Everyone is evanescent, and everything in this world, no matter how beautiful or important, fades. Alas,

David Fincher’s striking but flawed The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is not exempt from this grim calculus. A lovely movie to gaze upon while it’s actually playing out,

Button begins to wither and deteriorate the minute you’re once again exposed to the sunlight.

To switch up metaphors, Button is a dazzling contraption at times, to be sure…but a contraption it remains. Unlike Milk, which felt alive in every moment of its run, the stately, strangely inert Button — despite trying to wring emotion from more death scenes than your average season of Six Feet Under — moves to a tidy, mechanical, and clockwork pulse that ultimately feels pretty far removed from the messy emotions and drawing-outside-the-lines sensations of real life. Fincher, the actors (particularly Brad Pitt, Cate Blanchett, and Taraji P. Henson), and the special effects team put forth an undeniably impressive effort, but as the movie progresses, it starts to feel more and more like what it in fact is: well-made but sloppily written Oscar bait. And the more you think about Button, the less it holds together.

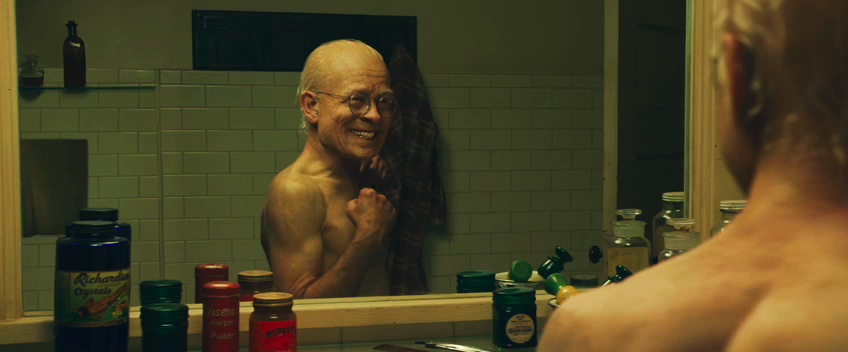

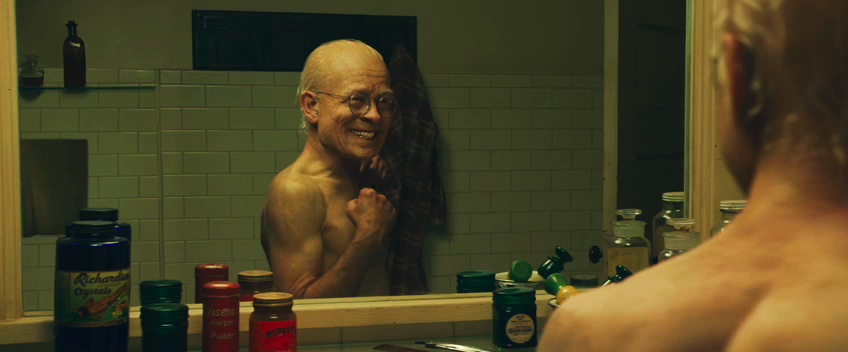

Trade out feathers for hummingbirds, and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button is, for all intent and purposes, Forrest Gump. (Indeed, while Button began as a Fitzgerald short story, the two films share a screenwriter in Eric Roth. It shows.) After a Katrina-era framing device is established, involving an old, terminally ill woman sharing her last few moments with her daughter (Julia Ormond) in a New Orleans hospital, we head back to 1918 and the end of World War I, as Benjamin Button begins to recount his tale…with a Gumpish southern drawl, no less. Born “under unusual circumstances” and left at the doorstep of the local old folks’ home, Button (Pitt, good but something of a cipher), as you probably know by now, ages backwards — He begins life as a very old baby and grows younger over time, like Dick Clark or the Bob Dylan song. (I’ve skipped over a short story involving Teddy Roosevelt and a distraught clockmaker (Elias Koteas) which, with the final visual payoff of the Katrina angle, may actually be the most beautiful and affecting part of the film.)

The central conceit established, Button’s life then proceeds to follow a surprisingly Gumpian course. Raised by his take-no-guff, God-fearin’ mama (Taraji P. Henson, a much-needed breath of life throughout) and considered a “special child” by all around him, Button eventually embarks on a series of grand adventures. He hooks up with a gruff but lovable sea captain (Jared Harris, nothing at all like Lt. Dan) who teaches him the ways of the world. He eventually finds himself in the midst of war, and spends several years traveling by himself all around the globe. And throughout his days, he finds himself continually drawn to his childhood friend turned free spirit, Jenny…uh, Daisy (Blanchett, graceful, alluring and thoroughly unDylanesque). But Daisy, like the rest of us, is aging along the usual lines. (Indeed, given that Daisy is a prima ballerina, her window of time seems that much shorter and more precious.) How can Benjamin and Daisy forge anything lasting when they’re at best two ships passing in the night? However happy they are at any given moment, time is against them and they know it. And time, whether one ages backwards or forwards, has a way of inexorably marching on.

There are scenes (such as Daisy trying to seduce Benjamin through dance one midsummer night) and vignettes (such as Benjamin and Tilda Swinton in their own version of Lost in Translation) that are eminently engaging throughout, and yet The Curious Case of Benjamin Button ultimately seems to add up to less than the sum of its parts. (This is particularly true of the last hour, where it begins to devolve into an interminably long Abercrombie & Fitch ad.) Part of the problem is that the script starts beating its central thesis — “time keeps slipping, slipping, slipping into the future” — into the ground after awhile. But, even allowing for that, there are clumsy plot holes throughout. Ben and Daisy (well, Ben) reach a decision near the end of the film that makes zero sense from any perspective, other than to add further poignancy to their romance. Characters are created (Benjamin’s sister, Julia Ormond’s dad) that seem to have no other purpose than to drive the story along, and disappear as soon as it’s convenient.

Taking a step back from the basic plot mechanics, Button often seems confused about what it really wants to say. At times, it veers in the direction of “No fate but what we make“…ok, I’m all for free will. Later, in the middle going, it digresses in Paris for a visually arresting but totally-out-of-left-field Amelie-style reverie on the cruel vagaries of luck. (Which seems clever, until you realize that the entire sequence makes no sense given that we’re meant to have been reading from Button’s diary the whole time.) But if free will and/or randomness is the order of the day, then why do Ben and Daisy seem to keep circling each other all their lives (and why do so many second-tier characters seem to hold down the same jobs their parents did?) Is it…fate? I wasn’t expecting Button to come up with a unified theory of the universe or anything — Life sure doesn’t have one that I’m yet aware of. (Ok, other than “life is a box of chocolates,” etc. etc.) But the movie is so emphatic and precise about the short term points it’s making that, taken as whole, it all seems a bit poorly thought through.

Now, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button isn’t a disaster by any means. In fact, it’s one of the most sumptuously filmed movies I’ve seen this year. Still, as I walked out of the theater — and even more in the days since — I found the film wanting. At first, I assumed the problem was Fincher, who’s a quality director (Zodiac, Fight Club) but whose style might’ve been too cool, clinical, and remote for this particular project. But, the more I think about it, it was probably Fincher’s distance and reserve that prevented Button from becoming an unwatchable schmaltzfest. (Roth seems the real culprit.) In any case, Benjamin Button is a likable lad who shows occasional flashes of real potential. But, other than that whole aging-young thing, he unfortunately doesn’t end up seeming all that special.