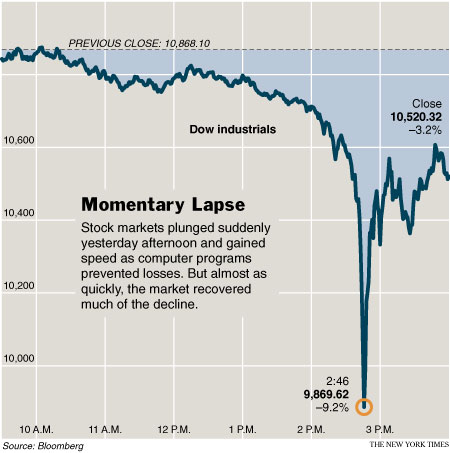

In fact, what they did was violate one of the prime rules of trading: never try to catch a falling knife. The market was falling fast and furious at the point they entered the pit to buy equity futures, so why did they take such an enormous risk? We learned yesterday that both of these firms, plus Goldman Sachs, were such superb traders in the market that none of them had a single losing trading day all last quarter. This type of risky trade is not how you get to be a superb trader.

“Over at the Agonist, Numerian digs deep into last week’s “Flash Crash” — and comes to some very troubling conclusions. To wit, the big players know the thresholds where the trading algorithms kick in, and thus, basically, the fix is in. “The stock market seems to be nothing but a playground for the big banks and other connected firms who get a preview peek at everything that goes through the market, and who can program their computers to skim profits off daily with no risk whatever. The stock market is also, quite possibly, prone to more serious manipulation that resulted in last Thursday’s crash.“

Oof. I’m out of my comfort zone when it comes to understanding market behavior, so I hope someone has a better explanation for the Flash Crash than the disconcertingly plausible one offered here. (Just saying Greece doesn’t quite cut it, I don’t think.)