“‘As expected, after it opened it was elbow to elbow,’ the history says. ‘The comfort women…had some resistance to selling themselves to men who just yesterday were the enemy, and because of differences in language and race, there were a great deal of apprehensions at first. But they were paid highly, and they gradually came to accept their work peacefully.‘” The continuing furor in Asia over Japan’s ignominious use of “comfort women” (re: forced prostitution) during WWII reaches America, as it comes to light that occupation Japan created a similar “comfort system” for American GI’s in the year after the war (until MacArthur shut it down in the spring of 1946.) “An Associated Press review of historical documents and records shows American authorities permitted the official brothel system to operate despite internal reports that women were being coerced into prostitution. The Americans also had full knowledge by then of Japan’s atrocious treatment of women in countries across Asia that it conquered during the war…Although there are suspicions, there is not clear evidence non-Japanese comfort women were imported to Japan as part of the program.”

Tag: History

Only Yesterday.

By way of Ted at The Late Adopter, a bunch of 1940’s D-listers reminisce about the Depression Decade, VH-1 style, in I Love the ’30’s. Hey, isn’t that one of the Sonic guys? (The married one, not these two.)

The Audacity of Tolerance.

“Skeptics derided JFK, as they now do Obama, as callow and ill-versed in substantive issues. And yet Obama, similar to JFK, manages to inspire people with sex appeal, cerebral cool, and a message of generational change.” Rutgers University professor David Greenberg examines the similarities between Senator Obama and President Kennedy, and argues that Obama’s team might just be taking a page from the JFK campaign’s Catholicism playbook with regard to race in 2008. “Having passed a threshold among most white voters, his race can implicitly encourage them to feel that a vote for Obama is a vote for tolerance, for a future free of the constricting prejudices of the past, and for a sense of hope that Jack Kennedy once evoked.“

Tools of the Trade.

Personal plug: A book I worked on last summer, the second edition of Robert C. Williams’ The Historian’s Toolbox: A Student’s Guide to the Theory and Craft of History, has just been published. As the intro notes, I “helped add sections on the internet, event analysis, public analysis, public history, oral history, and material culture.” But, even before those additions, Williams’ book made for an excellent classroom tool for teaching the basics of historiography to undergraduates. I hope it finds some use.

Personal plug: A book I worked on last summer, the second edition of Robert C. Williams’ The Historian’s Toolbox: A Student’s Guide to the Theory and Craft of History, has just been published. As the intro notes, I “helped add sections on the internet, event analysis, public analysis, public history, oral history, and material culture.” But, even before those additions, Williams’ book made for an excellent classroom tool for teaching the basics of historiography to undergraduates. I hope it finds some use.

Branch on Clinton.

“‘I’m not calling this a biography of Clinton or a history of the administration,’ Mr. Branch said in a telephone interview from Baltimore, where he lives. ‘It is what it was like to live through it that way, sitting alone with him, talking about the presidency as he saw it, right in the moment.‘” Pulitzer-Prize winning King historian Taylor Branch announces a forthcoming book based on intimate conversations with Bill Clinton over the course of his presidency. “David Rosenthal, the publisher of Simon & Schuster, said the material ‘is wide-ranging, largely unguarded and gives tremendous insight into the thought processes and real-time concerns of a sitting president.’“

Echoes of Aguinaldo?

“It was a war that the United States had not planned, and did not expect, to fight. It was a war in which the superiority of American civilization was supposed to bring grace to a foreign people. It was a war that the United States seemed to win quickly and with ease, but that somehow did not end.” Over at Slate, historian David Silbey ponders what the Phillippine War of 1899-1902 tells us about Iraq. Silbey’s emphasis on political counterinsurgency seems sound, but, given that the Philippines wasn’t on the verge of a sectarian civil war at the time, I’m not sure his strategy for victory plays out in Baghdad, particularly at this late date.

The (Possibly) Good German.

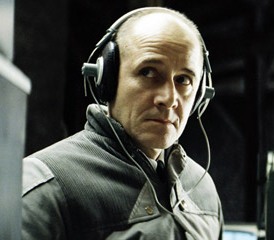

In David Fincher’s Zodiac, well-intentioned cops from different jurisdictions conduct archival sleuthing and the occasional phone trace to track down a cold-blooded killer. But, in Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s powerful, humanistic The Lives of Others, the second half of my double-feature last Friday, the bureaucratic machinery of the State grinds into gear for a darker purpose. Here, in the final flower of Erich Honecker’s East Germany, the Stasi keep their eyes and ears on those who would threaten the integrity of the German Democratic Republic, which, sadly, counts as just about everyone. I know very little about this subject, so I can’t vouch for how well van Donnersmarck recreates the rigors of East German life in the 1980s. Still, as an Orwellian parable of secrets and surveillance, The Lives of Others is a very worthwhile film, one strong enough to overcome some perhaps overly cliched moments of awakening by various characters along the way.

In David Fincher’s Zodiac, well-intentioned cops from different jurisdictions conduct archival sleuthing and the occasional phone trace to track down a cold-blooded killer. But, in Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s powerful, humanistic The Lives of Others, the second half of my double-feature last Friday, the bureaucratic machinery of the State grinds into gear for a darker purpose. Here, in the final flower of Erich Honecker’s East Germany, the Stasi keep their eyes and ears on those who would threaten the integrity of the German Democratic Republic, which, sadly, counts as just about everyone. I know very little about this subject, so I can’t vouch for how well van Donnersmarck recreates the rigors of East German life in the 1980s. Still, as an Orwellian parable of secrets and surveillance, The Lives of Others is a very worthwhile film, one strong enough to overcome some perhaps overly cliched moments of awakening by various characters along the way.

When we first meet Capt. Gerd Wiesler (Ulrich Muhe), with his sleek dome, thin ties, and retrofuturistic jacket, he’s training young Stasi cadets in the subtler techniques of interrogation and threatening landladies with the ruin of their children’s future — clearly a right rotten bastard of the first order. Still, there’s something undeniably impressive about the ever watchful Wiesler, a man who’s both cognizant of even the slightest emotional shifts in his prey and committed fully to the ideological aspirations of the Party. Wiesler’s skill and fervor is not lost on party flunky Anton Grubitz (Ulrich Tukur), who assigns him to a career-making case of digging up dirt on the roguishly handsome, go-along-to-get-along playwright Georg Dreyman (Sebastian Koch) for a well-connected romantic rival.

But, something — perhaps the sight of Dreyman’s beautiful actress girlfriend Christa-Maria Sieland (Martina Gedeck) on stage, perhaps something else — clicks in Wiesler as he conducts his round-the-clock surveillance. And, from the dismal attic above Dreyman’s apartment, Capt. Wiesler soon begins, despite himself, to commit Thoughtcrime. And as Dreyman begins to associate with known subversives and the investigatory noose tightens, Wiesler finds himself increasingly complicit in the machinations of the artists downstairs, so much so that he soon, if he’s not very, very careful, runs the risk of being the Stasi’s next target.

I can see the criticism that The Lives of Others can occasionally be a bit too pat. The distinctions between Wiesler and Dreyman are perhaps a bit overdrawn (Dreyman’s apartment is always suffused with a warm glow, and he and Sieland are invariably surrounded by friends, music, and the finer things in life; meanwhile, Wiesler scurries about the cold, gray machines upstairs, and basically lives like Eleanor Rigby — get a dog, Captain), and there are definitely a few cliche-ridden scenes along the way (for example, one involving the instantly transformative power of Beethoven — you’ll know what i mean.

Still, The Lives of Others is affecting in the details: Dreyman (“Lazlo”) and Sieland (“CMS”) are reduced to abstractions by the Stasi’s surveillance regime, with all the messy, conflicted, and emotion-ridden qualities that make them human drained away. (“They presumably have intercourse,” comments Wiesler dryly in his report after one tender moment.) Conversely, Wiesler’s attempts to break free of his own self-imposed leash and sound even the feeblest of barbaric yawps are moving in their own way, be it his sneaking out a dog-eared copy of Brecht from Dreyman’s shelf or renegotiating his interrogation strategy on an eight-year-old in his elevator.

Still, The Lives of Others is affecting in the details: Dreyman (“Lazlo”) and Sieland (“CMS”) are reduced to abstractions by the Stasi’s surveillance regime, with all the messy, conflicted, and emotion-ridden qualities that make them human drained away. (“They presumably have intercourse,” comments Wiesler dryly in his report after one tender moment.) Conversely, Wiesler’s attempts to break free of his own self-imposed leash and sound even the feeblest of barbaric yawps are moving in their own way, be it his sneaking out a dog-eared copy of Brecht from Dreyman’s shelf or renegotiating his interrogation strategy on an eight-year-old in his elevator.

The Lives of Others ends with a coda that at first seems too long but ultimately sounds just the right note: As Auden memorably put it, There is no such thing as the State, and no one exists alone; Hunger allows no choice to the citizen or the police; We must love one another or die. May I, composed like them of Eros and of dust, beleaguered by the same negation and despair, show an affirming flame.

Sign of the Beast.

More a straightforward police procedural than the type of visually kinetic extravaganza one might expect from the director of Se7en and Fight Club, David Fincher’s Zodiac, which I saw on Friday, is a slow-moving but generally effective film. I confess to having very little interest in the story of the Zodiac killer, or in serial killer movies in general. Still, I found Zodiac to be a somber and engaging character study of the cops, journalists, and suspects caught up in the hunt for San Francisco’s most famous murderer, and a moody meditation on how, as months yield to years without a definitive answer, the long, tiring search for truth comes to haunt and drain their lives away. It may basically play like a seventies throwback Law and Order for most of its run, with occasional flourishes from The Wire, but Zodiac is still a worthwhile film, and one that marks a welcome rebound for Fincher after the relatively uninspired Panic Room. It’s good to see his sign rising once again.

More a straightforward police procedural than the type of visually kinetic extravaganza one might expect from the director of Se7en and Fight Club, David Fincher’s Zodiac, which I saw on Friday, is a slow-moving but generally effective film. I confess to having very little interest in the story of the Zodiac killer, or in serial killer movies in general. Still, I found Zodiac to be a somber and engaging character study of the cops, journalists, and suspects caught up in the hunt for San Francisco’s most famous murderer, and a moody meditation on how, as months yield to years without a definitive answer, the long, tiring search for truth comes to haunt and drain their lives away. It may basically play like a seventies throwback Law and Order for most of its run, with occasional flourishes from The Wire, but Zodiac is still a worthwhile film, and one that marks a welcome rebound for Fincher after the relatively uninspired Panic Room. It’s good to see his sign rising once again.

After the first of many impressive establishing shots of San Francisco, set to some spooky post-psychedelic pop ditty of the era, Zodiac begins on July 4th, 1969, with what feels like both a classic urban legend and a recipe for disaster — two young people flirting and fumbling at a dark and abandoned Lover’s Lane. Only this story is true, and soon enough, the Zodiac has struck for the second time, leaving one dead and another terribly wounded in his wake. Showing a penchant for publicity that will make him a household name in the Bay Area over the next few years, the Zodiac sends both boastful and encoded message to several major newspapers. These pique the interest of — among others — a hard-drinking, hard-living writer on the cop beat (Robert Downey, Jr.), a nebbishy cartoonist with a knack for puzzles (Jake Gyllenhaal, playing the author of the book on which the film is based), and two peace officers (Mark Ruffalo, Anthony Edwards) assigned to track down this preening sociopath before he strikes again. For the next few years, we follow each of these fellows as they attempt to pin down the identity of the elusive killer: negotiating bureaucratic snafus, parsing encrypted texts, and, yes, hitting the archives like good, little researchers. But the trail of the Zodiac exacts a heavy toll, and as the Age of Aquarius fades into the Reagan era, each of these men leave the decade scarred by their quest, some irreparably. And still, somewhere out there, the Zodiac lurks…

After the first of many impressive establishing shots of San Francisco, set to some spooky post-psychedelic pop ditty of the era, Zodiac begins on July 4th, 1969, with what feels like both a classic urban legend and a recipe for disaster — two young people flirting and fumbling at a dark and abandoned Lover’s Lane. Only this story is true, and soon enough, the Zodiac has struck for the second time, leaving one dead and another terribly wounded in his wake. Showing a penchant for publicity that will make him a household name in the Bay Area over the next few years, the Zodiac sends both boastful and encoded message to several major newspapers. These pique the interest of — among others — a hard-drinking, hard-living writer on the cop beat (Robert Downey, Jr.), a nebbishy cartoonist with a knack for puzzles (Jake Gyllenhaal, playing the author of the book on which the film is based), and two peace officers (Mark Ruffalo, Anthony Edwards) assigned to track down this preening sociopath before he strikes again. For the next few years, we follow each of these fellows as they attempt to pin down the identity of the elusive killer: negotiating bureaucratic snafus, parsing encrypted texts, and, yes, hitting the archives like good, little researchers. But the trail of the Zodiac exacts a heavy toll, and as the Age of Aquarius fades into the Reagan era, each of these men leave the decade scarred by their quest, some irreparably. And still, somewhere out there, the Zodiac lurks…

Its opening moments notwithstanding, most of Zodiac is concerned not with nasty serial killer exploits (although there are a few, such as a jarring afternoon picnic at the lake) but the ugly mechanics of the cops and journalists’ search, with all its circumstantial theorizing and bureaucratic gear-grinding. Some of this stuff, such as the memory-holes that arise between overlapping jurisdictions of various Bay Area law enforcement bureaus, would probably seem fresher if you’ve never watched The Wire, where police mismanagement and careerism is a central staple. (That being said, likable character actors like Elias Koteas, Donal Logue, and Zach Grenier spice up these scenes considerably.) But, other facets of the hunt still resonate, such as how multiple explanations pile up for a given clue with no real way to determine the correct one. The Zodiac’s symbol…is it a cross-hair, or was it stolen from a watch company, or is it the countdown from the opening of a film reel? Each answer seems like it must be the definitive one at different times, and, for the participants in this haunted search, the shifting interpretations grow increasingly maddening. The film is kind enough to give the audience something of a sense of closure at the end, but Zodiac is most intriguing when it leaves all doors open, and lets its characters get thrown about in the bruising wind that ensues.

Its opening moments notwithstanding, most of Zodiac is concerned not with nasty serial killer exploits (although there are a few, such as a jarring afternoon picnic at the lake) but the ugly mechanics of the cops and journalists’ search, with all its circumstantial theorizing and bureaucratic gear-grinding. Some of this stuff, such as the memory-holes that arise between overlapping jurisdictions of various Bay Area law enforcement bureaus, would probably seem fresher if you’ve never watched The Wire, where police mismanagement and careerism is a central staple. (That being said, likable character actors like Elias Koteas, Donal Logue, and Zach Grenier spice up these scenes considerably.) But, other facets of the hunt still resonate, such as how multiple explanations pile up for a given clue with no real way to determine the correct one. The Zodiac’s symbol…is it a cross-hair, or was it stolen from a watch company, or is it the countdown from the opening of a film reel? Each answer seems like it must be the definitive one at different times, and, for the participants in this haunted search, the shifting interpretations grow increasingly maddening. The film is kind enough to give the audience something of a sense of closure at the end, but Zodiac is most intriguing when it leaves all doors open, and lets its characters get thrown about in the bruising wind that ensues.

Roll, Jordan, Roll.

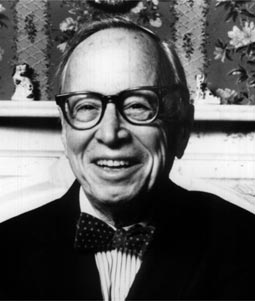

Schlesinger isn’t the only noted historian we’ve lost of late. A belated farewell to Winthrop Jordan, 1931-2007. (Via Cliopatria.)

The Age of Schlesinger.

“History is a doomed enterprise that we happily pursue because of the thrill of the hunt, because exploring the past is such fun, because of the intellectual challenges involved, because a nation needs to know its own history. Or so we historians insist. Because in the end, a nation’s history must be both the guide and the domain not so much of its historians as its citizens.” Arthur Schlesinger Jr., 1917-2007. After Galbraith passed on last year, this seemed like it would soon be in the cards. Still, it’s a sad day. Update: Via Ted, David Greenberg weighs in on Schlesinger’s passing.