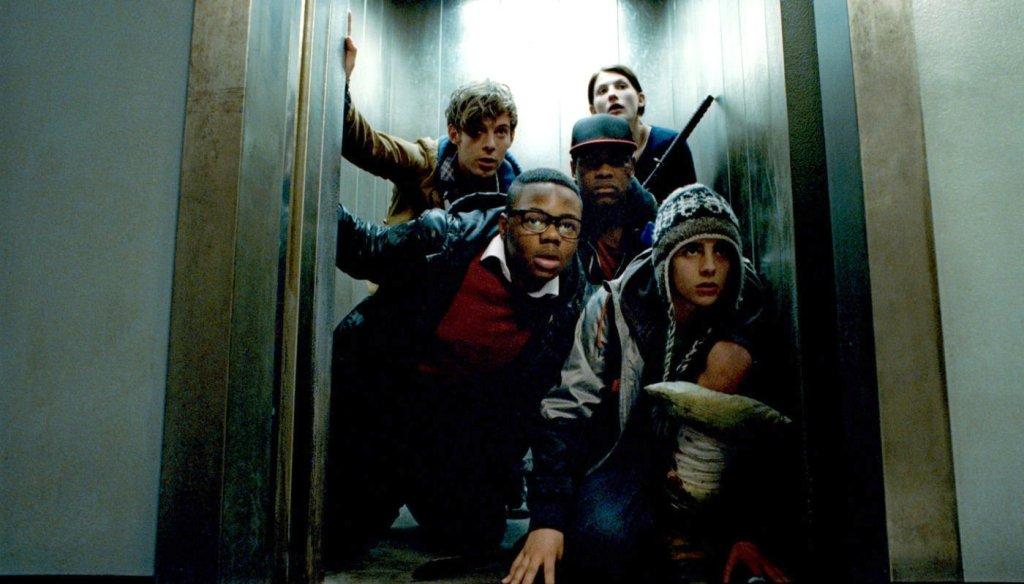

In the opening moments of Martin Scorsese’s ambitious, expertly-crafted, and, alas, strangely sluggish Hugo, we are transported to a snowy winter’s evening in 1931 Paris at the Gare Montparnasse, where an orphan boy (a Frodo-ish Asa Butterfield) named Hugo Cabret watches the train station crowds from behind a clock face. He eyes the station guard (Sasha Baron Cohen), the flower girl (Emily Mortimer), the socialite (Frances de La Tour), her potential paramour (Richard Griffiths), the ancient bookseller (Christopher Lee). And as flakes of snow whirl about in three dimensions and a haunting Howard Shore score perfectly evokes the melancholy elegance of Parisian yore, we see young Hugo eventually hone in on the toy stand of a despondent old man (Ben Kingsley.)

Who is this old man, and how his fate bound up with Hugo’s? That is the question that drives this historical fairy tale (formerly Brian Selznick’s The Invention of Hugo Cabret.) What follows is a child’s adventure story, a fantastic and whimsical tale of movie history bound up in the love of film itself, and an exercise in 3D innovation forged by a master craftsman with clockwork precision and…ok, let’s take a breath here. At the risk of opening myself to charges of pearls before swine, can I actually just confess to being a little bored by Hugo?

Mind you, I’m not happy about it: I love movies, i like historical fantasy. By the syllogistic principle, I should adore a historical fable about loving movies. In addition Hugo is an exceedingly well-made entertainment, and I presume it works reasonably well as a family film for Potter-inclined children of a certain age and temperament. (Although, frankly, I could imagine a lot of kids being bored too.) And every time some new character popped into the story, it was almost always an actor or actress — Chloe Moretz, Ray Winstone, Michael Stuhlbarg — that I’m fond of watching. But it’s a plain fact that, however entrancing Scorsese’s second- and third-act invocations of Georges Melies — the cinema’s first imagineer, as it were — I watched Hugo feeling mostly disengaged from it.

In the interests of full disclosure, while thinking over the reasons for how this clinical distance might’ve happened, it occurred to me after the fact that I have felt much the same about almost every other one of Martin Scorsese’s films. I’m not saying the man’s a hack or anything — He’s clearly an exceptional craftsman and a deservedly historic figure among American directors. But from his early classics (Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, all of which I saw on VCR years after they came out) to Goodfellas (which, to be fair, I caught after The Sopranos) to his recent run of films (Gangs of New York, The Aviator, Shutter Island, The Departed), I’ve had almost the same reaction in the end to every one of his films: Well that was well-put-together, but not very emotionally engaging. (The one major exception here, and my favorite Scorsese movie, is The Last Temptation of Christ, although I also quite like Casino and The King of Comedy. Update: And Kundun, After Hours, and The Age of Innocence as well, now that I think more on it.)

The other issue at work here is the issue of the Third Dimension. Over the course of its run, Hugo — a movie which eventually discusses the earliest days of the cinema — not very subtly makes a case that we are witnessing a similar birth of a new art form right now, with 3D technology. (After showing us the Lumiere brothers’ 1895 film of an arriving train, which scared audiences untrained in film-watching into thinking they’d be run over, Scorsese recreates the scene at the Gare Montparnasse using 2011’s finest 3D tech.) Now, I know that saying things like “3D movies are just a fad” is exactly the type of statement that will leave one ripe for ridicule down the road. (re: “Talkies will never catch on,” or “Why would we ever need color?“) Buuuuut…I’m still not entirely sure the current 3D boom is anything more than a fad.

Here’s the thing: I’m glad visionary directors like Scorsese, James Cameron, and Peter Jackson are pushing the envelope and the technology on 3D. (For what it’s worth, Cameron says Hugo is the best 3D photography he’s ever seen. I’ll reserve full judgment until I’ve seen The Hobbit at 48 frames per second.) At the same time, it seems to me that, at least at present, 3D is mainly being used as a way to push audiences to continue seeing films on the big screen instead of watching them at home. In other words, it’s a filler technology being used to paper over the gaps at a transitional time for the medium, and its recent embrace has more to do with the business of movies than the art of them.

So, my skepticism about 3D at the moment isn’t really about being a Luddite. If anything, the technology isn’t advanced enough yet. When audiences can see the effect without wearing the damnable headache-inducing glasses, or we move past screen projection to full three-dimensional projection, not unlike the holograms in Star Wars, then I might start to agree we’re in Lumiere or Melies territory. But making movies look vaguely and unnecessarily like pop-up books, or having a ginormous Sasha Baron Cohen head jump out at you rather than the usual arrows and projectiles or whatnot, is not really a game-changing use of the medium, and it seems a bit hubristic to suggest so.

I still submit that the most groundbreaking use of 3D I’ve ever witnessed was in the concert film U2 3D, which layered completely separate images into one field of vision, and thus suggested an entirely new form of cinema syntax. Unfortunately, neither Cameron nor Scorsese have opted to explore that route as of yet. Instead, Scorsese has given us here a fine example of how standard story-telling can be slightly enhanced by 3D. I just wish it wasn’t so ponderous at times. Your mileage may vary, of course, but when I was having reactions during the movie like, “Oh Lord, we’re about to get another ten minutes of Sasha Baron Cohen playing the martinet,” that is just not a good sign.