“

A song will lift, as the mainsail shifts, and the boat drifts on to the shoreline.” If you’ve been reading this site for any length of time, you probably already know that I

drank the Bob Dylan kool-aid a good while ago. So, more than likely, my opinion of

Todd Haynes’ I’m Not There, which I raced down (

on the D-train, no less) to catch at the

Film Forum this morning, should be taken with at least a shaker of salt. And, to be honest, it’s hard to imagine how this film plays to people who aren’t all that into Dylan — If you don’t already have a basic sense of his story and his various periods, I could see it being as incoherent and irritating as

Southland Tales (although it’s assuredly better-made.) But, if you do have any fondness for Bob, oh my. The short review is: I

loved it. Exploding the conventional music biopic into shimmering, impressionistic fragments, Todd Haynes has captured lightning in a bottle here. The movie is clearly a labor of love by and for Dylan fans, riddled with in-jokes, winks, and nods, and I found it thoughtful, funny, touching, and wonderful. Put simply, while

No Country for Old Men is right up there,

I’m Not There is my favorite film of the year. I can’t wait to see it again.

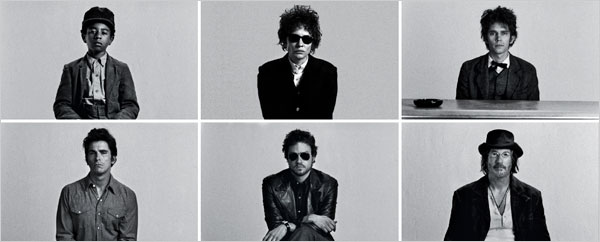

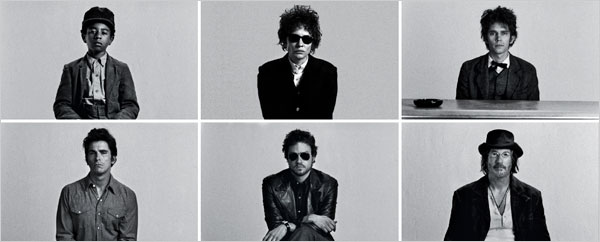

Like Navin Johnson, Bob Dylan was born a poor black child. (Marcus Carl Franklin) Ok, perhaps not. But Hayne’s movie doesn’t really aim to tell the story of one Robert Zimmerman of Hibbing, Minnesota. anyway. — He’s not there. Instead I’m Not There refracts Dylan through a prism of sorts, giving us multiple versions of the man (and myth) at various stages in his life and work. And, so, after a first person POV shot of “Dylan” (us?) taking the stage in ’66, and a title shot involving a potentially-momentous motorcycle, we are introduced to one Woody Guthrie (Franklin), an 11-year-old folk wunderkind traveling hobo-style along the rails, singing union songs and making up his past as he goes along. But the times they-are-a-changin’, and, as a kindly matron informs Woody, the old songs don’t necessarily do justice to the problems of 1959. Enter Jack Rollins (Christian Bale), an earnest young troubador who once lit Greenwich Village on fire with his ballads of social protest (“finger-pointin’ songs”), and, having rejected the folk scene and found Jesus, is now the subject of a No Direction Home-style documentary. (Julianne Moore does a Joan Baez impression here, straight out of Scorsese’s doc, which is pretty hilarious, and maybe even a little mean — note the business with the cat.)

Like Navin Johnson, Bob Dylan was born a poor black child. (Marcus Carl Franklin) Ok, perhaps not. But Hayne’s movie doesn’t really aim to tell the story of one Robert Zimmerman of Hibbing, Minnesota. anyway. — He’s not there. Instead I’m Not There refracts Dylan through a prism of sorts, giving us multiple versions of the man (and myth) at various stages in his life and work. And, so, after a first person POV shot of “Dylan” (us?) taking the stage in ’66, and a title shot involving a potentially-momentous motorcycle, we are introduced to one Woody Guthrie (Franklin), an 11-year-old folk wunderkind traveling hobo-style along the rails, singing union songs and making up his past as he goes along. But the times they-are-a-changin’, and, as a kindly matron informs Woody, the old songs don’t necessarily do justice to the problems of 1959. Enter Jack Rollins (Christian Bale), an earnest young troubador who once lit Greenwich Village on fire with his ballads of social protest (“finger-pointin’ songs”), and, having rejected the folk scene and found Jesus, is now the subject of a No Direction Home-style documentary. (Julianne Moore does a Joan Baez impression here, straight out of Scorsese’s doc, which is pretty hilarious, and maybe even a little mean — note the business with the cat.)

By now, you probably see where this is going. Post-Newport, Cate Blanchett shows up as Jude, a.k.a. the reedy, combative, drugged-out, and dog-tired Dylan of (blonde on) Blonde on Blonde and Don’t Look Back. (It takes a woman like her, to get through, to the man in him.) Ben Whishaw shares the load of society’s probing as Arthur Rimbaud, a Bob who spends most of the movie facing down some unknown interlocutors. Heath Ledger’s Robbie is the romantic and the womanizer, the Dylan who woos the heartbreakingly beautiful Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg, playing an amalgamation of Suze Rotolo and Sara Lownds), looks for solace in a normal life outside Woodstock, and eventually stares into the abyss of Blood on the Tracks. And Richard Gere is Billy, an aging outlaw hiding out in Riddle, MO, part of the mythical American landscape conjured by Bob in “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” “Desolation Row,” John Wesley Harding, The Basement Tapes, “Blind Willie McTell,” and countless other songs.

By now, you probably see where this is going. Post-Newport, Cate Blanchett shows up as Jude, a.k.a. the reedy, combative, drugged-out, and dog-tired Dylan of (blonde on) Blonde on Blonde and Don’t Look Back. (It takes a woman like her, to get through, to the man in him.) Ben Whishaw shares the load of society’s probing as Arthur Rimbaud, a Bob who spends most of the movie facing down some unknown interlocutors. Heath Ledger’s Robbie is the romantic and the womanizer, the Dylan who woos the heartbreakingly beautiful Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg, playing an amalgamation of Suze Rotolo and Sara Lownds), looks for solace in a normal life outside Woodstock, and eventually stares into the abyss of Blood on the Tracks. And Richard Gere is Billy, an aging outlaw hiding out in Riddle, MO, part of the mythical American landscape conjured by Bob in “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” “Desolation Row,” John Wesley Harding, The Basement Tapes, “Blind Willie McTell,” and countless other songs.

Each of this fellowship of Dylans does quality work in the role. Cate Blanchett is getting the most press these days, perhaps deservedly so, but I was as impressed with Bale, Whishaw, Franklin, and particularly Ledger — After seeing the extent of his range here, it’s pretty clear he’s going to kill as the Joker next summer. And other actors resonate here as well. I already mentioned Julianne Moore and the exquisite Charlotte Gainsbourg. (My crush on the latter, already simmering after The Science of Sleep, will no doubt grow by leaps and bounds now, particularly once you factor in her fragile, breathy version of “Just Like a Woman” on the soundtrack. With a face that’s at once honest, open, statuesque, and melancholy, she’s the perfect sad-eyed lady of the lowlands.) Also notable is David Cross, the spitting image of Allen Ginsberg, Michelle Williams invoking Factory Girl Edie Sedgwick, and a well-preserved Richie Havens delivering a Joe Cocker moment with his version of “Tombstone Blues.” Bruce Greenwood (of Thirteen Days, The Sweet Hereafter, and recently John from Cincinnati) does particularly impressive work as Jude’s nemesis, a BBC newsman who wants to pin both the mercurial singer and the meaning of his (her) music to the wall like a butterfly. Clearly, something is happening here, but he don’t know what it is…

Each of this fellowship of Dylans does quality work in the role. Cate Blanchett is getting the most press these days, perhaps deservedly so, but I was as impressed with Bale, Whishaw, Franklin, and particularly Ledger — After seeing the extent of his range here, it’s pretty clear he’s going to kill as the Joker next summer. And other actors resonate here as well. I already mentioned Julianne Moore and the exquisite Charlotte Gainsbourg. (My crush on the latter, already simmering after The Science of Sleep, will no doubt grow by leaps and bounds now, particularly once you factor in her fragile, breathy version of “Just Like a Woman” on the soundtrack. With a face that’s at once honest, open, statuesque, and melancholy, she’s the perfect sad-eyed lady of the lowlands.) Also notable is David Cross, the spitting image of Allen Ginsberg, Michelle Williams invoking Factory Girl Edie Sedgwick, and a well-preserved Richie Havens delivering a Joe Cocker moment with his version of “Tombstone Blues.” Bruce Greenwood (of Thirteen Days, The Sweet Hereafter, and recently John from Cincinnati) does particularly impressive work as Jude’s nemesis, a BBC newsman who wants to pin both the mercurial singer and the meaning of his (her) music to the wall like a butterfly. Clearly, something is happening here, but he don’t know what it is…

Do you need to know a lot about Dylan going in? Well, it undoubtedly helps. I’m Not There is rife throughout with Dylanalia, and, yes, at times it’s dropped as blatantly as the groaners in Across the Universe: Jude mutters “Just like a woman!” at one point as a punchline, and an LBJ on the wall during a party strangely exclaims “It’s not yellow, it’s chicken.” But, others are more obscure, hidden in the fabric of the film like a crossword puzzle for Dylanophiles. Many of the strange denizens of Gere’s Riddle recall characters in songs or various Dylan incarnations, from the whitefaced troubador at Ms. Henry‘s funeral to the Union solders and passing Lincoln on stilts. As Robbie and Claire (Renaldo and Clara?) have one of those tired, terse phone discussions that signifies the end is near, a movie poster over her shoulder reads “CALICO” (i.e. “Sara,” the “calico sphinx in a scorpio dress (you must forgive me my unworthiness.)“) Or, in the scene accompanying one of Dylan’s masterpieces, “Visions of Johanna,” the Ledger Dylan, a movie star of sorts, is bored on the road and skirt-chasing one of his co-stars. As this goes down, we happen to see some elderly crones in neck braces (“the jelly-faced women all sneeze“), Ledger walking in a museum (“Inside the museum, Infinity goes up on trial“), the Mona Lisa (who “musta had the highway blues, you can tell by the way she smiles“), and the co-star he’s tailing, of course, is named Louise. (“Louise, she’s all right, she’s just near. She’s delicate and seems like the mirror. But she just makes it all too concise and too clear that Johanna’s not here.“)

Do you need to know a lot about Dylan going in? Well, it undoubtedly helps. I’m Not There is rife throughout with Dylanalia, and, yes, at times it’s dropped as blatantly as the groaners in Across the Universe: Jude mutters “Just like a woman!” at one point as a punchline, and an LBJ on the wall during a party strangely exclaims “It’s not yellow, it’s chicken.” But, others are more obscure, hidden in the fabric of the film like a crossword puzzle for Dylanophiles. Many of the strange denizens of Gere’s Riddle recall characters in songs or various Dylan incarnations, from the whitefaced troubador at Ms. Henry‘s funeral to the Union solders and passing Lincoln on stilts. As Robbie and Claire (Renaldo and Clara?) have one of those tired, terse phone discussions that signifies the end is near, a movie poster over her shoulder reads “CALICO” (i.e. “Sara,” the “calico sphinx in a scorpio dress (you must forgive me my unworthiness.)“) Or, in the scene accompanying one of Dylan’s masterpieces, “Visions of Johanna,” the Ledger Dylan, a movie star of sorts, is bored on the road and skirt-chasing one of his co-stars. As this goes down, we happen to see some elderly crones in neck braces (“the jelly-faced women all sneeze“), Ledger walking in a museum (“Inside the museum, Infinity goes up on trial“), the Mona Lisa (who “musta had the highway blues, you can tell by the way she smiles“), and the co-star he’s tailing, of course, is named Louise. (“Louise, she’s all right, she’s just near. She’s delicate and seems like the mirror. But she just makes it all too concise and too clear that Johanna’s not here.“)

If this all is starting to sound like two and half hours of insufferable inside-baseball for Dylanheads, well, I guess it might be. But I really don’t think it plays like that. (And I also don’t think that was the appeal for me either. Both Masked and Anonymous and Twyla Tharp’s The Times They Are-A Changin’ trafficked in similar inside gags, and I didn’t enjoy those anywhere near as much as this film.) Basically, I’m Not There is too vibrant and enthusiastic to feel smug, remote, or exclusive about its fondness for Dylan. It never purports to define the meaning of any particular song, showing instead that more often than not their beauty lies in their ambiguity. (For example, both defenders of the cultural Old Guard and the Black Panthers feel “Ballad of a Thin Man” is about them.) And it often pokes fun at the Dylanophiles among us, throwing in a number of disgruntled fans at various times (particularly after Bob plugs in) and having Jude get pestered by an overeager amateur Dylanologist after hanging with the Beatles (a very jolly cameo indeed.) Plus, for all the reverence, Dylan himself isn’t as whitewashed as he was in No Direction Home — His drug habit, his youthful arrogance and occasional thin skin, and some questionable views on women poets are all on display here.

If this all is starting to sound like two and half hours of insufferable inside-baseball for Dylanheads, well, I guess it might be. But I really don’t think it plays like that. (And I also don’t think that was the appeal for me either. Both Masked and Anonymous and Twyla Tharp’s The Times They Are-A Changin’ trafficked in similar inside gags, and I didn’t enjoy those anywhere near as much as this film.) Basically, I’m Not There is too vibrant and enthusiastic to feel smug, remote, or exclusive about its fondness for Dylan. It never purports to define the meaning of any particular song, showing instead that more often than not their beauty lies in their ambiguity. (For example, both defenders of the cultural Old Guard and the Black Panthers feel “Ballad of a Thin Man” is about them.) And it often pokes fun at the Dylanophiles among us, throwing in a number of disgruntled fans at various times (particularly after Bob plugs in) and having Jude get pestered by an overeager amateur Dylanologist after hanging with the Beatles (a very jolly cameo indeed.) Plus, for all the reverence, Dylan himself isn’t as whitewashed as he was in No Direction Home — His drug habit, his youthful arrogance and occasional thin skin, and some questionable views on women poets are all on display here.

A talented artist in his own right (case in point: Safe and Far from Heaven), Haynes employs all the magic of the movies to tell Dylan’s story. The Robbie-and-Claire scenes are filmed in color occasionally as riotous as in Hayne’s homage to Douglas Sirk, Jack’s social protest and Christian periods are told in faux-documentary fashion, and Jude’s England tour is all black-and-white cinema verite, a la Don’t Look Back. That’s why I’m pretty sure i’m Not There will work even for people who don’t know the first thing about Dylan. It remains visually interesting throughout, and never falls into the usual biopic rut, that standard, hackneyed rise, fall, and rise again narrative which tends to bring down even otherwise well-made entrants in the genre like Walk the Line.

A talented artist in his own right (case in point: Safe and Far from Heaven), Haynes employs all the magic of the movies to tell Dylan’s story. The Robbie-and-Claire scenes are filmed in color occasionally as riotous as in Hayne’s homage to Douglas Sirk, Jack’s social protest and Christian periods are told in faux-documentary fashion, and Jude’s England tour is all black-and-white cinema verite, a la Don’t Look Back. That’s why I’m pretty sure i’m Not There will work even for people who don’t know the first thing about Dylan. It remains visually interesting throughout, and never falls into the usual biopic rut, that standard, hackneyed rise, fall, and rise again narrative which tends to bring down even otherwise well-made entrants in the genre like Walk the Line.

And, of course, it benefits from having one of the better soundtracks out there, and Haynes has expertly weaved Dylan’s music (and some quality cover versions) into almost every moment of the film. Let me put it this way: Within the first five minutes, I’m Not There features some period NYC subway footage set to the irrepressibly toe-tapping “Stuck Inside of Mobile With the Memphis Blues Again.” (Also another visual pun — the subway folk are “stuck inside of mobile.”) From that moment on, the movie pretty had much me. In the end, I don’t know if non-Dylan folk will vibe into it or not, but I found I’m Not There a splendid gift from one Dylan fan to the rest of us, and assuredly one of the more inventive and captivating biopics in recent filmdom. “And the sun will respect every face on the deck, the hour that the ship comes in.“