“If you are going to tell people the truth, you’d better make them laugh. Otherwise they’ll kill you.” This savvy George Bernard Shaw quote introduces Kevin Willmott’s razor-sharp documentary-satire C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America, which opened at the IFC Center tonight (followed by a Q&A), and, by that measure, Willmott’s film is a rousing success. At times both blisteringly funny and quietly devastating, C.S.A is a take-no-prisoners alternate history of our Confederacy — Yep, the South won — done in the style of Ken Burns’ The Civil War (or Andy Bobrow’s Old Negro Space Program), right down to bizarro versions of Shelby Foote and Barbara Fields. Punctuated throughout by offbeat television commercials that are eerily similar to today’s TV, C.S.A. is one of the best (and most ruthless and unflinching) satires I’ve seen in some time. And it illuminates a central fact often obscured in so many Brother-against-Brother tributes to America’s bloodiest conflict (as well as drek like Gods and Generals): The Civil War was begun and fought over slavery. In the words of C.S.A. Vice-President Alexander Stephens — in his inaugural address, no less — the Confederacy was founded “upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery –subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition.“

“If you are going to tell people the truth, you’d better make them laugh. Otherwise they’ll kill you.” This savvy George Bernard Shaw quote introduces Kevin Willmott’s razor-sharp documentary-satire C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America, which opened at the IFC Center tonight (followed by a Q&A), and, by that measure, Willmott’s film is a rousing success. At times both blisteringly funny and quietly devastating, C.S.A is a take-no-prisoners alternate history of our Confederacy — Yep, the South won — done in the style of Ken Burns’ The Civil War (or Andy Bobrow’s Old Negro Space Program), right down to bizarro versions of Shelby Foote and Barbara Fields. Punctuated throughout by offbeat television commercials that are eerily similar to today’s TV, C.S.A. is one of the best (and most ruthless and unflinching) satires I’ve seen in some time. And it illuminates a central fact often obscured in so many Brother-against-Brother tributes to America’s bloodiest conflict (as well as drek like Gods and Generals): The Civil War was begun and fought over slavery. In the words of C.S.A. Vice-President Alexander Stephens — in his inaugural address, no less — the Confederacy was founded “upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery –subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition.“

To kick off its conceit, C.S.A requires that you make two leaps of logic from the history of the Civil War: First, that, after the Emancipation Proclamation is issued, C.S.A. Secretary of State Judah P. Benjamin managed to convince England and France to join the war on the side of the Confederacy. (This was less likely, I think, than the film makes it out to be. Popular support in England — who had abolished slavery in 1833 — was pretty clearly on the side of the Union, particularly after Lincoln’s Proclamation, and “King Cotton diplomacy” just wasn’t going to work when England and France could import cotton instead from India, Egypt, and other waystations in their respective empires. And, even if the European powers had recognized the CSA, which they might’ve done had the South won more battles, they weren’t about to send troops across the Atlantic to fight on the side of slavery without severe popular repercussions.) Second, and more unlikely, is that, after capturing Washington DC, the South managed to subdue and annex the entire North, leveling Boston and Philadelphia (a la Sherman’s March) in the process. Even despite the Union’s hold on the Mississippi in the Western theater, the South might well have won the war, if Northern public opinion had collapsed in 1863 and 1864 (As it was, timely Union victories — and particularly the fall of Atlanta — buoyed Lincoln’s reelection.) But, had that happened, IMHO, there would likely be two nations uneasily living side by side for decades to come, as you find in Harry Turtledove’s How Few Remain series.

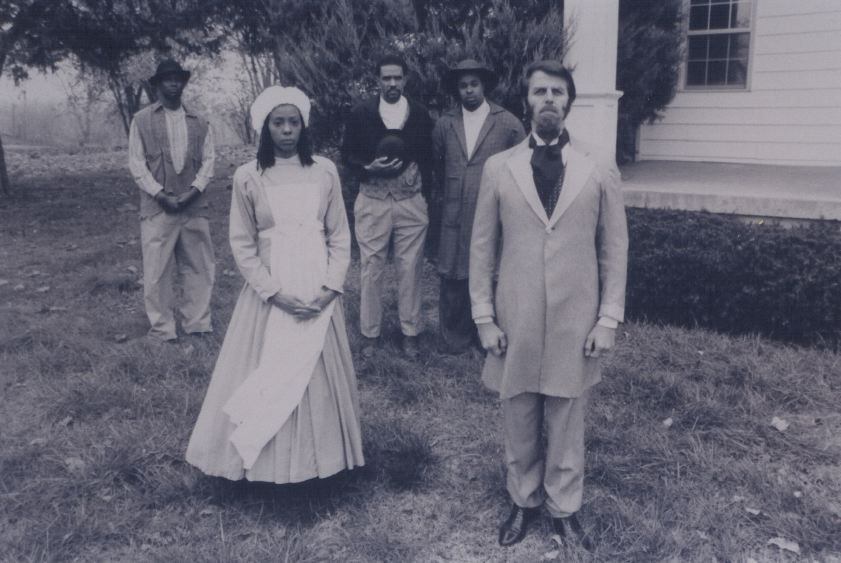

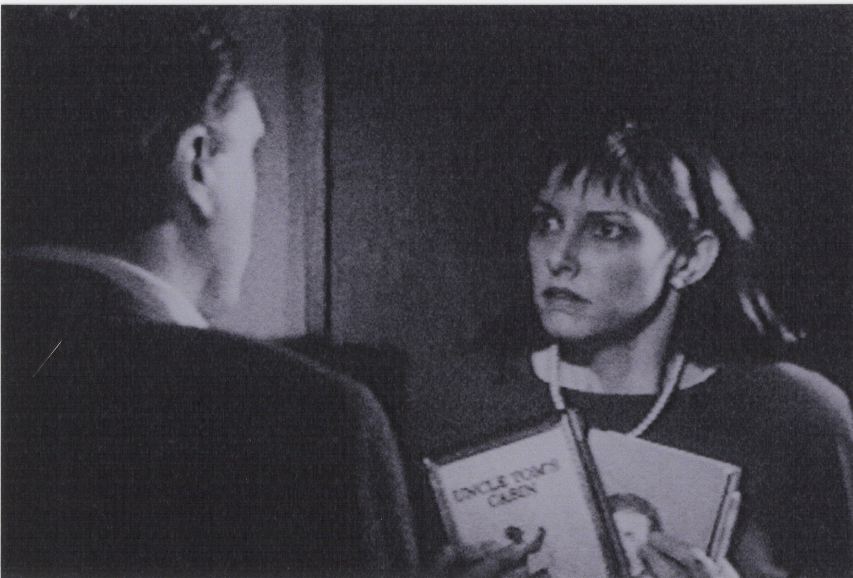

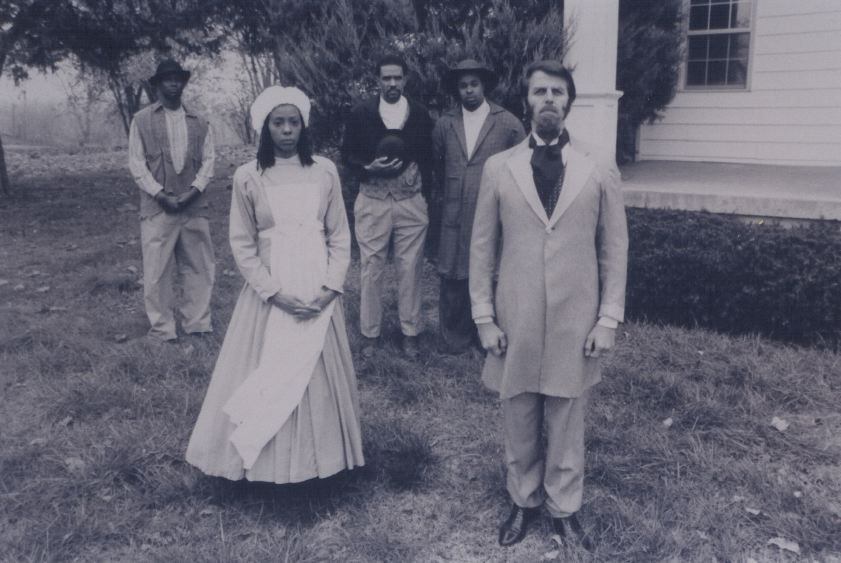

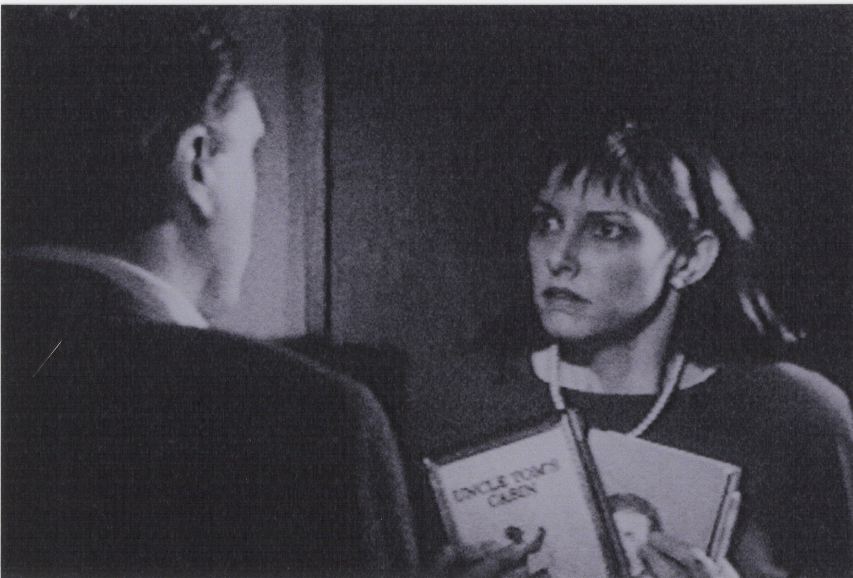

Ok, all that history geekery notwithstanding (which is somewhat unfair to the movie — it’s an alternate history satire, after all, which also explains the more recognizable battle flag replacing the official Stars and Bars on the moon and elsewhere), once you make the conceptual leap that the Confederacy managed to win the war and annex the Union, the rest of C.S.A is remarkably well-thought-out, and at times even scarily plausible. Like Jeff Davis, Lincoln is captured trying to escape in costume (on the Underground Railroad) and sent to Fort Monroe — Here, it’s dramatized in the 1915 D.W. Griffith film, The Hunt for Dishonest Abe. While the South contemplates various “Reconstruction” plans to reintroduce slavery to the North (and Nathan Bedford Forrest reenacts Fort Pillow over and over again), William Lloyd Garrison leads an abolitionist/transcendentalist contingent to Canada. Rather than the Chinese Exclusion Act, the C.S.A. passes a “Yellow Peril Mandate” providing for the enslaving of Chinese laborers. And, as in our world, the nation comes together again to fight a (here much broader) Spanish-American War.

As we get to the 20th century, C.S.A. continues to adroitly riff on American history. Audiences swarm to the Civil War musical, A Northern Wind. (“You tried to take my blacks, But I still want you back.“) In WWII, the C.S.A. plays nice with Germany while despising Japan. (Thanks to the service of Judah Benjamin, Jews can still live in the Confederacy, provided they stay on their “reservation” in Long Island.) Eventually, an armed, highly defended border — the “Cotton Curtain” — descends between Canada and the C.S.A., and ’50’s Confederates scour the nation for the “Abs” (abolitionists) in their midst. Later still, slave riots break out in Newark, Watts, and elsewhere in the turbulent ’60s, as many white Confederates reconsider slavery (due to global sanctions, give or take South Africa) and women begin to demand the vote.

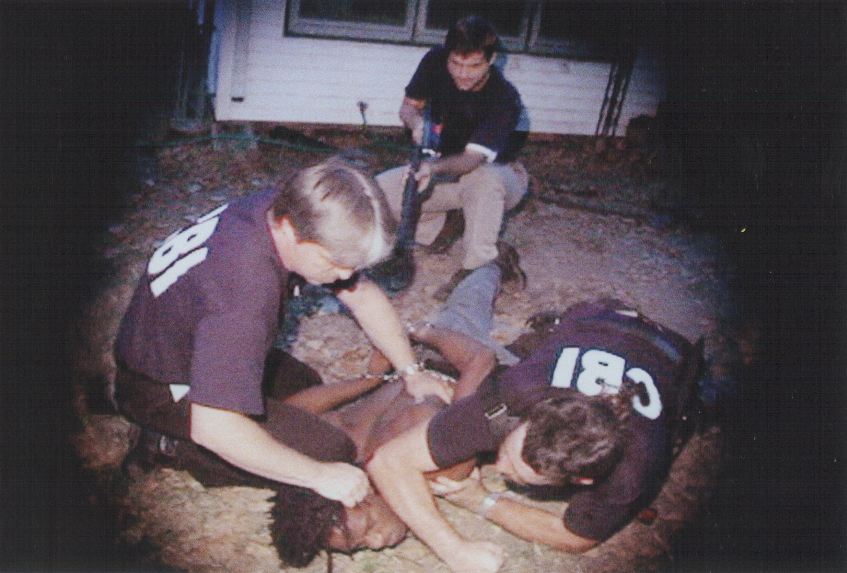

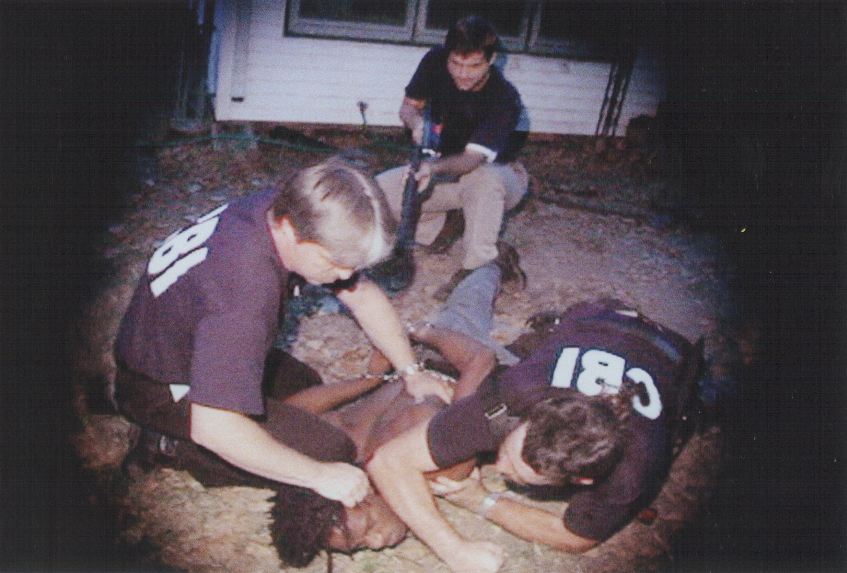

Equally as nimble as the mirror-image counterhistory of the CSA are the many commercial breaks throughout the fake documentary, with ads that are both jaw-droppingly brazen and laugh-out-loud funny. (You can get a sense of this from the trailer — Think Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, itself an excellent satire, to the nth degree.) They range from fake ads for unfortunately real products (Darky Toothpaste, Coon Chicken Inn) to all-too-possible modern innovations — The Slave Shopping Network, a LoJack “Shackle”, a Claritin-ish drug to treat drapetomania (the runaway disease “discovered” by Dr. Samuel Cartwright in 1851), a COPS-style show called RUNAWAYS, etc. etc. As you can see, this is withering stuff, and some might find it in horrible taste. But, there’s method to CSA’s madness. As I noted before, we tend to do a pitiful job of facing up to slavery, America’s Original Sin, and for ninety hilarious, cringeworthy minutes, CSA forces us to look the peculiar institution square in the eye. If we’re serious about our proclaimed role as a Beacon of Freedom to the world, that’s something we need to start doing a lot more often. (But, don’t worry — C.S.A. sweetens this tonic with quite a few laughs.) At any rate, if it’s anywhere near you, definitely go check it out.