“

On the surface, an artist tries to frame his ideals in an image, to challenge his audience and make his vision immortal. But the parasites say ‘NO! Your art must serve the cause! Your ideals endanger the people!’ Lacking its own ingenuity, the Parasite fears the visionary. What it cannot plagarize, it seeks to censor; what it cannot regulate, it seeks to ban. Rapture was founded on an idea, and here they are held inviolate.“Hmm…maybe they should’ve moved the Barnes to Rapture, then. Gamers might recognize the rantings above as those of the Ayn Randish industrial magnate

Andrew Ryan, whose

Journey to the Surface amusement ride is

one of the cleverer setpieces in the recently-released

Bioshock 2. But they also reflect the basic conceit within

Don Argott’s Art of the Steal, a rather aggravating documentary about the recent

moving of the Barnes Collection from Lower Merion, PA into downtown Philadelphia.

Art of the Steal starts off as an intriguing albeit confused retelling of this political story: Intriguing in that there’re a lot of interlocking and complicated motivations at work, and confused in that the documentary assumes certain first principles — and, later, malign intent — without backing them up. And while I was willing to forgive Art of the Steal its imbalance for awhile just because it was so clearly compelled by a sense of injustice done, the documentary gradually becomes so grossly one-sided in its telling that it skips right over myopic and naive and ends up feeling downright corrupt.

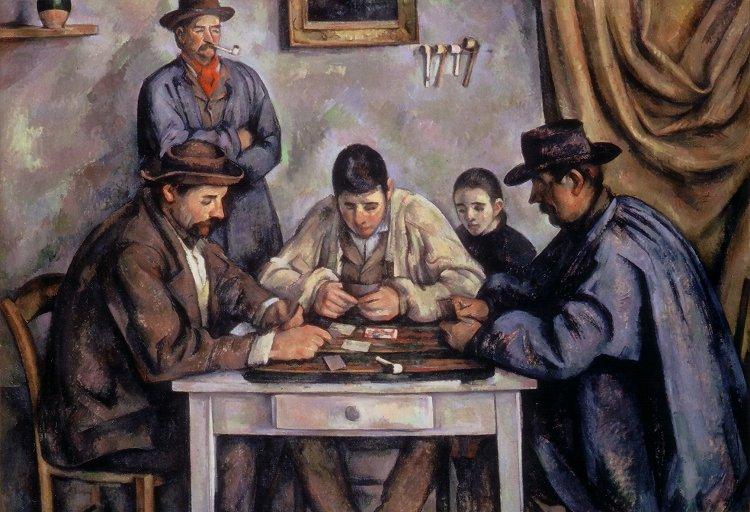

The story of the Barnes begins with the rise of our Andrew Ryan figure, Albert C. Barnes, a forward-thinking, working-class Philadelphian who, by dint of extraordinary intelligence and a hole in the pharmaceutical market, was a millionaire by the time he was 35. Considered a curmudgeon and misanthrope even by his friends, Barnes also had an undeniably great eye for art, and he started buying up masterpieces of the Post-Impressionist and early Modern periods — Van Gogh, Cezanne, Picasso, Matisse — well before any other museums caught on to the scene. And when his attempts to show off his impressive collection in the town of his birth are ridiculed by the stuffy, conventional Philadelphia swells, Barnes angrily vows that he will never show off his private collection to these philistines, ever again.

Barnes is nothing if not a man of his word. He builds his own palatial gallery-school in Lower Merion, a suburb of Philly 4.5 miles outside the city center, and decides to restrict access to his collection to art students, working-class folks, and anyone else he deems worthy. The good news is Mr. Barnes’ sense of worthy is actually pretty keen: Barnes is a New Deal man well ahead of his time, particularly on the race relations front, and he greatly enjoys ridiculing the Philadelphia glitterati, most notably the Yang to his Yin, the conservative-minded Annenbergs. But even the Great Man cannot live forever, and when he dies in a car accident at an advanced age, the scions of Philadelphia begin their slow, convoluted plot to wrest Barnes’ art from him…for the good of the City, of course.

To his credit, Barnes did anticipate thus, and so his will clearly stipulates that this world-historical collection of art never be shown nor removed from its Lower Merion stronghold. (And, as a final screw-you to the Philly elites he loathed, he leaves it as a last resort to the local African-American college, Lincoln.) But, as time passes, and people die off, and Fortress Barnes itself starts to decay from within, the dead man’s ghostly hold over his property becomes more and more attenuated. To the point where — when a case is made that the art would be better off in Philly — well, the Great Man himself has been gone for fifty years, right?

Art of the Steal is at its best in the first hour, when it sets up the personalities involved and recounts the byzantine, death-by-increments process by which the Barnes collection finally got relocated. But, quite frankly, I thought there were some problems with its central thesis from the start. The documentary goes well out of its way to depict the people in favor of moving the collection as despicable and/or corrupt (and it is clear that some of the shadier operators, like Walter Annenberg, were indeed motivated by personal pique). But, nobody ever presents the counter-argument, that maybe (gasp!) there is really a legitimate case for moving the Barnes to downtown Philadelphia.

For one, the Barnes is an impressive building, and one of the best arguments the Barnes disciples make for keeping the collection there is the Great Man’s — again, extremely forward-thinking — methods of curation. (Unlike most museums, Barnes never subdivided the work by period or artist. He grouped by aesthetic, across cultural, geographic, and chronological lines, thus emphasizing a universality of art which is only now becoming more popular in museums.) But round the decay of that colossal wreck, nothing beside remains. For all intent and purposes, the Barnes really did seem to be falling apart, and attempts to continue using Lower Merion as a home base for the collection — adding parking lots and such — were roundly fought off by many of the same locals (Barnes might call them elites) later shown, when it’s convenient, to be “friends of the museum.”

And if the Ozymandias quote didn’t tip you off, I would also argue there’s a world-historical eminent domain question here that should at least be addressed. Albert Barnes may have been a Great Man, but…Mistah Barnes, he dead. (“God rest his soul, and his rudeness. A devouring public can now share the remains of his sickness.“) He’s as dead as King Tut, who probably would not have signed off on what Howard Carter et al did to his tomb. (In fact, I’d argue Tutankhamun almost assuredly got screwed over worse than Barnes.) And, speaking of which, there’s a reason why Indiana Jones’ usually undisputed refrain is, “It belongs in a museum!“

You may disagree, of course, and think that Barnes’ will should be held inviolate from now until the End of Days — Ok, that’s cool, we disagree. But a good documentary would at least entertain this obvious opposing argument. Instead, Art of the Steal keeps making overbroad assertions that merit some serious unpacking. This tale, according to the movie, is a devastating triumph of Unbridled Commerce over the Purity of Art. But wait…wasn’t this about Commerce as soon as Barnes bought the art in the first place? He didn’t paint this stuff. And, according to the movie, the Barnes collection stands for Democracy in the face of the Corporatization of Art. It does? I thought Barnes hated “the mass experience” and wanted to show his collection only to the worthy. That doesn’t sound particularly democratic to me.

And in its final half-hour or so, Art of the Steal just fulminates and rages, barely making any sense at all. It accuses City officials of enacting an elaborate and corrupt scam on the people, and then depicts County officials, as well as the area’s GOP Congressman, as if they’re pure art lovers or something. (Like, I dunno, maybe Lower Merion and Montgomery County, etc., have some financial interests at stake here too?) It accuses the Philadelphia Art Museum’s backers of orchestrating this nefarious plot, but never satisfactorily explains how having a rival art museum moved downtown would benefit them. (Presumably, the argument is a rising tourist tide lifts all boats, I guess. The movie has a better case against the Pew Charitable Trust, who pretty clearly use the Barnes rather dodgily as leverage to improve their tax situation.)

And, with the possible exception of Richard Glanton, an enterprising former Foundation head seen as either the first crack in the Barnes dike or, as he sees himself, Cerberus defending the gates of Hell (Apres moi le deluge), the movie keeps shoehorning everyone involved into either hero or villain, without ever conceding that the issues are more complicated than they first seem. (Julian Bond of the NAACP, for example, is a witness for the prosecution here. But one of his more compelling arguments — that the powers-that-be screwed over Lincoln University, an historically black institution, by Bigfooting them into the move — is mostly elided over.) And the movie generates so much heat in the end that the light is lost. At one point, Governor Ed Rendell says the move of the collection to Philadelphia just seemed like an easy call to him, and after watching this documentary, I didn’t see much to disqualify that claim. Other than following verbatim the will of a man with no heirs who’s been dead for fifty years, what were the reasons again for keeping the collection in Lower Merion?

In choosing to be a one-sided screed rather than an in-depth exploration of the subject at hand, Art of the Steal does its very interesting topic no favors. In the end, the movie works less as a definitive statement on the thorny entanglement of art and commerce than as a sad testament to the narcissism of petty differences. And from the muddled picture one gets of Mr. Barnes here, the Great Man deserved a better advocate.