I never caught the source material while it was on Broadway, so I can’t compare it to the play. But, while I found Nicholas Hytner’s film of Alan Bennett’s The History Boys to be a thoughtful and decently engaging piece of work, it makes for a somewhat unnatural and theatrical evening of cinema. The ideas in (the) play are obviously intriguing and worthy of contemplation, but — with several performances better suited for the back rows than the big screen (most notably Clive Merrison as a schoolmaster out of Monty Python) and a gaggle of bon mot-spouting teenagers that, at least in my own personal and teaching experience, act in no way at all like teenagers — The History Boys often felt forced to me. It’s a worthy piece of pedagogy, I suppose, and I’m almost positive it must work better on Broadway. But, overall, I thought it trafficked in archetypes more than it does in real-world, flesh-and-blood characters — more fiction than history, I’d say — and this close to the action, its faults are harder to hide.

As iconic cuts by New Order and The Smiths tip off in the opening moments, The History Boys takes place in the early 1980’s — 1983 Sheffield, to be exact. But don’t let “Blue Monday” and “This Charming Man” fool you: our story in fact takes place in a boys’ preparatory school, one — references to W.H. Auden and Brief Encounter notwithstanding — seemingly hermetically sealed from the outside world at large. Here in this academic biodome, several young lads, having done exceedingly well on their A-levels, now prep for the grueling college application process, in the particular hopes of getting into Oxford and Cambridge.

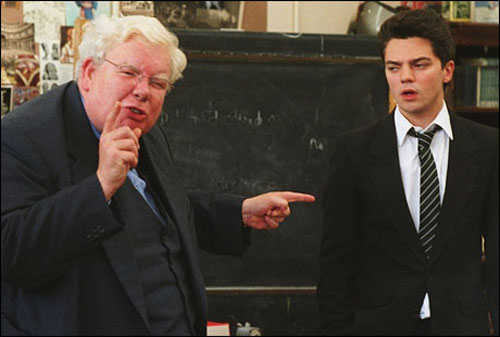

To aid them in this arduous process are two history professors dueling for their impressionable minds…and bodies: In the relativist corner, Professor Irwin (Stephen Campbell Moore), a sharp, young, and assured (if closeted) new hiree dedicated to promoting the ironies and contingencies of history. Meanwhile, over in the knowledge-for-its-own-sake department rests Professor Hector (Richard Griffiths, the soul of the film.) Orwell looming over his shoulder (the two agree on the debasement of “worrrrds“), Hector is a grotesque but endearing fellow who one might call avuncular, were it not for his rather unfortunate penchant for fondling his students’ genitals. Shrugging off these occasional gropes (far more sanguinely than seems realistic, IMHO), the history boys perform poetry, film scenes, and cabaret tunes for the latter and develop streaks of contrarian skepticism for the former, all the while learning a thing or two not only about life and history, but of the Achilles’ Heels of their esteemed teachers.

In a nutshell, the basic problem I had with The History Boys is this: A decade ago, a friend of mine once described a mutual acquaintance as “the ideal twenty-two-year-old…in the eyes of a fifty-five-year old.” Well, this movie’s got a whole pack of ’em. All of the young actors here are decent enough — if a bit broad, cinematically speaking — with Samuel Barnett (as Posner, a boy trapped in the very special hell that is an unrequited teenage crush) and Dominic Cooper (as Dakin, a young man increasingly hopped up on Nietzsche and the power of his own burgeoning sexuality) given the most to do. But, as they effortlessly spin forth witticisms at the most opportune moments and gather around the piano without even a trace of cynicism or irony (“the shackles of youth,” as the line goes) about them, they all seemed very, very improbable to me…and that’s even notwithstanding their handling of the aforementioned sexual misdeeds. (Full disclosure: I have much the same problem with Whit Stillman films.)

Yet, once you take it as inherently fanciful and somewhat missuited for the big screen, there are still elements to enjoy in Boys, including a number of thoughtful disquisitions on the uses and practices of history as a discipline: for example, on contingency, commemoration, and the rise of a more gender-balanced understanding of the past (the latter memorably delivered by Frances De La Tour, who, while excellent here as a jaded prof, still unfortunately kept reminding me of Madame Maxime.) Admittedly, these digressions do seem shoehorned in at times — and brought back memories of fading historiography seminars — but they still offer some keen grist for the philosophical mill. (That being said, I somehow suspect that the teaching of history is a less sexually charged discipline than as seen here, where it’s rife with more suppressed longing than the Catholic priesthood. But perhaps I haven’t been at it long enough.)