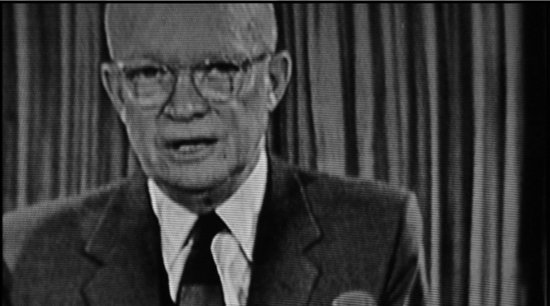

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes.” That flaming liberal Dwight Eisenhower’s somber farewell address to the nation is the historical and thematic anchor for Eugene Jarecki’s documentary Why We Fight, a sobering disquisition on American militarism and foreign policy since 9/11. In essence, Why We Fight is the movie Fahrenheit 9/11 should have been. Like F911, this film preaches to the choir, but it also makes a more substantive critique of Dubya diplomacy and the 9/11-Iraq switcheroo, with much less of the grandstanding that marred Moore’s earlier documentary (and drove right-wing audiences berzerk.)

Sadly, the basic tale here is all-too-familiar by now. Ensconced in Dubya’s administration from the word go, the right-wing think-tank crowd (Wolfowitz, Perle, Kristol, etc.) used the tragedy of 9/11 as a pretext to enact all their neocon fantasies (spelled out in this 2000 Project for a New American Century report), beginning in Iraq. Taken into consideration with Cheney the Military-Contractor-in-Chief doling out fat deals to his Halliburton-KBR cronies from the Vice-President’s office, and members of Congress meekly signing off on every military funding bill that comes down the pike (partly because, as the film points out, weapons systems such as the B-1 or F-22 have a part built in every state), it seems uncomfortably clear that President Eisenhower’s grim vision has come to pass.

To help him rake this muck, Jarecki shrewdly gives face-time not only to learned critics of recent foreign-policy — CIA vet Chalmers Johnson, Gore Vidal (looking unwell) — but also to the neocons themselves. Richard Perle is here, saying (as always) insufferably self-serving things, and Bill Kristol glows like a kid in a candy store when he gets to talk up his role in fostering Dubya diplomacy. (Karen Kwiatkowski, a career military woman who watched the neocon coup unfold within the corridors of the Pentagon, also delivers some keen insights.) And, when discussing the corruption that festers in the heart of our Capitol, Jarecki brings out not only Charles Lewis of the Center for Public Integrity but that flickering mirage of independent-minded Republicanism, John McCain. (In fact, Jarecki encapsulates the frustrating problem with McCain in one small moment: Right after admitting to the camera that Cheney’s no-bid KBR deals “look bad”, the Senator happens to get a call from the Vice-President. In his speak-of-the-devil grimace of bemused worry, you can see him mentally falling into line behind the administration, as always.)

To be sure, Why We Fight has some problems. There’s a central tension in the film between the argument that Team Dubya is a corrupt administration of historical proportions and the notion that every president since Kennedy has been party to an increasingly corrupt system, and it’s never really resolved satisfactorily here. Jarecki wants you to think that this documentary is about the rise of the Imperial Presidency across five decades, but, some lip service to Tonkin notwithstanding, the argument here is grounded almost totally in the Age of Dubya. (I don’t think it’s a bad thing, necessarily, but it is the case.) And, sometimes the critique seems a little scattershot — Jarecki seems to fault the Pentagon both for KBR’s no-bid contracts and, when we see Lockheed and McDonnell-Douglas salesmen going head-to-head, for bidding on contracts. (Still, his larger point is valid — As Chalmers Johnson puts it, “When war becomes that profitable, you’re going to see more of it.“)

Also, the film loses focus at times and meanders along tangents — such as the remembrances of two Stealth Fighter pilots on the First Shot Fired in the Iraq war, or the glum story of an army recruit in Manhattan looking to turn his life around. This latter tale, along with the story of Wilton Sekzer, a retired Vietnam Vet and NYPD sergeant who lost his son on 9/11 and wants somebody to pay, are handled with more grace and less showmanship than similar vignettes in Michael Moore’s film, but they’re in the same ballpark. (As an aside, I was also somewhat irked by shots of NASA thrown in with the many images of missile tests and ordnance factories. Ok, both involve rockets, research, and billions of dollars, but space exploration and war are different enough goals that such a comparison merits more unpacking.)

Nevertheless, Why We Fight is well worth-seeing, and hopefully, this film will make it out to the multiplexes. If nothing else, it’ll do this country good to ponder anew both a president’s warning about the “disastrous rise of misplaced power,” and a vice-president’s assurance that we’ll be “greeted as liberators.”