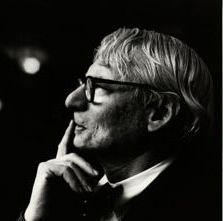

So, with the first slew of summer tentpole movies still over a week away (and, aside from Troy and possibly Spidey 2 and Azkhaban, it looks like a remarkably poor crop this year…Exhibit A: Van Helsing), I went over to check out My Architect: A Sons’ Journey at the Lincoln Cinemas last night. The documentary follows writer-director Nathaniel Kahn’s attempt to understand and come to terms with the life and work of his deceased prodigal father, Louis Kahn, who, besides being one of the more renowned architects of the postwar period, also kept up three different families and died anonymously and deeply in debt in a Penn Station bathroom in 1974. Mostly haunting, occasionally saccharine, My Architect succeeds inasmuch as it explores the mysteries of the father, but fails whenever it wallows in the emotional insecurities of the son.

So, with the first slew of summer tentpole movies still over a week away (and, aside from Troy and possibly Spidey 2 and Azkhaban, it looks like a remarkably poor crop this year…Exhibit A: Van Helsing), I went over to check out My Architect: A Sons’ Journey at the Lincoln Cinemas last night. The documentary follows writer-director Nathaniel Kahn’s attempt to understand and come to terms with the life and work of his deceased prodigal father, Louis Kahn, who, besides being one of the more renowned architects of the postwar period, also kept up three different families and died anonymously and deeply in debt in a Penn Station bathroom in 1974. Mostly haunting, occasionally saccharine, My Architect succeeds inasmuch as it explores the mysteries of the father, but fails whenever it wallows in the emotional insecurities of the son.

The advertising copy for My Architect quotes a New York Magazine review deeming it a “Citizen Kane-like meditation,” and at its best moments the film does suggest comparison with that 1941 classic. Inveterate romantic, spiritual nomad, ill-tempered workaholic, and a scarred and often-anxious thinker obsessed with issues of permanence and legacy, Louis I. Kahn is a man of many, many layers, and much of the resonance of My Architect comes from seeing his friends, admirers, lovers, and enemies grapple with their still-powerful memories of him, twenty-five years after his death. The film might have benefited from a more dispassionate analysis of Kahn’s work — certainly not all of his buildings are masterpieces (the film does say as much about a U-Penn medical complex), and I thought his plans for redesigning downtown Philadelphia were particularly ill-conceived. (I’m all for reducing automobile traffic in urban areas, but it seems strange and off-kilter to commemorate the cradle of the republic with the type of primitivist ziggurat Kahn seemed to specialize in.) Still, one can hardly fault Kahn for erring on the side of eulogy when remembering his father in film.

What one can fault Kahn for, however, is the amount of time spent in My Architect on his own personal Oprah-esque mission of emotional acceptance. Particularly in the second hour, the movie takes long detours away from the architect’s portfolio to examine Nate’s relationship with his half-sisters or his cloudy memories of his dad’s hands. And, while I’m sure this is all very important to Nate Kahn, it’s frankly not very interesting to the viewer. In fact, I thought after a while that Kahn’s persistent presence — perhaps even mooning — in every interview or location detracted from our understanding and appreciation of his subject. For example, it’s hard to contemplate how Louis Kahn’s failure to build a synagogue in Jerusalem may have impacted the man when we have to sit through Nate cutely dropping his yarmulke over and over again.

What one can fault Kahn for, however, is the amount of time spent in My Architect on his own personal Oprah-esque mission of emotional acceptance. Particularly in the second hour, the movie takes long detours away from the architect’s portfolio to examine Nate’s relationship with his half-sisters or his cloudy memories of his dad’s hands. And, while I’m sure this is all very important to Nate Kahn, it’s frankly not very interesting to the viewer. In fact, I thought after a while that Kahn’s persistent presence — perhaps even mooning — in every interview or location detracted from our understanding and appreciation of his subject. For example, it’s hard to contemplate how Louis Kahn’s failure to build a synagogue in Jerusalem may have impacted the man when we have to sit through Nate cutely dropping his yarmulke over and over again.

Still, to be fair, this gripe, while a significant one, doesn’t kill the movie by any means. If it comes to your town, My Architect is well worth seeing as a study of one man’s struggle to achieve some kind of permanence during and despite a transient life, and how memories, like buildings, can both last forever and fall into disrepair.