Dad to Daleks, Mom to Muppets, Uncle to Many.

Haunting the Web Since 1999

Who is this old man, and how his fate bound up with Hugo’s? That is the question that drives this historical fairy tale (formerly Brian Selznick’s The Invention of Hugo Cabret.) What follows is a child’s adventure story, a fantastic and whimsical tale of movie history bound up in the love of film itself, and an exercise in 3D innovation forged by a master craftsman with clockwork precision and…ok, let’s take a breath here. At the risk of opening myself to charges of pearls before swine, can I actually just confess to being a little bored by Hugo?

Mind you, I’m not happy about it: I love movies, i like historical fantasy. By the syllogistic principle, I should adore a historical fable about loving movies. In addition Hugo is an exceedingly well-made entertainment, and I presume it works reasonably well as a family film for Potter-inclined children of a certain age and temperament. (Although, frankly, I could imagine a lot of kids being bored too.) And every time some new character popped into the story, it was almost always an actor or actress — Chloe Moretz, Ray Winstone, Michael Stuhlbarg — that I’m fond of watching. But it’s a plain fact that, however entrancing Scorsese’s second- and third-act invocations of Georges Melies — the cinema’s first imagineer, as it were — I watched Hugo feeling mostly disengaged from it.

In the interests of full disclosure, while thinking over the reasons for how this clinical distance might’ve happened, it occurred to me after the fact that I have felt much the same about almost every other one of Martin Scorsese’s films. I’m not saying the man’s a hack or anything — He’s clearly an exceptional craftsman and a deservedly historic figure among American directors. But from his early classics (Mean Streets, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, all of which I saw on VCR years after they came out) to Goodfellas (which, to be fair, I caught after The Sopranos) to his recent run of films (Gangs of New York, The Aviator, Shutter Island, The Departed), I’ve had almost the same reaction in the end to every one of his films: Well that was well-put-together, but not very emotionally engaging. (The one major exception here, and my favorite Scorsese movie, is The Last Temptation of Christ, although I also quite like Casino and The King of Comedy. Update: And Kundun, After Hours, and The Age of Innocence as well, now that I think more on it.)

The other issue at work here is the issue of the Third Dimension. Over the course of its run, Hugo — a movie which eventually discusses the earliest days of the cinema — not very subtly makes a case that we are witnessing a similar birth of a new art form right now, with 3D technology. (After showing us the Lumiere brothers’ 1895 film of an arriving train, which scared audiences untrained in film-watching into thinking they’d be run over, Scorsese recreates the scene at the Gare Montparnasse using 2011’s finest 3D tech.) Now, I know that saying things like “3D movies are just a fad” is exactly the type of statement that will leave one ripe for ridicule down the road. (re: “Talkies will never catch on,” or “Why would we ever need color?“) Buuuuut…I’m still not entirely sure the current 3D boom is anything more than a fad.

Here’s the thing: I’m glad visionary directors like Scorsese, James Cameron, and Peter Jackson are pushing the envelope and the technology on 3D. (For what it’s worth, Cameron says Hugo is the best 3D photography he’s ever seen. I’ll reserve full judgment until I’ve seen The Hobbit at 48 frames per second.) At the same time, it seems to me that, at least at present, 3D is mainly being used as a way to push audiences to continue seeing films on the big screen instead of watching them at home. In other words, it’s a filler technology being used to paper over the gaps at a transitional time for the medium, and its recent embrace has more to do with the business of movies than the art of them.

So, my skepticism about 3D at the moment isn’t really about being a Luddite. If anything, the technology isn’t advanced enough yet. When audiences can see the effect without wearing the damnable headache-inducing glasses, or we move past screen projection to full three-dimensional projection, not unlike the holograms in Star Wars, then I might start to agree we’re in Lumiere or Melies territory. But making movies look vaguely and unnecessarily like pop-up books, or having a ginormous Sasha Baron Cohen head jump out at you rather than the usual arrows and projectiles or whatnot, is not really a game-changing use of the medium, and it seems a bit hubristic to suggest so.

I still submit that the most groundbreaking use of 3D I’ve ever witnessed was in the concert film U2 3D, which layered completely separate images into one field of vision, and thus suggested an entirely new form of cinema syntax. Unfortunately, neither Cameron nor Scorsese have opted to explore that route as of yet. Instead, Scorsese has given us here a fine example of how standard story-telling can be slightly enhanced by 3D. I just wish it wasn’t so ponderous at times. Your mileage may vary, of course, but when I was having reactions during the movie like, “Oh Lord, we’re about to get another ten minutes of Sasha Baron Cohen playing the martinet,” that is just not a good sign.

In the trailer bin of late (along with the Bat, the Spider, and the Forelock):

As iconic cuts by New Order and The Smiths tip off in the opening moments, The History Boys takes place in the early 1980’s — 1983 Sheffield, to be exact. But don’t let “Blue Monday” and “This Charming Man” fool you: our story in fact takes place in a boys’ preparatory school, one — references to W.H. Auden and Brief Encounter notwithstanding — seemingly hermetically sealed from the outside world at large. Here in this academic biodome, several young lads, having done exceedingly well on their A-levels, now prep for the grueling college application process, in the particular hopes of getting into Oxford and Cambridge.

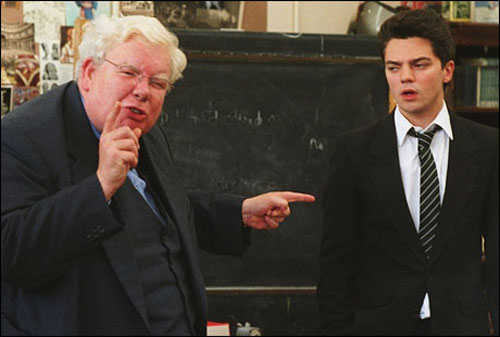

To aid them in this arduous process are two history professors dueling for their impressionable minds…and bodies: In the relativist corner, Professor Irwin (Stephen Campbell Moore), a sharp, young, and assured (if closeted) new hiree dedicated to promoting the ironies and contingencies of history. Meanwhile, over in the knowledge-for-its-own-sake department rests Professor Hector (Richard Griffiths, the soul of the film.) Orwell looming over his shoulder (the two agree on the debasement of “worrrrds“), Hector is a grotesque but endearing fellow who one might call avuncular, were it not for his rather unfortunate penchant for fondling his students’ genitals. Shrugging off these occasional gropes (far more sanguinely than seems realistic, IMHO), the history boys perform poetry, film scenes, and cabaret tunes for the latter and develop streaks of contrarian skepticism for the former, all the while learning a thing or two not only about life and history, but of the Achilles’ Heels of their esteemed teachers.

In a nutshell, the basic problem I had with The History Boys is this: A decade ago, a friend of mine once described a mutual acquaintance as “the ideal twenty-two-year-old…in the eyes of a fifty-five-year old.” Well, this movie’s got a whole pack of ’em. All of the young actors here are decent enough — if a bit broad, cinematically speaking — with Samuel Barnett (as Posner, a boy trapped in the very special hell that is an unrequited teenage crush) and Dominic Cooper (as Dakin, a young man increasingly hopped up on Nietzsche and the power of his own burgeoning sexuality) given the most to do. But, as they effortlessly spin forth witticisms at the most opportune moments and gather around the piano without even a trace of cynicism or irony (“the shackles of youth,” as the line goes) about them, they all seemed very, very improbable to me…and that’s even notwithstanding their handling of the aforementioned sexual misdeeds. (Full disclosure: I have much the same problem with Whit Stillman films.)

Yet, once you take it as inherently fanciful and somewhat missuited for the big screen, there are still elements to enjoy in Boys, including a number of thoughtful disquisitions on the uses and practices of history as a discipline: for example, on contingency, commemoration, and the rise of a more gender-balanced understanding of the past (the latter memorably delivered by Frances De La Tour, who, while excellent here as a jaded prof, still unfortunately kept reminding me of Madame Maxime.) Admittedly, these digressions do seem shoehorned in at times — and brought back memories of fading historiography seminars — but they still offer some keen grist for the philosophical mill. (That being said, I somehow suspect that the teaching of history is a less sexually charged discipline than as seen here, where it’s rife with more suppressed longing than the Catholic priesthood. But perhaps I haven’t been at it long enough.)

The trailer for Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is now online. Alfonso Cuaron, Gary Oldman, David Thewlis, Tim Spall…this has to be better than the first two, right?